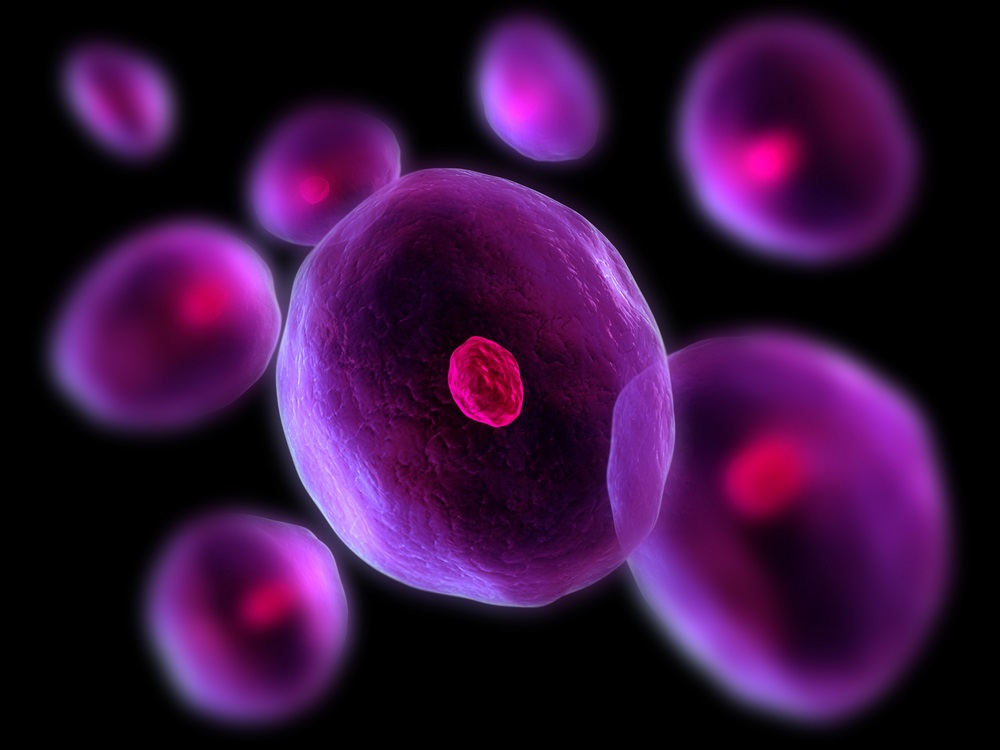

Cells are the building blocks of all life. People have cells. So do dogs, cats, spiders, and gnats. So do trees and flowers and tomatoes and blades of grass. All life-forms—all living organisms—are made from cells.

Each human body has about a 100 trillion cells. That’s 100,000,000,000,000, an almost unimaginable number. But even more mind-blowing is that each cell contains about 100 trillion atoms. Those atoms make up molecules that are constantly moving and interacting. It’s like a small city inside your cells! If you were a micronaut and were able to enter the world inside a single cell, you would be amazed by everything going on.

Cells digest food. Cells carry oxygen to your lungs. Cells fight infection and heal wounds.

