Mapping Migration

As autumn is upon us, the annual avian fall migration is well under way for birds that use North American flyways to move from northern summering grounds to southern wintering areas. Geese fly overhead in V formations as they move south and colorful migrating warblers stop in local parks to rest up before continuing their journeys. This massive movement of birds brings with it an opportunity to learn about the biology and geography of migration, with a bit of mathematics thrown in for good measure. But before learning about these elements of migration, it is a good idea to discuss why birds undertake this expedition in the first place, and how they are able to accomplish the feat.

Motives for Migration

Most birds and other animals migrate for one or more of three basic reasons.

First, animals may be looking for food. They may have depleted the resources in a particular area, or they may be trying to keep up with the changing patterns of available vegetation. The latter reason is what has wildebeest and zebras trotting around the Serengeti each year. They follow rainfall patterns in order to find fresh and ample vegetation.

Second, animals may migrate to escape extreme seasonal temperatures. Many birds, for example, fly south to warmer climates for the winter, while other animals travel to get to special seasonal shelters. For instance, little brown bats fly 200 to 800 kilometers between their outdoor summer roosts and their winter cave roosts. The caves provide safe, sheltered places for them to hibernate during the cold months.

Third, animals migrate to get to their breeding grounds. Salmon, for instance, swim from their ocean abode to the exact area of the river or stream where they were born, so they can spawn there before they die.

Navigation

Now that you more fully understand the reasons behind these seasonal journeys, it’s also important to think about how birds and other animals migrate. How do they know where to go and what route to take?

Animals find their way over vast distances in an impressive number of ways. Many animals use visual landmarks to help them move from one place to another. Elephants, for instance, migrate largely by sight. The oldest female elephant, or matriarch, has learned to use fixed landmarks such as rivers and mountain ranges to lead the other members of the herd to food, water, and safety. Some animals rely more on their sense of smell to figure out where they are going.

Other animals, including birds, use the position of the sun as a compass to help them navigate over long distances. But what about birds, such as waterfowl, which migrate at night? Many of them look to the stars for guidance.

Several animal species are even able to use the Earth’s magnetic field as a guide. Bats and sea turtles, for instance, likely use small particles of the magnetic mineral called magnetite to orient themselves along magnetic pathways.

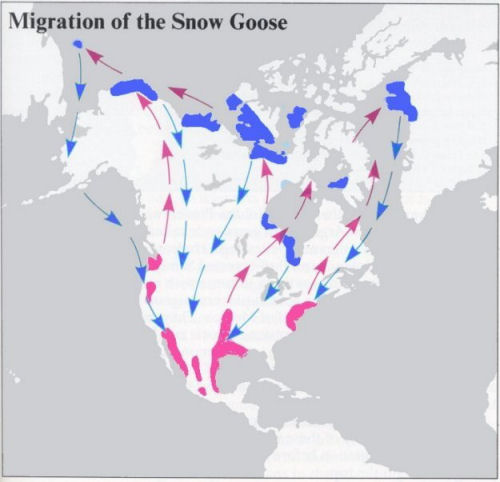

Migration Maps

Studying the seasonal flight paths of a few common migrating birds (and observing the world map alongside these paths) helps us to gain knowledge about the geographical relationships between countries. Some useful maps of bird migrations can be found here.

Below are a few species to get you started in your exploration of the geography of migrations.

Humpback Whales

Humpback whales travel between their summer feeding grounds in the North Pacific and their winter breeding grounds off Hawaii, Okinawa, and Central America. They travel further than any other mammal during migration—up to 8,500 kilometers each way. Use this map to track humpback whale migration:

http://www.ukogorter.com/portfolio/maps-misc/map-humpback-migration.html

Monarch Butterflies

Monarchs are the only butterflies to make a long two-way migration each year. But the same insects don’t complete the round trip. Instead, one generation of monarchs flies south to central Mexico for the winter. On the way back up north, the monarchs stop along the way and lay eggs. Then the newborn monarchs continue the flight north. This egg-laying transition happens at least once more on the flight north. Use this map to track monarch migration:

http://www.monarchwatch.org/tagmig/fallmap.htm

Wildebeest/Zebra

Wildebeest and zebras, along with fewer numbers of gazelles, migrate throughout the year in a circular pattern through Tanzania and into Kenya, then back again. They move to find fresh grasses to graze, and fresh water supplies. Follow this moving map to watch the Serengeti migration (http://www.expertafrica.com/tanzania/info/serengeti-wildebeest-migration) and use this still map to model the migration: http://psugeo.org/Africa/African%20UNEP%20Atlas/mara-serengeti-migration.jpg

Salmon

After a lifetime at sea, Pacific salmon find the same rivers where they entered the ocean, fight against the current up into smaller streams to the exact locations of their birth, and then spawn before dying. The ones that make the journey have had quite a migration. Only one in a thousand of these fish make it home again. Use this map to track the migration habits of five species of salmon in the Pacific Ocean: http://www.goldseal.ca/wildsalmon/salmon_migration.asp?pattern=summary

Fast Facts

* Monarch butterflies travel up to 4,750 kilometers during their fall migration. That is further than any other insect is known to go.

* The longest recorded water migration was completed by a leatherback turtle, which swam 20,558 kilometers in 647 days.

* Bar-headed geese migrate at 9,000 meters above the ground. That is only 1,500 meters below the average flying height of a 747 passenger plane!

Additional Resources

http://pbskids.org/catinthehat/games/migration-adventure.html – In this simple game, help the Cat in the Hat follow a purple martin on its migration south for the winter.

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/life/mammals/migration/index.html – London’s Natural History Museum provides information about animal migration

http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/studying/migration/range_maps – Here are a few examples of bird range maps, showing migration patterns.

http://www.monarchwatch.org/tagmig/index.htm – Information about the migration of monarch butterflies

Written by Joe Levit. [wp-simple-survey-15]