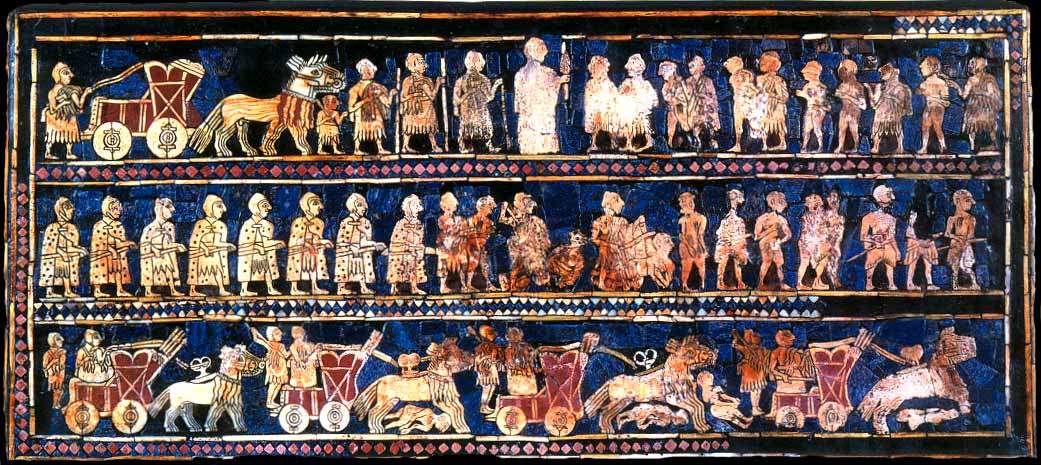

Armies battling. War horses clad in iron armor charging into battle. Soldiers firing fiery bolts from crossbows and burning towns. Gaining an empire in the ancient world required strategy, command over armies, and often brutality. But keeping an empire together was a delicate matter. Why should your subjects submit to your rule? Why couldn’t the people choose their own ruler? Ancient emperors held their peoples together with threats; offers of protection, jobs, and treasure; and the promise of divine intervention. But there’s one thing every empire in history had in common: They all fell apart in the end.

If you look at the map of the world today, you’ll see over 190 nations, all with clearly defined borders. Italy, for example, is on the edge of the Mediterranean Sea, and it is shaped like a boot. It all seems neat, tidy and squared away. But even in the last 20 years, there have been changes, with borders redrawn and over 30 new countries created. Throughout the entire course of human history, there have been huge shifts in power, cultural changes, dramatic invasions, and borders redrawn over and over.

So how did people go from being hunter/gatherers 15,000 years ago to living in towns, forming governments, and building armies bent on takeover? Actually, it all started with farming. When people discovered how to grow their own food, they began living in permanent settlements. Sounds harmless, right? Well, since farming meant there could be more then enough food for everyone, some people started doing other things, like making pottery and jewelry. And they would trade what they made for food. So far, so good. But other people started arguing over resources, like who should get the best land for growing crops or access to the local well or water supply.

With bigger populations fighting over land and resources, leaders emerged to help settle disputes. Some leaders worked through problems peacefully. Others fueled the flames and rallied groups to choose sides—and they strategized to gain more wealth for themselves. Families and individuals could grow in power to the point that they could declare themselves kings. The most ambitious—and some might say ruthless—kings raised armies and invaded other territories. They wanted to dominate the world. They wanted to have it all.

Living under an ancient empire had some pluses, though. Yes, you had to live under the empire’s rules and pay taxes of tribute. But sometimes ancient empires really did provide long-term protection from invasions by other (and maybe worse) people. Ancient empires also spread ideas and culture to new places, and when there were periods of peace, empires could help the arts and sciences flourish.

Glorious and great. Bad and blood-drenched. Ancient empires changed the world.

Egypt

Mysterious hieroglyphics. Abandoned tombs filled with mummies and golden artifacts. Great pyramids surrounded by desert sands. Ancient Egypt rose to power in 3200 BC, combining the farming settlements along the Nile River to create the first Egyptian kingdom. The fortunes of the people were deeply dependent on the Nile River—growing their food in the rich black soil along the river’s edge.