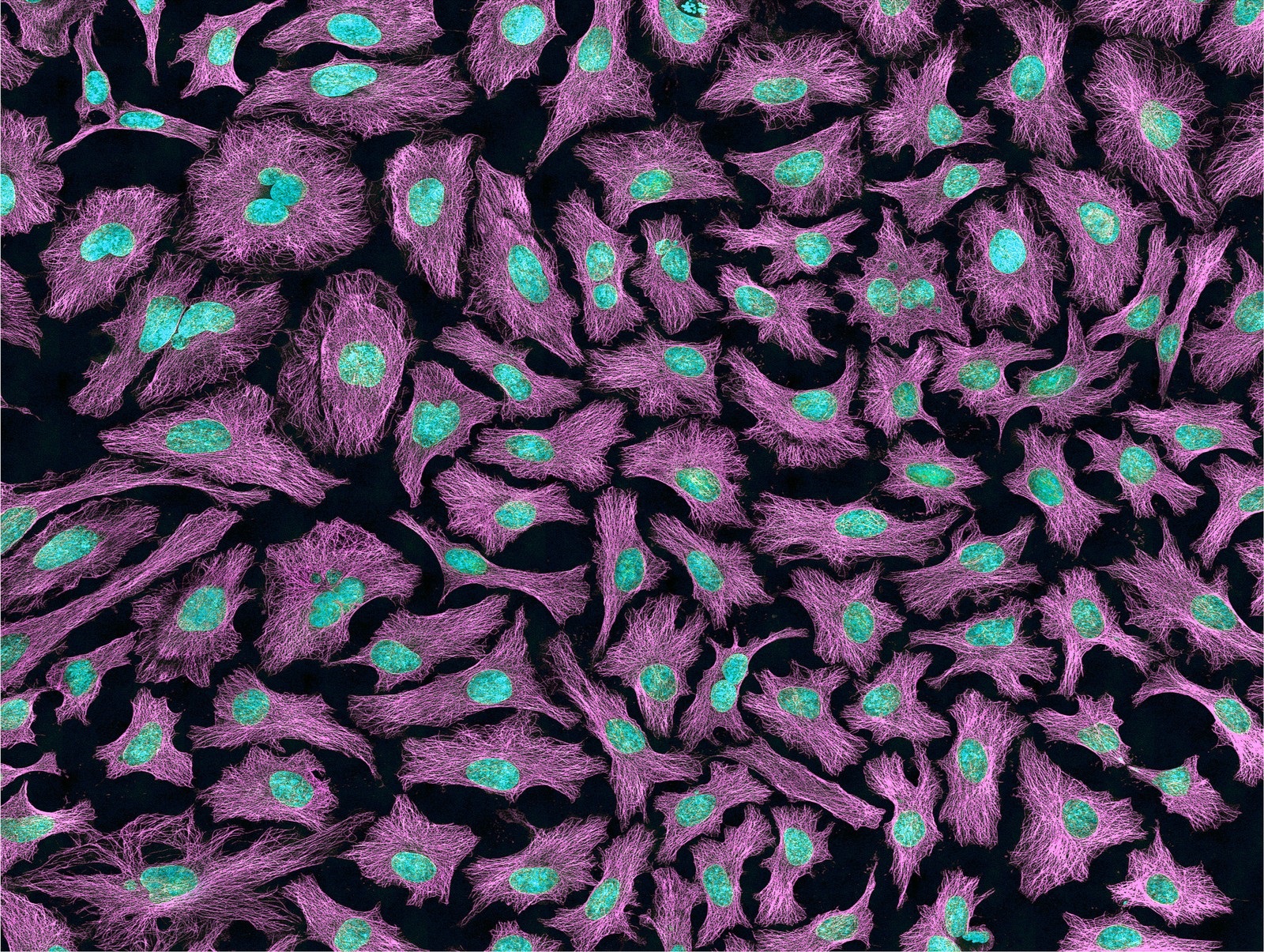

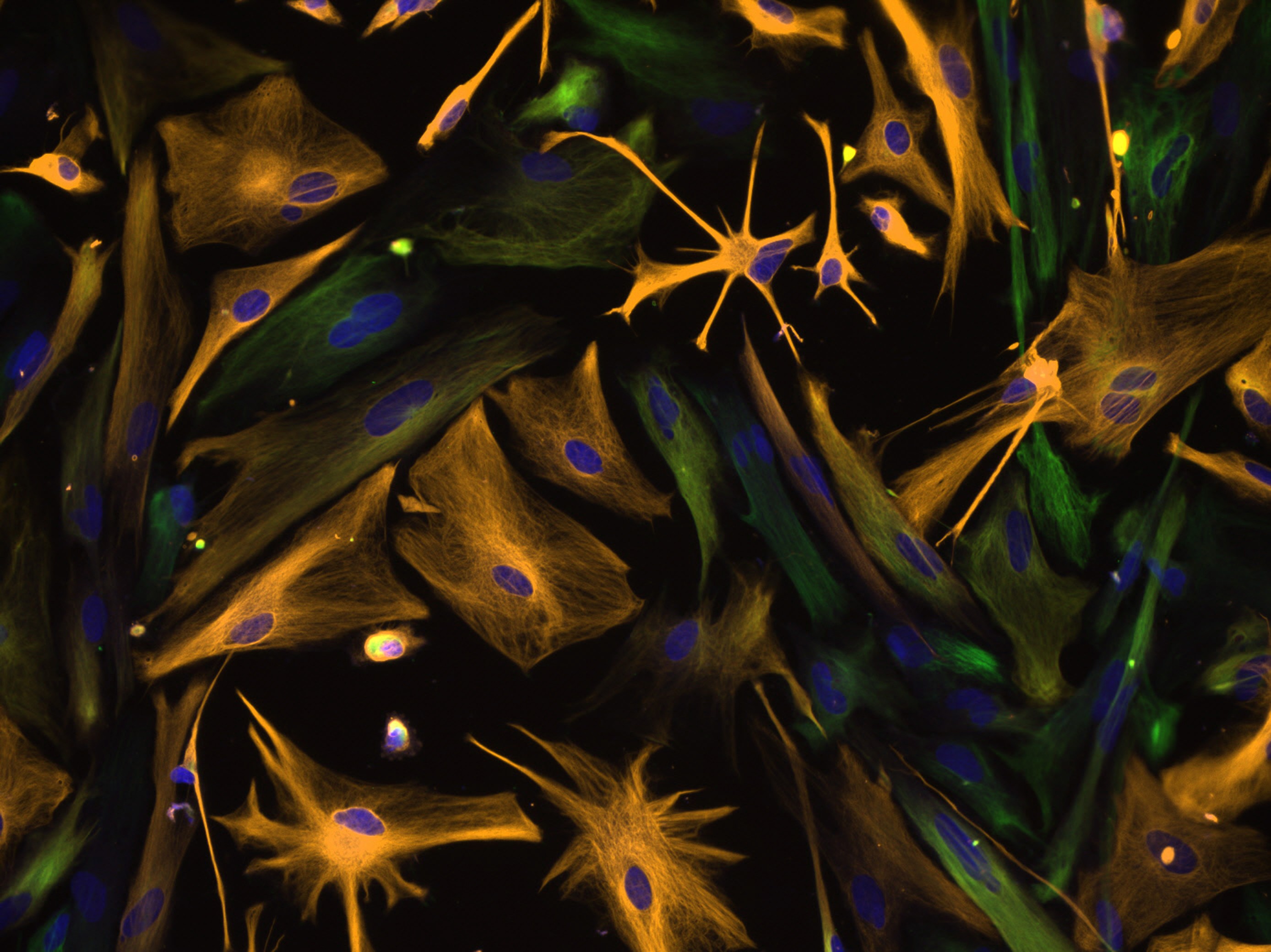

The human body has about 200 types of cells. You have red blood cells and brain cells. You even have special cells for making tears and special cells for making earwax.

Part of a cell’s job is to make exact copies of itself. Old cells die and new cells are formed all the time. Some types of cells get replaced faster than others. All your skin cells are replaced every couple of weeks. You may notice tiny flakes of skin falling off in the bath or shower. Kids lose and make about 40,000 skin cells every day.

