Mock Trial

- April 7, 2015

- By Marjorie Frank

Earlier this year, I was called for jury duty and picked to serve. Friends I told most often expressed sympathy for my misfortune. But I look at it differently. First, jury duty is a responsibility of citizenship; make no mistake about that. Our system — our concept of a fair trial — rests on a process of advocacy to decide guilt or innocence, which is done by a jury of ordinary individuals, like you and me.

Beyond fulfilling my civic responsibility, I find jury duty to be a fascinating experience. I get to see the back-and-forth of a real trial (in contrast to a TV trial). I also get to know people, other jurors, who I probably would not otherwise meet. This is all to the good and relevant to us as educators.

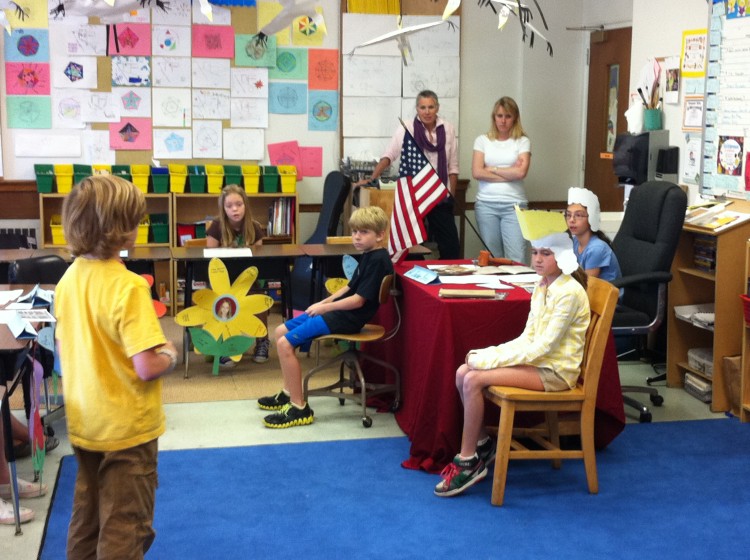

Preparing students to fulfill their future civic responsibilities comes under our umbrella. Having students participate in a mock trial is one strategy for doing so. It has the added benefits of causing students to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate; to develop listening skills; and to gain confidence in public speaking.

To plan and carry out a mock trail, all you need is a set of facts, a statement of the relevant law, and students to role-play the individuals in the trial. For a civil (noncriminal) case, that includes the plaintiff or person making the complaint, the lawyer for the plaintiff, the defendant, the lawyer for the defendant, witnesses if any, the judge, and the jury.

For first-timers, the facts should be fairly straightforward. You can use the situation below or find other sample cases by doing a key-word search such as “[Name of State] Bar Association Mock Trial Middle School.”

Martha raked the leaves in her neighbor’s yard every Sunday during the fall. One Sunday Martha was sick, so she asked her friend Ted to rake for her. Martha agreed to pay Ted $20. Ted raked the leaves and left, but soon after he left, a wind kicked up and spread the leaves over the lawn. The neighbor, having returned from an all-day outing, called Martha to complain about the leaves and refused to pay her. When Martha went to inspect the lawn, she saw that the neighbor was right; leaves were everywhere. Martha photographed the lawn and refused to pay Ted the $20.

The law of Contracts applies to this situation. A contract is an agreement between two or more parties, which creates an obligation to do or avoid doing a particular thing. In this case, Ted’s obligation is to rake the neighbor’s lawn. Martha’s obligation is to pay him $20 for doing so.

In making a mock trial happen, you can follow a plan of action similar to this:

Step 1: Discuss the facts of the case and the relevant law with students.

Step 2: Identify the people involved in the trial: plaintiff, defendant, witnesses, judge, jury, and lawyers.

Step 3: Summarize each person’s role.

In the sample case, Ted is the plaintiff; Martha is the defendant. The judge’s role is to make sure everyone follows the rules of the trial. The jury’s role is to decide what happens and who wins. The role of the plaintiff’s lawyer is to question witnesses in order to present the facts in the most favorable light for the plaintiff. The same is true for the defendant’s lawyer.

Step 3: Outline the structure or flow of a trial:

- Opening arguments, when the lawyers tell the judge and jury what they will show

- Testimony, when witnesses answer lawyers’ questions about the case

- Closing arguments, when the lawyers tell the judge and jury what they have shown

- Deliberation, when the jurors discuss and decide the case

Step 4: If your students are older, you may want to acquaint them with the concept of evidence. Legal evidence is proof. In the example, Martha’s photograph of the neighbor’s lawn may be evidence. The neighbor’s testimony may also be evidence.

Rules govern the evidence that can be used in a trial. This is probably the most fundamental rule of all:

- Only evidence relevant to the case may be used.

For example, a photograph of the neighbor’s lawn taken after the leaves were raked may be relevant. A photograph of someone else’s lawn is probably not relevant. Lawyers can argue at great length about whether a particular piece of evidence is relevant or not.

- Even relevant evidence can be prohibited if it causes unfair prejudice.

Say Ted wants to tell the jurors that he thinks Martha is a mean person. Any relevance this could have is substantially outweighed by the danger that it would cause jurors to be unfairly prejudiced against Martha. The evidence would not be allowed. This rule gives the judge (i.e. you or a student) control over the trial and a way to redirect students to the relevant issues in the trial.

Say Ted says that in the past Martha has lied about pictures she’s taken. This evidence may be relevant to whether the jurors believe what Martha says about the picture. The judge would have to decide whether to allow the evidence or not.

Step 5: Now you’re ready to go. Assign or have students select their roles. To involve the whole class, have two or three students work together on some roles and increase the number of jurors.

As part of students’ “training,” you may want to have them read and discuss a pre-scripted trial. You’ll find sample scripts at these sites:

- http://19thcircuitcourt.state.il.us/resources/documents/publications/mt_bbwolf.pdf

- http://www.justiceeducation.ca/resources/Advanced-Mock-Trials

Some scripts are based on real-world cases; others center on fairytales like Cinderella, which students are sure to enjoy.

Creating a mock trial is definitely something your students will not forget….and who knows where it may lead…. you may have some future lawyers in your midst!

___________________________

The legal information in this post was vetted by Denver attorney and former middle school teacher Adam Frank. (Mistakes are all mine, however.) For more information and videos of mock trials, check out these sites:

- http://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/resources/lesson-plans/middle-school/due-process/mock-trial-plan.html

- http://www.scbar.org/Teachers-Students/All-Programs/Middle-School-Mock-Trial/Resources

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L6c-5DiWCKs (a middle school mock trial in action)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qtQDOQM4dM8 (walkthrough to show the flow of a trial)