The religion of the ancient Egyptians reflects their reliance on the natural world. The Sun god, Ra, was the most powerful of all the gods. But there were dozens of others. The lion-headed Sakhmet was the goddess of fire and vengeance. Horus, the falcon, was the god of the sky and war.

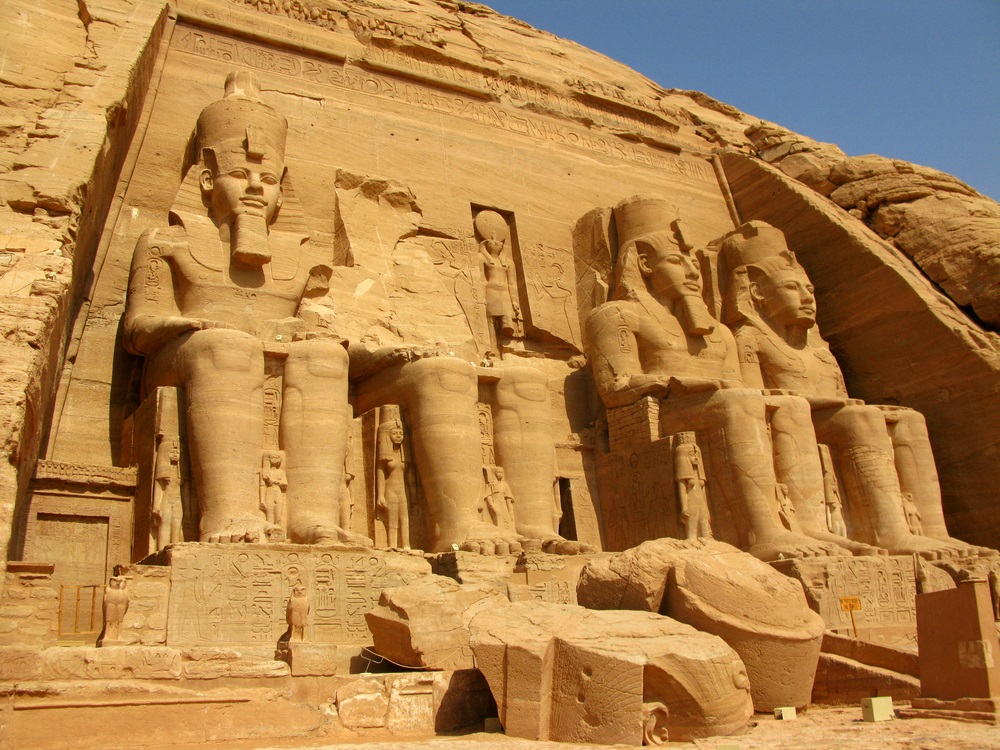

The kings and queens, called “pharaohs,” were considered gods on Earth, and it was their job to make sure the kingdom was in harmony with all the gods. That meant having religious ceremonies and building temples to honor the gods. For example, there were temples all around Egypt filled with live crocodiles to honor the god of the Nile, the crocodile-headed Sobek.

Maintaining harmony with the gods also meant that when a pharaoh died, he or she had to be ushered into the afterlife. Elaborate tombs were built for the pharaohs, their bodies were mummified to preserve them, and they were buried with many of their possessions, which it was believed they would need in the afterlife.

Ancient Egyptian culture lasted for almost 3,000 years, but the Egyptian Empire reached its peak in the “New Kingdom,” which lasted from 1550 to 1069 BC. During this period, Egypt expanded its territory, pushing into the Kingdom of Kush in Ethiopia and battling the Hittites, a neighboring empire to the north. Before the New Kingdom, the Egyptian Empire had been somewhat weakened, with some of its outer territories given up to rival kings. The pharaohs of the New Kingdom were determined to reestablish Egypt’s full power—and they engaged in many battles with surrounding forces.

One of the most epic battles was the Battle of Kadesh, when pharaoh Ramesses II invaded Hittite-held territory with his massive army of foot soldiers and thousands of horse-drawn war chariots. Although the battle was a draw, it sent the message that the Egyptians were as strong as ever, and the border wars continued until 1258 BC when Ramesses II signed a peace treaty with the Hittites. A copy of this treaty, written in hieroglyphs on the walls of Ramesses II’s tomb and on clay tablets, survives today, the oldest surviving international peace agreement in history.