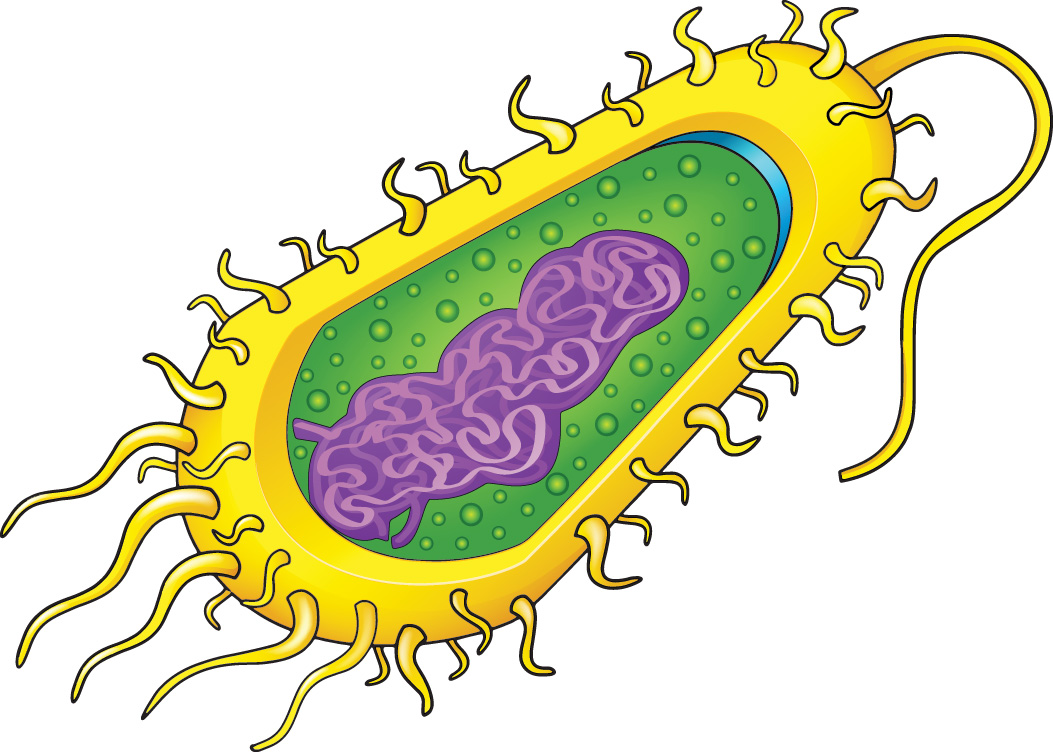

Humans are multicellular, which means we’re made of more than one cell. But LOTS of life-forms have just one cell. You might think having only a single cell would limit your options, but there are hundreds of thousands of different species of single-celled life-forms. In fact, half of all life on Earth (by weight) is made of single-celled microbes.

Almost all single-celled organisms are too small to see with the naked eye. But you can see them clearly with microscopes. The earliest forms of life on Earth were simple single-celled organisms. In fact, single-celled organisms were the only forms of life on Earth for over 1 billion years.

