What if you could change into a totally different form? What if you could grow wings and fly? What if you could gain new powers—like lifting 50 times your weight or jumping 5 times your height? That’s the stuff of science fiction and comic books. But it really happens when animals go through metamorphosis.

A body is not fixed like a statue. Bodies change as they grow—whether it’s a kitten growing into a cat or a child growing into an adult. But near-total change is rare—unless of course you’re an insect, jellyfish, frog, or other animal that goes through metamorphosis.

Zoologists use the term metamorphosis to describe what happens when the young, or juvenile, body of an animal goes through a radical change in form to become an adult.

An excellent example of metamorphosis is a caterpillar transforming into a butterfly. If you saw a caterpillar and a butterfly side by side, you might not realize they were the same creature. They look almost completely different. And they occupy different niches in their habitat, with the caterpillar stuck on land and the butterfly able to take to the air.

So how do they make this huge transformation? Butterflies and many other insects, such as ants and bees, have four major stages in their life cycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult.

The basics go like this: The adult butterfly lays tiny eggs, usually on a leaf, stem, or another part of a plant. Each egg is just one fertilized cell, but it has blueprints for the physical shape of the developing insect (in its DNA) and food in the form of a yolk to provide energy for growth. The mother butterfly spends a lot of time hunting for the exact right plant to lay eggs, because once they hatch, many caterpillars will only eat one type of greenery.

It only takes a short time for a small larva—called a caterpillar in the case of butterflies—to emerge from the egg. Born right on its food source, the caterpillar quickly gets to its favorite activity: eating. The life of the caterpillar is simple: It eats, poops, and grows. In fact, it grows so much that it repeatedly gets too big for its skin. A caterpillar typically needs to shed its skin five or six times as it grows. The process of shedding its skin is called molting, and each phase between molts is called an “instar.”

Caterpillars are not very speedy and they’re out there in the open—which makes them easy targets for predators. To help them survive, caterpillars have evolved two strategies: hiding in plain sight (camouflage) and chemical warfare (toxins). Caterpillar camo comes in many forms—some caterpillars look like bird poop, others like twigs, and still others have large eyespots to make them look scary to anyone thinking of attacking. Caterpillars that use toxins for defense sometimes have bright colors, effectively saying “Warning: Eat Me at Your Own Risk.” These toxic caterpillars can make birds and other predators sick if eaten.

After a few weeks, the caterpillar is ready to start its big transformation. It finds a safe place (such as the underside of a leaf) and spins a tiny pad of silk. Using Velcro-like hooks on its back end, it attaches itself to the silk pad and hangs upside-down. This time, when the caterpillar sheds its skin, there is a pupa underneath. A butterfly pupa is called a chrysalis. Soft at first, the outside of the chrysalis hardens in about an hour, creating a protective shell. As the pupa hangs there, the insect doesn’t eat or interact with the outside world. All the action is inside the pupa.

If you were to watch a sped-up film of what happens inside a chrysalis, it would look like part of the caterpillar’s body was turning to mush. What’s happening is that the caterpillar is digesting much of its own body—using some of the same secretions it used to digest leaves and other food. The digested body parts provide the energy for metamorphosis. Here’s how:

Among the parts of the caterpillar’s body that don’t turn to mush are tiny clusters of special cells that can grow into butterfly parts. These special cells are called imaginal discs. These stealthy cells have been hiding inside the caterpillar’s body all along—and they are just waiting for a trigger that tells them to grow. (The trigger is a drop in the production of juvenile hormone.)

The imaginal discs grow into wings, six segmented legs, compound eyes, antennae, and the proboscis that the butterfly uses to sip nectar. When the adult butterfly emerges from the chrysalis, it weighs about half its caterpillar self. That just goes to show how much of the caterpillar’s body had to be broken down into energy to fuel the transformation.

Other insects go through a four-stage life cycle, too. While they follow the same basic pattern—egg, larva, pupa, and adult—the details of their lives can be very different. For example, honeybee larvae don’t go off on their own and fend for themselves like butterfly larvae do. Adult honeybees care for wiggly, wormlike larvae in nurseries inside their hive. The larvae are fed literally hundreds of times a day and they grow FAST.

Honeybee larvae are ready to transform five days after hatching. When it’s time, the adult bees seal them into the hexagon-shaped honeycomb cells in which they were born and the larvae “pupate,” spinning little cocoons (with silk produced from their salivary glands). To spin a cocoon around itself, a larva turns dozens of somersaults inside the honeycomb cell. There, the larva goes through metamorphosis—a process that takes 13 days—changing from a little white grub into an adult honeybee with six legs, a stinger, wings, and black and yellow stripes.

About 88 percent of all insect species have a four-stage life cycle and go through complete metamorphosis. The remaining 12 percent—including dragonflies and grasshoppers—have a three-stage life cycle and go through what is called simple metamorphosis. The three stages are: egg, nymph, and adult. The key difference between complete and simple metamorphosis is there is no dormant, or “resting,” stage. Nymphs are born looking somewhat like their adult forms, and with each molt they take on more adult characteristics.