Maintaining the Egyptian Empire was far from easy, especially when members of the royal family squabbled among themselves and jockeyed for power. In the end, droughts, famine, foreign invasions, and the high costs of war finally caught up to the ancient Egyptians. After five centuries, the pharaohs could no longer hold their empire together and it broke up into a series of smaller kingdoms, some ruled by foreign invaders.

Archaemenid Empire

At a time when the world’s population numbered about 110 million, 50 million—almost half of all the people on the globe—lived within the Archaemenid Empire, also known as the First Persian Empire. Never before or since has one empire commanded such a large portion of the world’s peoples. At its peak, the empire reached from Egypt across the Middle East and Mesopotamia all the way to Punjabi in modern-day India.

The founder of the empire was Cyrus the Great. In 550 BC, he took over the Median Empire in the heart of the Middle East and began expanding his territory by building a powerful army and conquering neighboring kingdoms. His successors continued building the empire, and its fourth king, Darius the Great, built a grand new capital in 518 BC at Persepolis, located in modern-day Iran.

The rulers of the empire followed the religion of Zoroastrianism. Darius the Great and his son Xerxes believed that the god Ahura Mazda created the universe. They also believed that there are many powerful good spirits in the world, but that there are also demons and that people must fight against the evil these demons bring. An inscription over the gate to Persepolis read, “A great God is Ahura Mazda, who created this earth, who created yonder sky, who created man, who created happiness for man, who made Xerxes king… King of Kings, King of countries containing many kinds…”

This idea that the empire contained “many kinds” of people was central to its success. When the palaces at Persepolis were built, artists and craftspeople from all corners of the empire were brought to work on the project. This led to a mixing of cultures and styles.

The empire was also generally well-run and efficient. A Royal Road was built that stretched 1,500 miles across the realm, which traders, tax collectors, and messengers could use. Taxes were collected in the form of grain from Egypt, silver from wealthy Babylonia, and gold dust from India. Although the emperors demanded taxes and tribute, they did not impose their religion or culture on other ethnic groups.

The Persian Empire was enormously rich. In Persepolis, there was a treasury, with over 1,000 employees who counted and polished gold and silver. They also kept records of all kinds of payments and transactions. Their records were mostly written in the Elamite language, with cuneiform script pressed into clay tablets.

Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great was the young king of Macedonia, an independent state in between the Greek and Persian worlds. Although Macedonia had been briefly aligned with the Archaemenid Empire, it was strongly influenced by Greece.

When Alexander was a boy, his father (King Philip II of Macedonia) hired the famous Greek philosopher Aristotle to be Alexander’s tutor. From Aristotle, Alexander grew to be very pro-Greek, but he also learned much about the culture and manners of the Persian world.

Neighboring Greece was an influential culture of city-states, and it was a profoundly creative society. The Greeks essentially invented literature. Homer wrote The Odyssey and The Illiad, two epic tales that are still considered super classics today. And the Greek playwright Aeschylus thought up the idea of writing plays with characters that talked to each other—and they were the first dramas ever. The Greeks also made major advances in math, science, art, and architecture. Instead of looking outward toward conquest, the Greeks were more focused on their internal affairs and the idea of democracy—the participation of all citizens in self-government.

The Achaemenid Empire had repeatedly tried to invade and take over Greece. But Greece had fought them off every time. Unfortunately, the Greek city-states were often at war among themselves. And Alexander’s father, Philip II, took advantage of those squabbles.

Philip II had great plans to expand his territory. He took an army into Greece and pressured the Greek city-states to form an alliance with him called the League of Corinth. According to their agreement, none of the members of the league would go to war against each other. Next, Philip planned to take his armies into the Archaemenid Empire and to bring it down. However, before he got to put his plan into action, he was assassinated by one of his own bodyguards. No one knows exactly what caused the bodyguard to turn against Philip. But the result was that Alexander took over the throne at the age of 20.