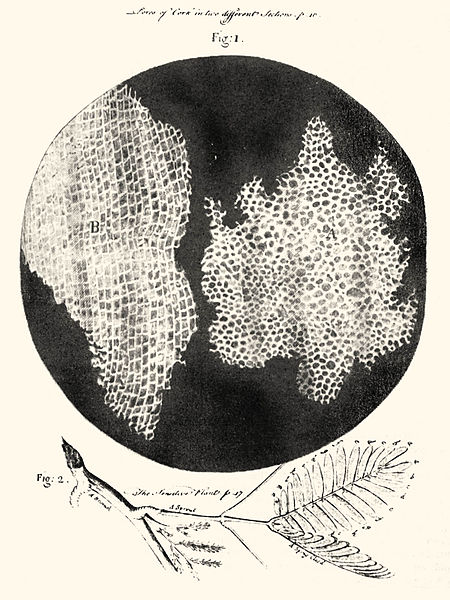

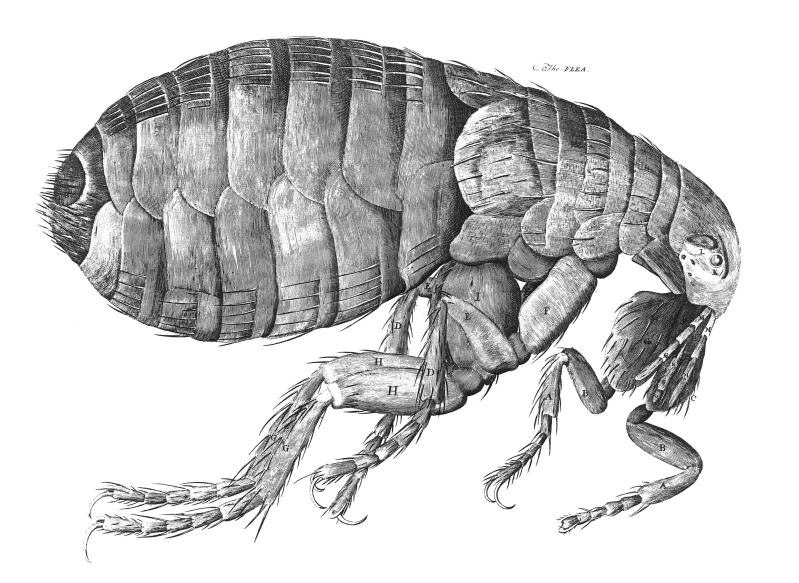

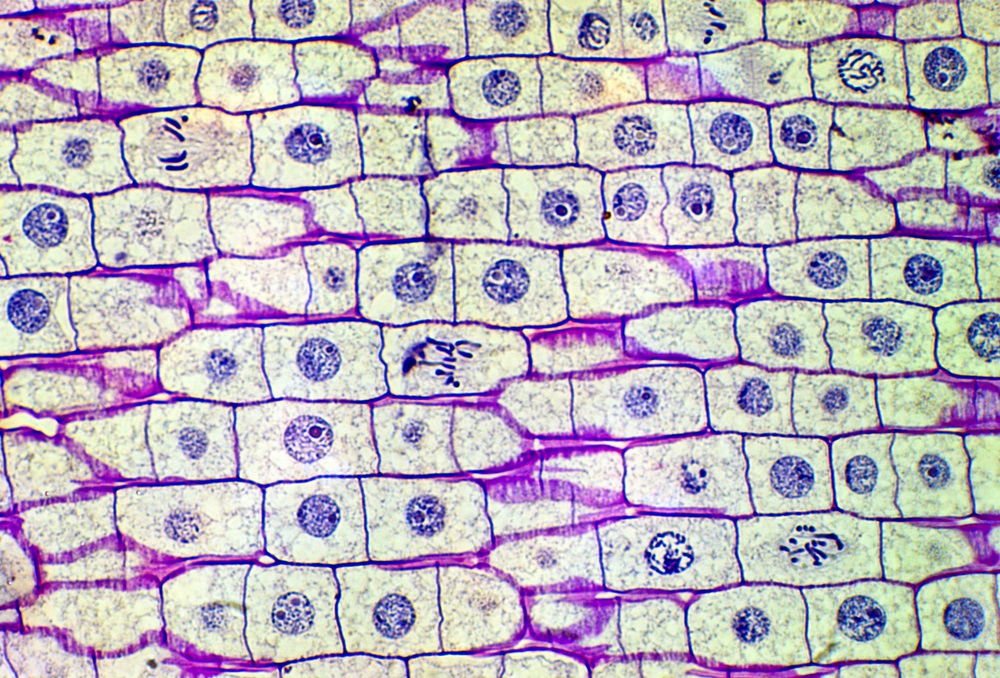

Today, we can look deep inside of cells using ultra-powerful microscopes. But there was a time when people did not know cells even existed. The first to notice them was a scientist and inventor named Robert Hooke in the 1600s. Hooke studied all kinds of things—weather, the Universe, engines—but he’s most famous for exploring the world that’s invisible to the naked eye. When he looked through his microscope at a piece of cork—which is actually part of a tree—he saw a network of what looked like tiny rooms. What he saw reminded him of cells—the little rooms that monks in a monastery live in—so that’s what he called them.

There was no photography when Robert Hooke saw plant cells through his microscope in 1665. So he drew a picture of what they looked like, and he published his work in a book called Micrographia. He wrote, “these pores, or cells . . . were indeed the first microscopical pores I ever saw, and perhaps, that were ever seen.”

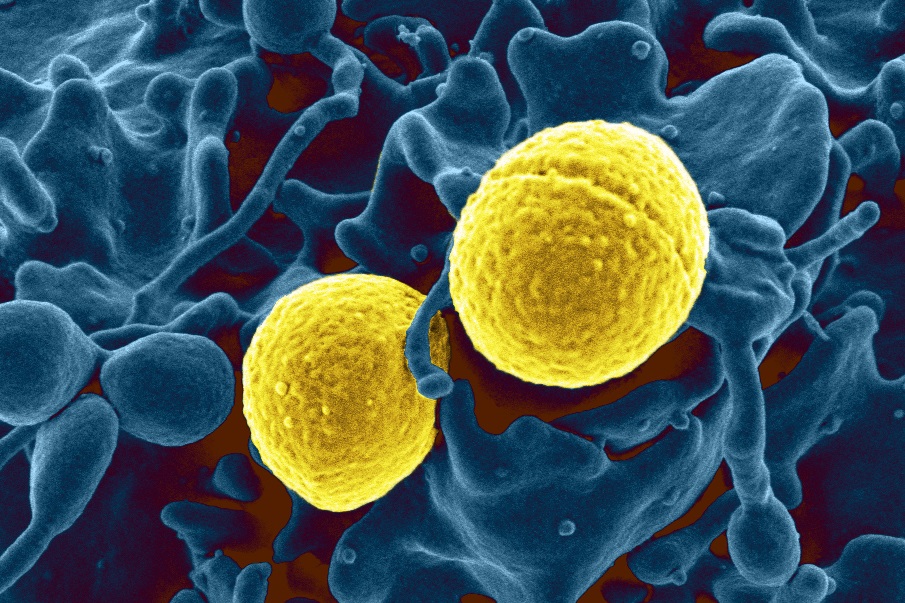

After seeing what Hooke had discovered, another scientist and inventor, Anthony van Leeuwenhoek, began making microscopes like crazy—he had as many as 500. When he took a sample of plaque from his own mouth and looked at it under one of his microscopes, he observed that “there were many very little living animalcules, very prettily a-moving.” What he called animalcules were actually bacteria—the first anyone had ever seen. The idea that there were “beasties” living inside our bodies blew people’s minds and opened the door to a huge number of discoveries.

Want to know something a little creepy and a little amazing? Every human being, in addition to human cells, has trillions of non-human cells. These non-human cells are called your microbiome. Most of the microbes in your microbiome are in your guts and they help with digesting food and keeping you healthy. Recently a large group of scientists working on the Human Microbiome Project discovered that it’s normal to have about 10,000 different species of microbes in (and on) your body. And these microbes are not just lazing around. These powerful single-celled microbes do things like make essential vitamins and fight off infections.

The cells of plants, including the ones we eat, have stiff walls around them made of a material called cellulose. People can’t digest cellulose, and any cellulose we eat passes out of our bodies in our waste. Cellulose is actually a type of sugar that has energy in it. To digest the cellulose and get its energy, many animals rely on their own unique microbiomes. Lots of plant-eating (and wood-eating) species—from cows to koalas to termites—have special bacteria in their guts that can break down cellulose. Without these bacteria, these vegetarian creatures would go hungry.