About 88 percent of all insect species have a four-stage life cycle and go through complete metamorphosis. The remaining 12 percent—including dragonflies and grasshoppers—have a three-stage life cycle and go through what is called simple metamorphosis. The three stages are: egg, nymph, and adult. The key difference between complete and simple metamorphosis is there is no dormant, or “resting,” stage. Nymphs are born looking somewhat like their adult forms, and with each molt they take on more adult characteristics.

Dragonflies go through a dramatic three-stage metamorphosis. When the nymphs first hatch, they look like small beetles. But they’re aquatic and have gills so they can breathe under water in ponds and rivers. As the dragonfly nymphs grow, they shed their skin (molt) several times and with each molt, they grow longer and start developing “wing buds.” A nymph may molt 8 to 15 times before it’s ready to emerge from the water. For the final molt, the nymph crawls out of the water and clings to the stalk of a plant. It sheds its skin and then starts pumping a blood-like substance into its four wing buds—which expand and turn the now-adult dragonfly into one of the most amazing fliers on the planet.

The final molt is often triggered by a change in season or temperature. In some cases, nymphs of one species in a pond or stream may all transform on the same day. Mayflies are famous for their mass emergences each spring. Sometimes there are so many that they create blizzard-like conditions and can even be tracked by radar.

Frogs have a three-stage life cycle, too: egg, larva, and adult. The mother frog deposits her eggs in a pond or other wet environment. When the eggs hatch, tiny larvae (tadpoles) emerge. Tadpoles, of course, are aquatic—they have gills and long tails, and they swim around like fish. But toward the end of the tadpole phase, changes happen: Legs and lungs begin to form, the tadpole’s tail shrinks, and its mouth widens. When metamorphosis is complete, the adult frog is so changed that it hops out of the water and lives on land from then on. Once legless, its legs are now so powerful that they make up one-quarter of the frog’s body mass. Some frogs can leap 10 to 20 times their body length.

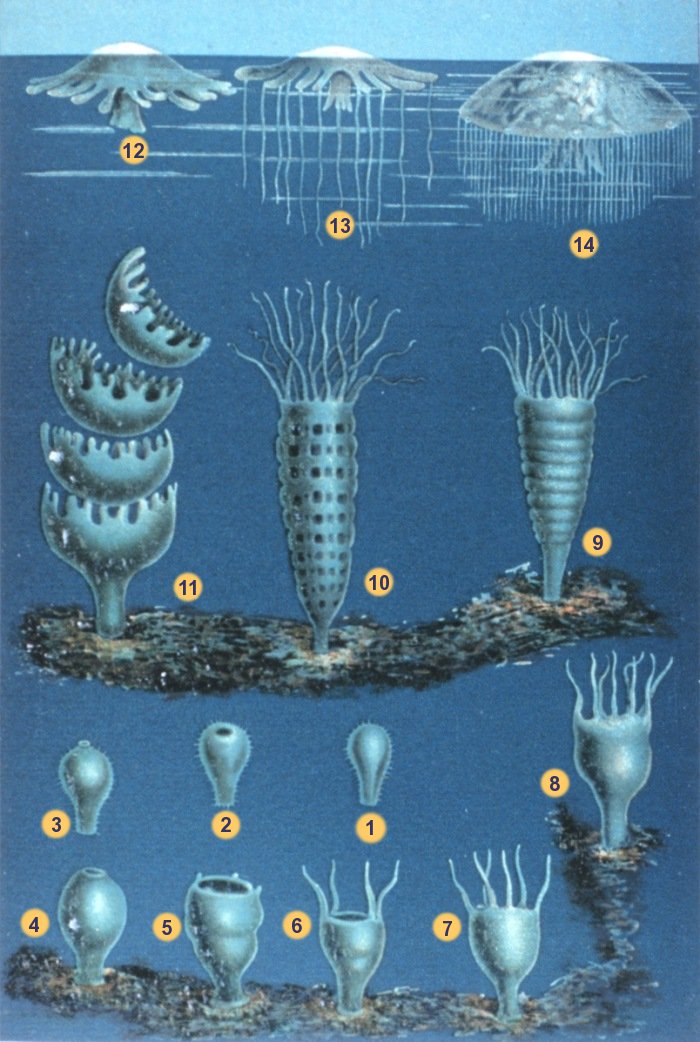

Jellyfish are freaky to begin with. But their metamorphosis is even freakier. You’re probably familiar with adult jellyfish, with their umbrella-shaped bodies and tentacles. The adult form is actually known as the medusa because of its resemblance to Medusa—the angry snake-headed goddess in Greek mythology. But that’s not the only form. Jellyfish start their life as tiny free-swimming planulae that quickly attach to a surface and grow into a polyp. The polyps are cup-shaped with mouths and tentacles. The polyp just sits there—trapping passing food—until a change in water temperature triggers it to morph and start “budding off.” Little disks of new jellyfish bud and break off from the polyp. The disks grow into adult jellyfish that can swim around on their own—and sometimes lash out with stinging tentacles.

Written by Margaret Mittelbach

[wp-simple-survey-32]