Over an 11-year period, Alexander led armies across the entire Archaemenid Empire, conquering all of the Middle East, including Egypt, and then went on through Persia. He ultimately ruled over an area covering more than 2 million square miles. Although he was often outnumbered by better-armed Persian forces, he demonstrated brilliant strategy and charismatic leadership, and he was not once defeated in battle. He founded dozens of cities, and he spread the Greek language and culture far and wide. At the same time, he respected and sometimes adopted Persian and other foreign customs, which made ruling over such diverse areas much easier.

In an era when thousands of different gods were worshipped by hundreds of different cultures, Alexander claimed to be a descendant of Greek heroes, who were half-mortal and half-immortal. In Egypt, he was named pharaoh, the son of Ra, the god of the Sun. At home, he was declared the son of Zeus, the most powerful god in the Greek pantheon.

Alexander sometimes displayed the wrath of an ancient god. When he and his army invaded Persepolis, the Archaemenid capital in 330 BC, they burned it to the ground. They also looted its treasury. It is said that Alexander took away all of Persepolis’s gold and silver on thousands of camels and other pack animals. All these riches paid for a tremendous revival of Greek art and architecture throughout what is known as the Hellenistic Empire.

Although he had become tremendously powerful, Alexander was not invincible. While preparing to take his armies home by sea from Babylon, he grew sick with fever and died suddenly at the age of 33. One of his generals carried his body back to Egypt, where he was buried alongside the tombs of the ancient pharaohs.

China, Qin and Han Dynasties

Five thousand miles away from the center of the Greek world, another empire was brewing. The Chinese people had formed their first unified kingdom in about 2000 BC along the banks of the Yellow River. But as in the rest of the world, holding things together wasn’t easy.