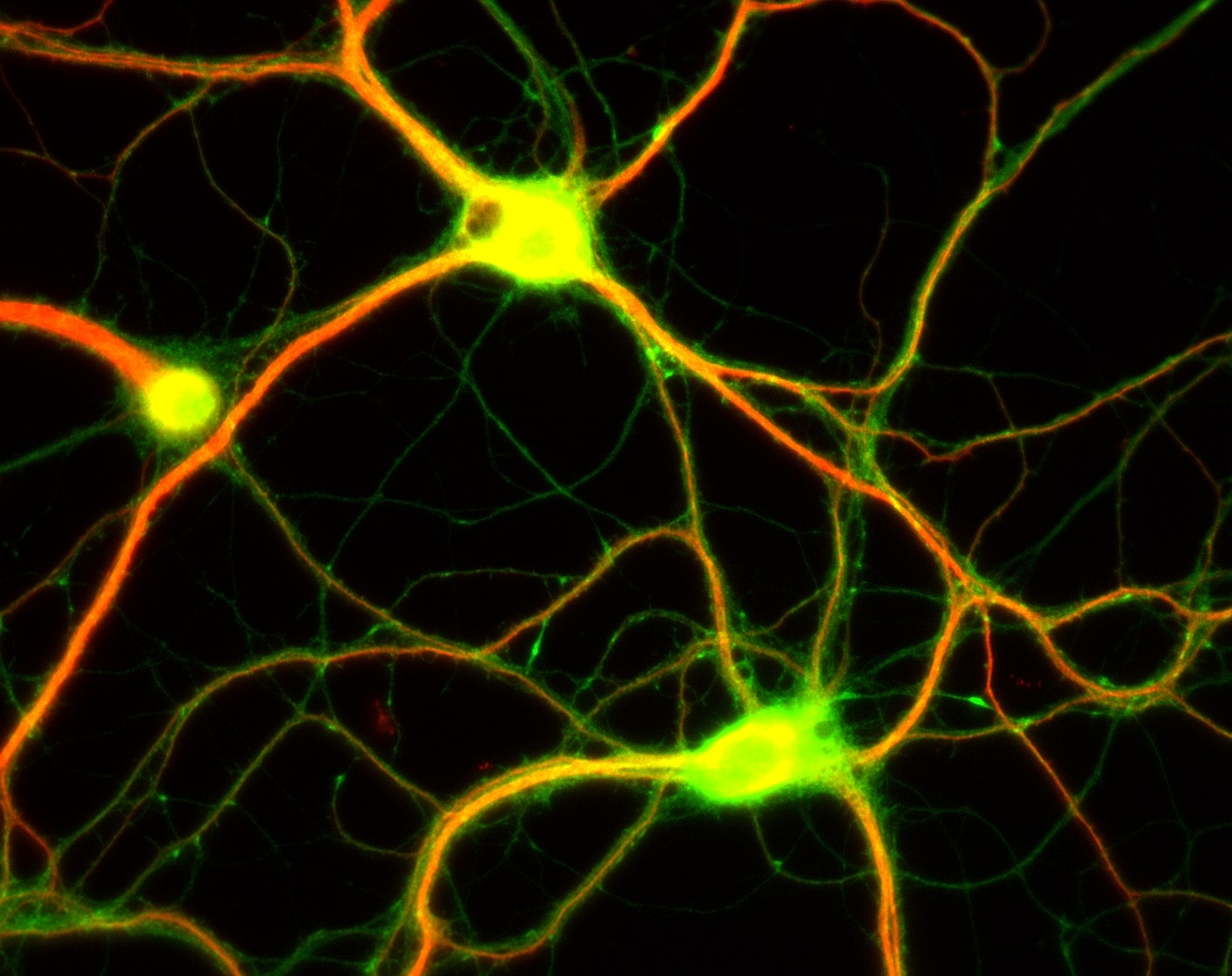

Cells are involved in so many aspects of our lives that they really make you think. But sometimes—well, always— cells are the ones doing the thinking. Your brain and the brains of everyone you know, including your cat and your goldfish, are made of cells. Brain cells and the other cells in your nervous system are called neurons and they are highly networked. You learn and remember things because your brain cells are making and strengthening connections with each other.

