Imagine this: You’re hiking among wooded hills. Trees tower above you; plants and bushes brush your legs and arms. It’s the great outdoors at its best. Then suddenly, a change: The plants and bushes are replaced by… nothing… a hole, an opening, a hollow, a gap. You’re curious, of course, so you peer into the darkness, but you can’t see a thing.

It’s a cave. If you want to find out what—if anything—is inside, you’ll have to go spelunking. So, grab a flashlight (caves are dark), put on some warm clothes (caves can be cool), and change into your hiking boots (caves are often wet and slippery).

Millions of caves twist and turn beneath Earth’s surface. No one is certain about the exact number, but Tennessee alone has over 9,500 caves and Missouri has over 6,000.

The Making Of Caves

Most caves form in karst—an area of land usually made up of limestone or dolomite rock and containing sinkholes and underground streams. Rainwater in these areas seeps through cracks in the rock and combines with carbon dioxide to form a weak acid similar to the “bite” you taste in a soda drink.The acid eats away at the rock and forms hollowed out areas on the floor of the water table. Eventually—after several million years—the hollowed out areas join together to form a cave. If, over time, the water table gets lower, the cave stops getting larger. Then things really start to get interesting….

Other Ways Caves Form:

Sea Cave:

Lava Tube:

Acid-producing bacteria:

Drips and Drops

Even after a cave is formed, rainwater continues to seep into the ground above it. As before, the water picks up minerals from the rock. As the water drips into the cave, it may evaporate and leave mineral deposits on the ceiling. Little by little the deposits grow into icicle-shaped formations called stalactites.

At times, water droplets fall to the cave floor and leave mineral deposits there. Eventually, the deposits grow to become pillar-like formations called stalagmites. With enough time, stalactites and stalagmites may join to form floor-to-ceiling columns.

Here’s a memory trick for remembering the difference between stalactites and stalagmites: Stalactites stick “tight” to the ceiling. Stalagmites grow from the ground.

Troglo-whats???

To us, caves may seem like uncomfortable places to live, but not to your typical troglobiont. Named for the Greek words troglo (cave) and bio (life), these creatures spend some or all of their lives in caves. They may live in the cool, shaded entrance zone; the damp twilight zone, with its low light; or the dark zone, with no light at all. Let’s go in and have a look.

As we walk through the entrance zone, we see the cave’s temporary residents. These creatures come and go freely. Bats are probably the most well-known temporary residents. But they’re not the only ones. Bears hibernate here. Skunks and raccoons find shelter from the rain. Small animals like frogs, moths, and beetles also go in and out… and so do humans.

Moving deeper into the cave, we find crickets, earthworms, spiders, and other troglophiles, or cave-lovers. These critters may complete their life cycles in caves… or not. They can survive just as easily outside as inside.

That can’t be said about the next group of creatures we’ll find… after we turn on our headlamps.

Living their lives in perpetual darkness are the troglobites, or cave-dwellers. They include salamanders, shrimp, and fish. Having adapted to a life of darkness, these creatures are usually blind and often colorless. They could not survive outside the cave.

Eeeeewwwwwwww. It looks like snot. Yes, snot, that slimy mucus of the common cold. And the ceiling is dripping with it. Don’t touch! These snottites, or snotties as they are sometimes called, are the work of extremophiles—microbes that thrive in the most hostile environments.

Let’s return to an area near the cave entrance and step back in time.

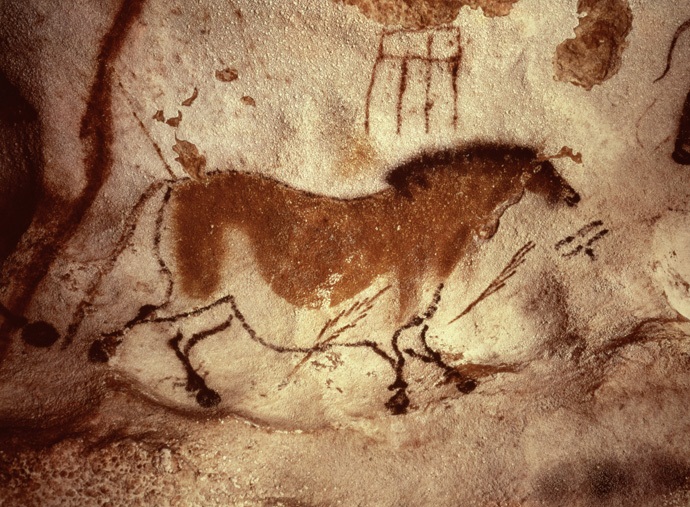

Look up. Look left and right. Look down. Perhaps you’ll see a painting created by a human being some 30,000 years ago. The image is probably a large animal—a horse, a bull, a deer, or the now-extinct woolly rhinoceros. Cave paintings exist in caves on every continent except Antarctica. But why? Were they religious art? The work of shamans? Meant to bring about a successful hunt? Used to track time? No one knows for sure.

Suppose you had lived during prehistoric times. What would you have painted on a cave wall? How would you want it to be remembered?

Written by Marjorie Frank.[wp-simple-survey-7]