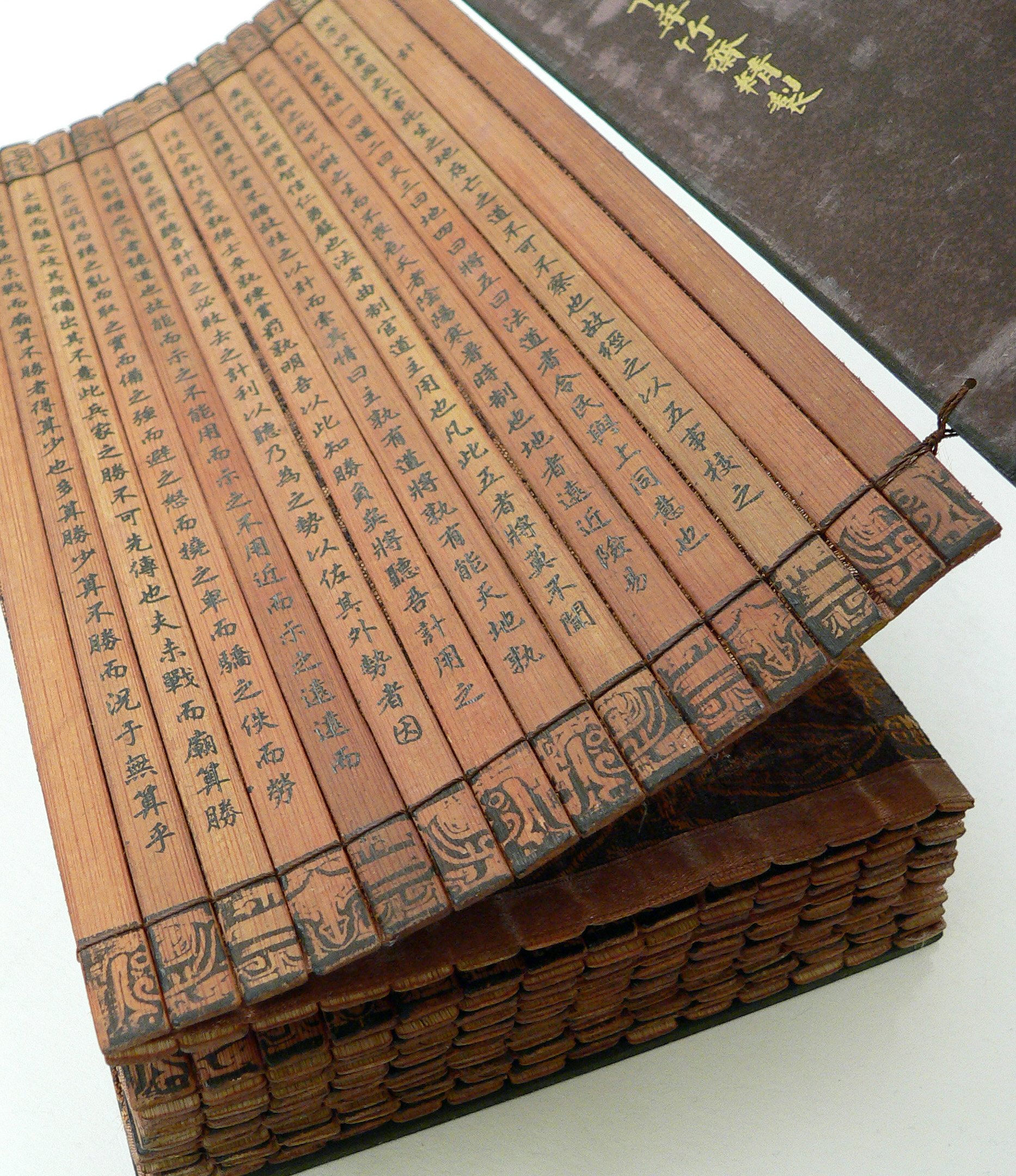

By about 400 BC, China was divided into seven kingdoms that were frequently at war. One of the most popular texts of that period was “The Art of War,” which is still considered a masterpiece by military strategists today. “The Art of War” doesn’t just give advice about how to win battles; it gives advice about how to end wars. The leaders of the kingdom of Qin, which had a powerful army and some of the most modern weapons of the age, used these strategies to take over all of the warring states and begin China’s first Imperial Dynasty, known as the Qin Dynasty.

The emperor of the Qin Dynasty, Qin Shi Huang, ruled supreme over a unified China. He built roads to increase trade, and he started construction on the Great Wall of China to protect against raids from the north. But he was also a tyrant. He had books burned when they contained ideas that he disagreed with. When scholars disagreed with him, he literally had them buried alive. Life was harsh for the people in the Qin Dynasty and they resented the emperor’s total crack-down style of ruling—and for those reasons, this dynasty didn’t last long.

The rebel leader Liu Bang led a successful revolt against the Qin Dynasty in 209 BC, and he became the first emperor of the Han Dynasty, which lasted for 400 years. Although many wars were fought over territory during the Han Dynasty, China remained largely unified during this period and made several cultural advances.

One of these advances was international commerce: During the Han Dynasty, a royal diplomat named Zhang Qian was sent to explore the unknown regions west of China and to open trade and communication if he could. Zhang Qian’s travels led to the creation of what is called the Silk Road—which led all the way to the Mediterranean and allowed Greece and Rome to trade with China for the first time in history.

Another innovation was papermaking. During the Han Dynasty, a court official named Cai Lun invented modern paper out of tree bark, plant fiber, old rags, and fishnets. As weird as that recipe sounds, it made making paper cheap, and the result was easier to write on than older materials, such as silk, papyrus, and dried animal skins. His method made preserving and passing on information much easier. It revolutionized communication in China and was eventually adopted in the west.

Julius Caesar and the Rise of the Roman Empire

Far to the west of China, yet another superpower was growing. At the time of Alexander the Great, Rome had not been important enough for Alexander to even consider taking over. But the Romans were impressed, fascinated, and influenced by Greek culture—and they deeply admired Alexander and his conquests. They wanted the empire and glory that Alexander had achieved.

When Julius Caesar was born in 100 BC, Rome was a republic. It was ruled by senators who were elected by the citizens of Rome. The senators argued, made speeches, passed new laws, and picked military leaders when Rome was at war with its neighbors. Having a representative government was very unusual at that time in history. But the system was far from perfect. Lots of people—women and slaves—didn’t have the right to vote or become senators. And some of Rome’s laws seem extreme by today’s standards. For example, if you lied in court, the punishment was being hurled off a cliff to your death. Plus, the government had become corrupt. Laws were not applied fairly and taxes varied, depending on whether or not you were friends with the tax collector.