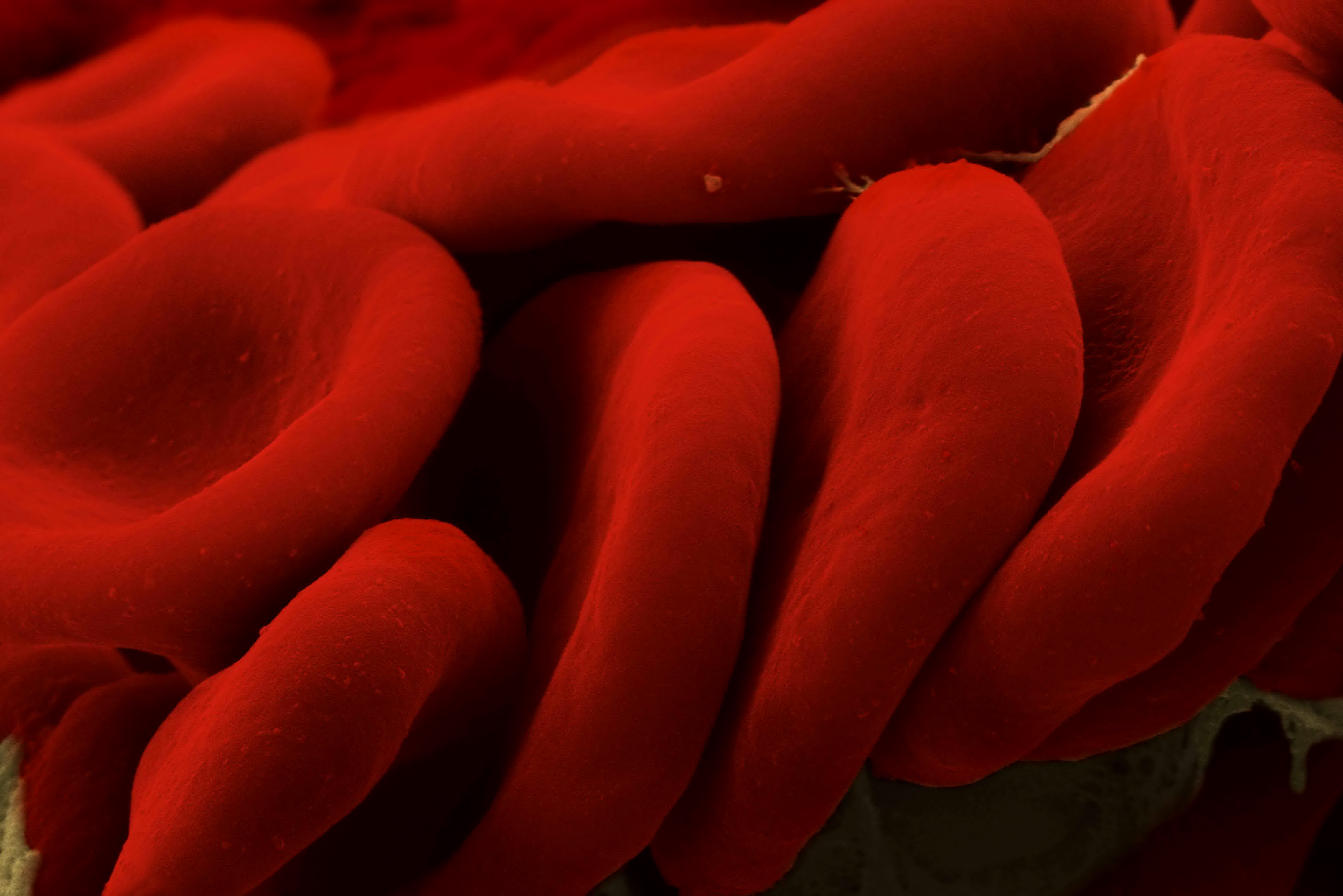

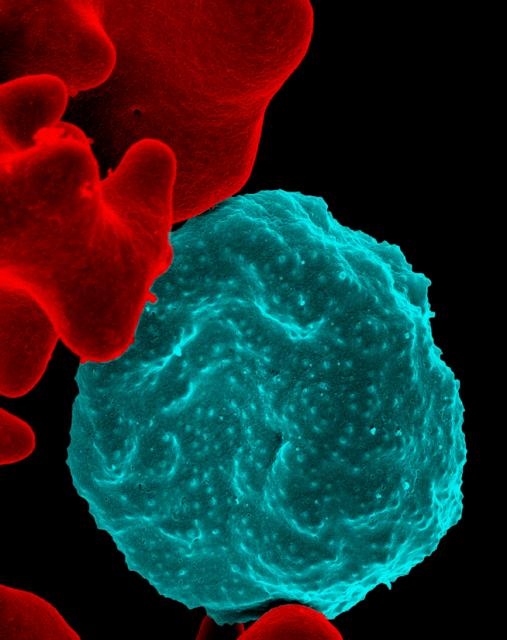

Red blood cells are some of the most important and oddest cells in our bodies. First of all, unlike all our other cells, red blood cells don’t have nuclei, DNA, or many other inner parts. The main things they have inside are molecules called hemoglobin (HEE-muh-glow-bin). The hemoglobin in red blood cells picks up oxygen in your lungs and carries it through your bloodstream to the rest of your body. And red blood cells move FAST. It takes just 20 seconds for one red blood cell to travel around your circulatory system.

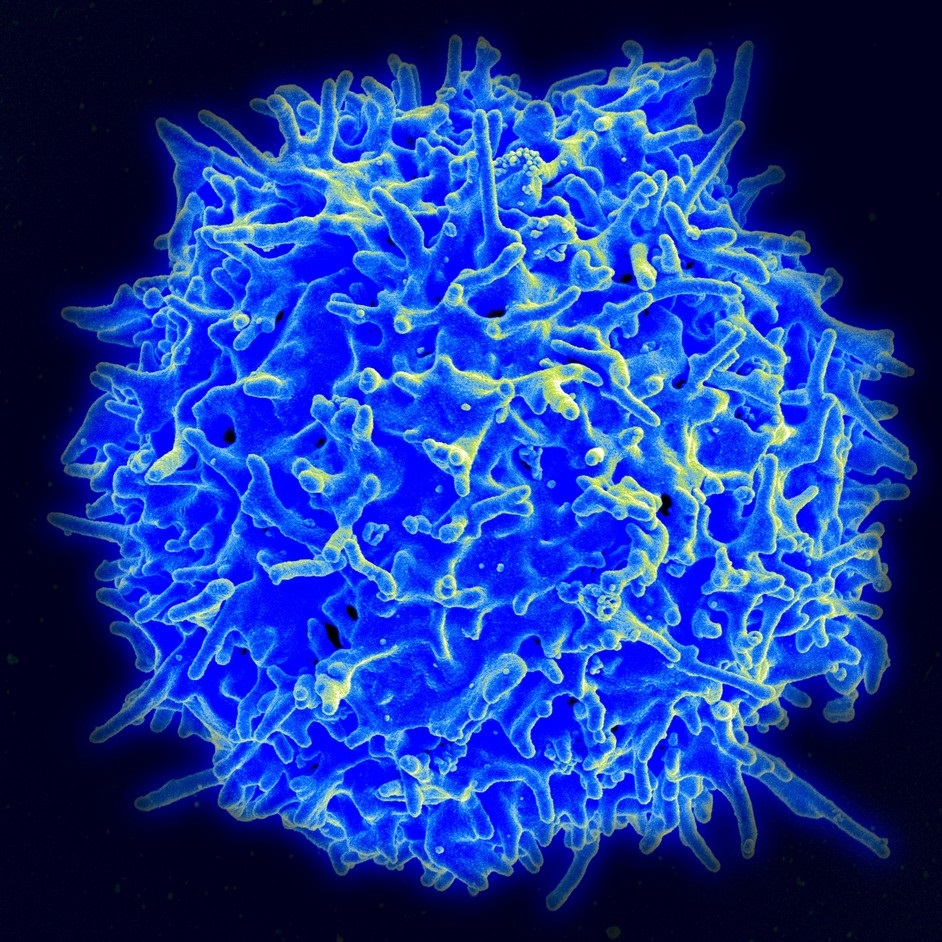

On TV, you may see scientists who work for the police department using blood stains to ID both criminals and crime victims. But how can they do that if red blood cells don’t have DNA? Your blood also contains white blood cells, which do have DNA. White blood cells are the guardians of the blood and they help fight off infections and disease.

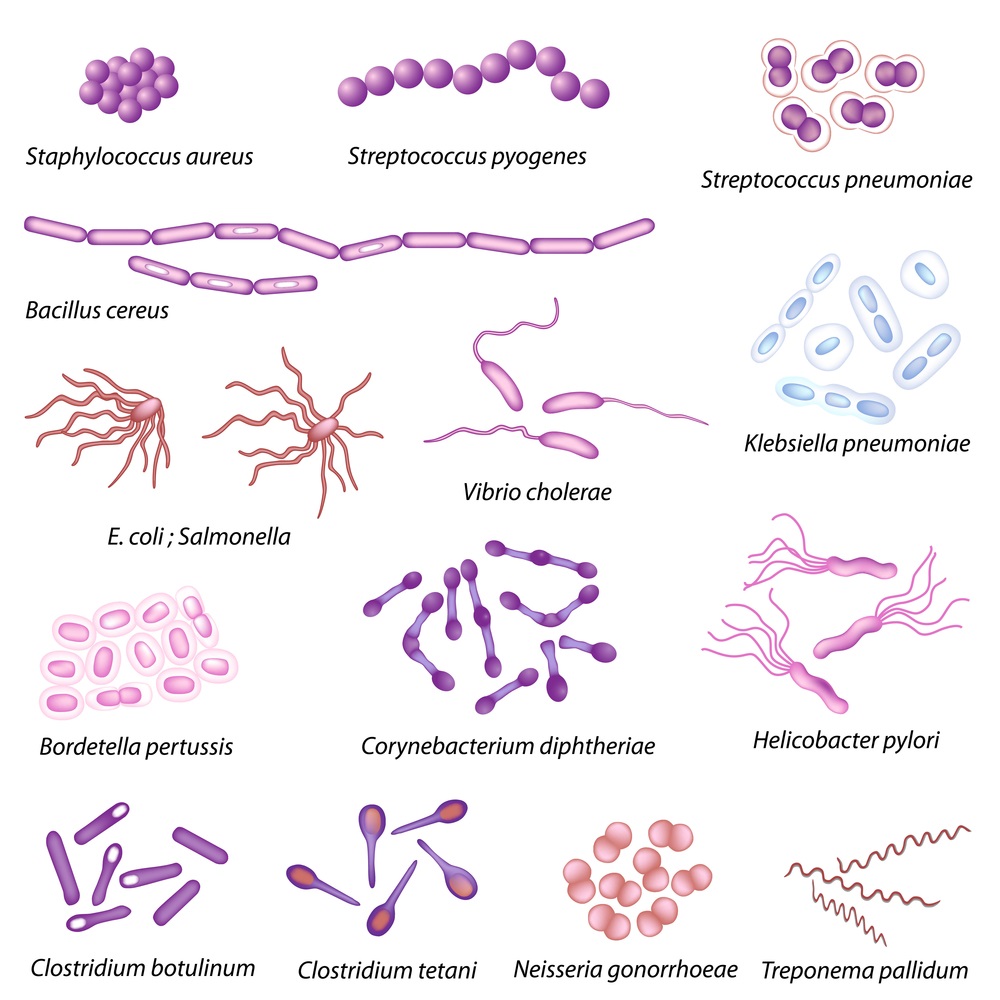

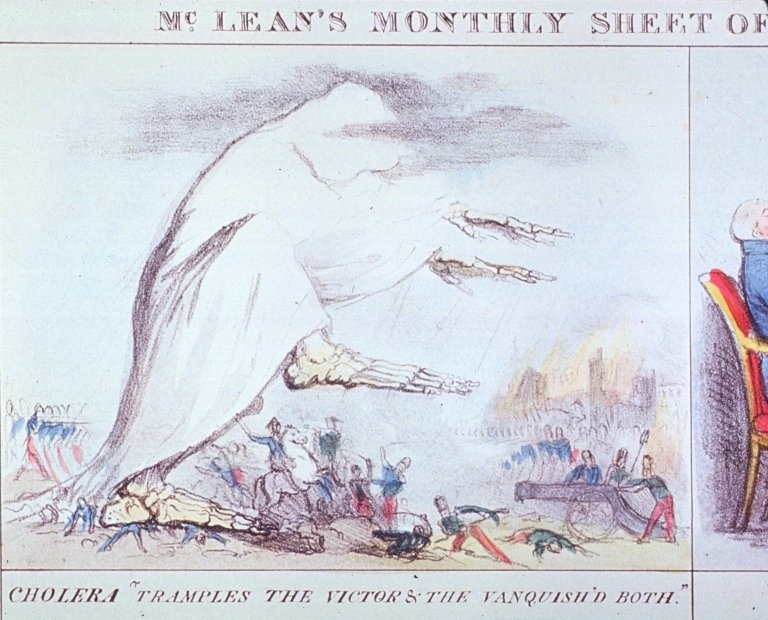

It took a long time for scientists to figure out what caused certain diseases—and some diseases are still being worked on. In Hooke and Leeuwenhoek’s day in the 1600s, a lot of people thought diseases were spread by “bad air.” What they meant by that was the funky-smelling air near garbage dumps or sewers. When Leeuwenhoek discovered microscopic life, scientists started wondering if microbes (a.k.a. germs) might be invading the body and causing diseases. That might seem obvious today, but it was such a radical notion back then that it took almost 200 years for the idea to be completely proved and accepted.

The credit for proving that specific germs cause specific diseases is usually given to the French scientist Louis Pasteur. Oddly, Pasteur didn’t make this discovery by studying humans, but by studying silkworms. In the 19th-century, France was the capital of the fashion world and silk was the premier cloth. But silkworms were suffering from a mysterious disease; they were dying in large numbers and the ones that survived couldn’t spin silk thread. The silk producers asked Pasteur to find a solution. Microscopic examination of the silkworms showed they were infested with two different disease-causing microbes. Observation showed that the germs were passed from silk moths to their eggs, and from the droppings of silkworms onto leaves that the silkworms ate.

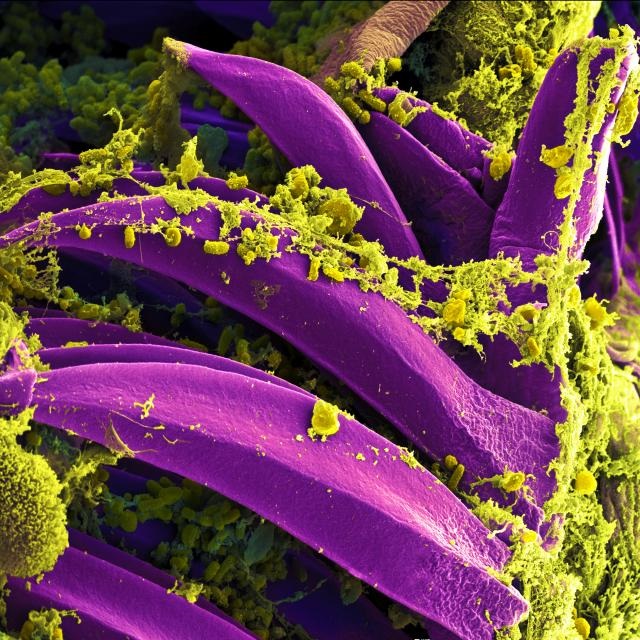

Pasteur had identified the specific cause of the disease. He had also identified how it was spread from one silkworm to another. Pasteur and other scientists soon realized that they needed to apply the same methods to discover the causes of human diseases. Within a few decades, the microbes responsible for many deadly diseases had been identified. Scientists began to look for vaccines and cures—a process that continues today.