Julius Caesar was no ordinary Roman citizen. He was a powerful general and politician who greatly expanded Rome’s territory. With an army of 50,000 Roman soldiers in 52 BC, he took over and subdued Gaul (modern-day France and Belgium). Caesar turned thousands of prisoners of war into slaves. And he paraded Gaul’s defeated leader through the streets of Rome, where he was executed.

In Rome, some of the senators thought Caesar was getting too powerful—and they tried to reduce his influence. In response, Caesar marched his army through the streets of Rome and got himself declared temporary dictator, the supreme ruler of Rome. He then chased his chief opponent all the way to Egypt. There, when he wasn’t engaged in street battles, Caesar fell in love with Cleopatra.

When Caesar got back to Rome, he gave the right of citizenship to more people, pardoned many of his former enemies, made the tax laws fairer, and started a public building program. Although his dictatorship was supposed to be temporary, some senators thought he was going to declare himself king and maybe even try to have Caesarion, his son by Cleopatra, named as his successor. Caesar’s enemies plotted his murder. They lured him to a back room of the senate building to “sign some papers.” On March 15 in 44 BC, Caesar was assassinated. It’s said he was stabbed 23 times.

Following Caesar’s death, there was a huge struggle for power in the Roman republic. In the end, the senate declared Caesar’s adopted son Octavius to be the leader of Rome—for life. He was given the title Caesar Augustus, and he became the first Roman emperor.

At its peak, Rome ruled the lands all around the Mediterranean Sea, plus what later became England. The Roman emperors launched massive construction projects, building roads throughout their empire, aqueducts for carrying water to cities, and amphitheaters and stadiums where the public could watch plays and sports.

Of course, the fears of the senate about having a king or emperor in charge were justified. Some of Rome’s rulers were brilliant and quite fair. Others were tyrants and basically nuts. Nearly unlimited power allowed Rome’s emperors to do both great and terrible things.

Rome ruled supreme for hundreds of years, but like other empires before and after, its grip on power eventually weakened. The last Roman emperor was forced into early retirement in AD 476.

Maya

Far across the Atlantic Ocean, another empire rose and fell—without ever being known to China or Rome.

Isolated from the rest of the world, the Maya civilization included hundreds of cities in what is now modern-day Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, and Belize. With roots going back as far as 2000 BC, Maya society reached its peak between AD 200 and AD 900. Many once-great Maya communities now lie buried beneath rain forest and jungle. The ruins of these power centers tell the story of Maya kingdoms, wars, and struggles for dominance.

Blocky symbols carved in stone cover ancient Maya temples and stone pillars called “stelae.” Researchers have long understood how the Maya wrote down numbers and created a sophisticated calendar based on their observations of the stars. But the Maya’s written language was almost a total mystery until about 30 years ago. Amazingly, a 15-year-old named David Stuart helped to crack the secret of the Maya’s ancient language—and soon details about the Maya’s royal intrigues and power shifts were revealed.

The great Maya city of Tikal was almost constantly at war with its neighbors during the beginning of the Maya period. But Maya glyphs tell of a warrior named Fire Is Born who came from the west with an army in AD 378 to conquer Tikal and dominate the entire region. Fire Is Born’s arrival did more than unify the Maya city-states; it ushered in a period of intense trade and an explosion of architecture and artistry.

Under Fire Is Born, Tikal became a superpower, taking over numerous previously independent city-states, executing their rulers, and putting underlords from Tikal in charge. For 100 years, Tikal was unrivaled, but in the 5th century, the nearby city-state of Calakmul began to challenge Tikal. Soon it was the leaders of Calakmul—the Kan Dynasty (aka the Snake Dynasty)—who began to dominate.

But in the end, all of the Maya kingdoms and all their large cities disappeared back into the jungle. Some were destroyed by civil war and others were just abandoned. No one knows exactly why. It may be that the Maya population became too large and that famine led to a loss of belief in the Maya leaders and their rituals. And it may be that we will never know the exact cause.

Written by Margaret Mittelbach

[wp-simple-survey-28]