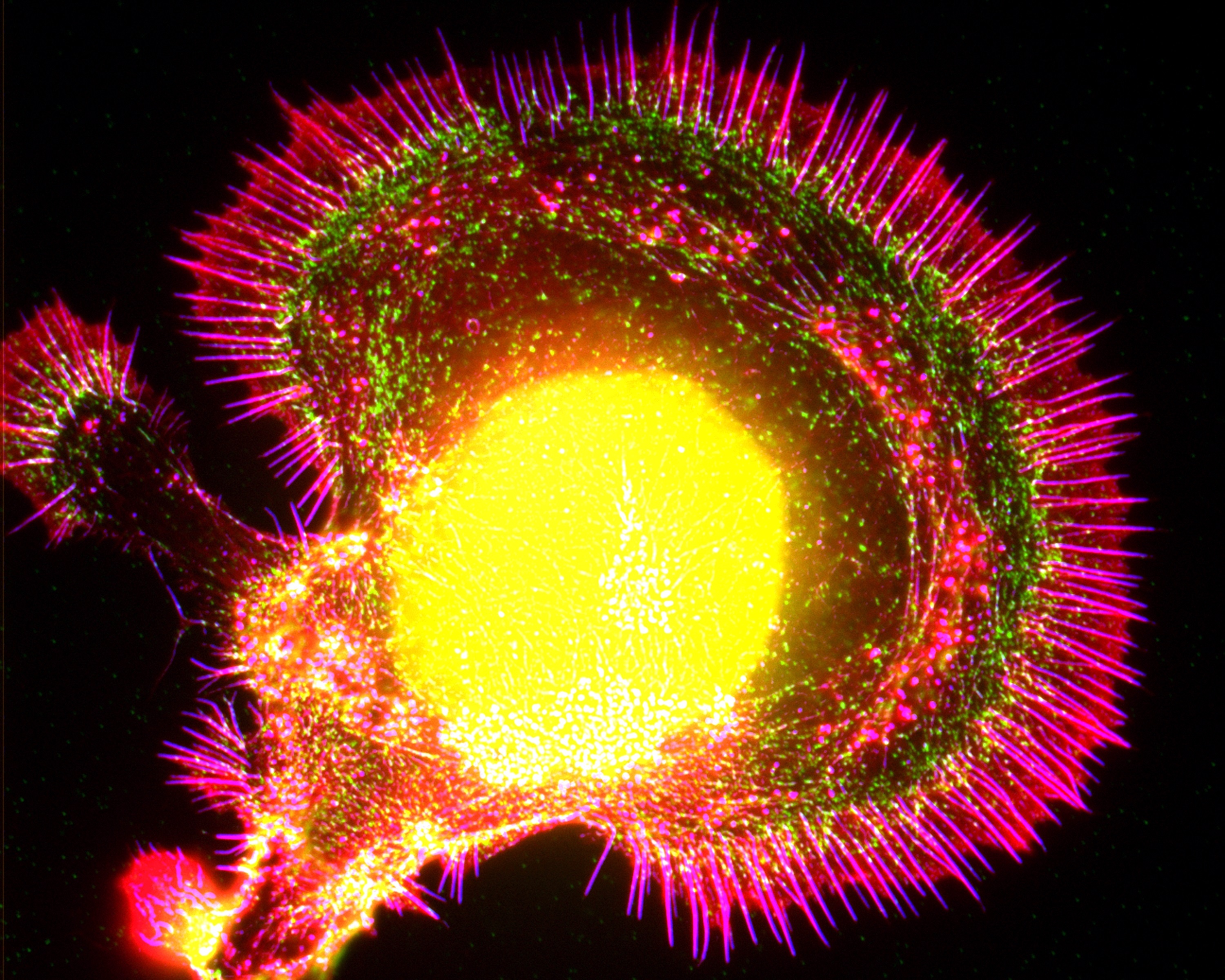

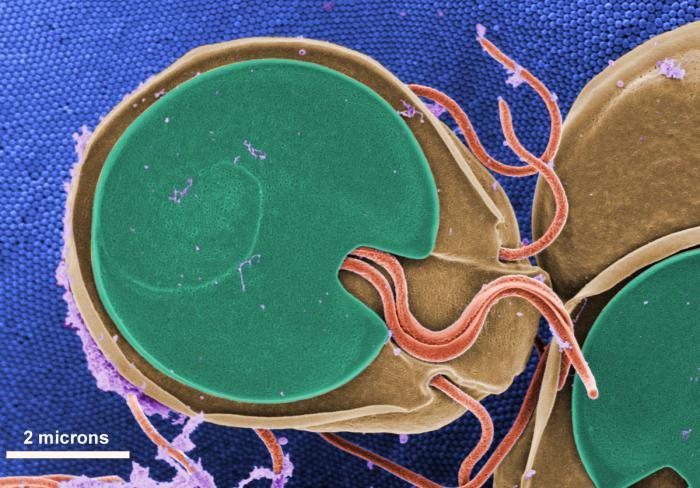

One of the most dangerous single-celled organisms in the world is one that causes malaria. Plasmodium falciparum is a protozoan that hitches a ride in the bodies of mosquitoes before getting into its real target: vertebrate animals. When a mosquito infected with the malaria parasite sips the blood of a human, the parasites slip into the human’s bloodstream, quickly ride the bloodstream to the human’s liver, and infect the liver cells. The parasite multiplies inside each cell until tens of thousands of new parasites burst the cell and move on to invade red blood cells, where they further reproduce. All this wreaks havoc on the human body, resulting in chills and fever—and in some cases death. While there are medicines to help cure malaria, scientists are still searching for a vaccine that will prevent Plasmodium from making people sick.

Of course, not all microbes cause disease. In fact, plenty of them mind their own business, and others are downright amazing. Extremophiles are single-celled microbes that can live in very weird places—places that scientists used to think were impossible for life to survive. They live underneath glaciers, inside rocks, and in the ocean next to boiling-hot deep sea vents.

Written by Margaret Mittelbach.

[wp-simple-survey-27]