The Life of Pie (Chicken Pot, that is)

- June 3, 2013

- By Michael Kline

In 1990 the government of the United States signed into law the Nutritional Labeling and Education Act (the NLEA), basically stating that all food sold within the country be labeled with nutritional information, and requiring that those nutrient claims meet FDA (Food and Drug Administration) guidelines. Pull any can of soup or box of cereal from the shelf at the grocery store, and somewhere upon the package you’ll find a space labeled Nutrition Facts. Though they are never meant to be groundbreaking works of nonfiction (take a can of red kidney beans to bed and I guarantee that reading the label will put you to sleep in minutes), they are quite full of good, hard information. And if you’re looking for those “breakout” kinds of characters while you read, you’ll find that sodium (salt) and high fructose corn syrup (sugar) star in recurring major roles.

In 1990 the government of the United States signed into law the Nutritional Labeling and Education Act (the NLEA), basically stating that all food sold within the country be labeled with nutritional information, and requiring that those nutrient claims meet FDA (Food and Drug Administration) guidelines. Pull any can of soup or box of cereal from the shelf at the grocery store, and somewhere upon the package you’ll find a space labeled Nutrition Facts. Though they are never meant to be groundbreaking works of nonfiction (take a can of red kidney beans to bed and I guarantee that reading the label will put you to sleep in minutes), they are quite full of good, hard information. And if you’re looking for those “breakout” kinds of characters while you read, you’ll find that sodium (salt) and high fructose corn syrup (sugar) star in recurring major roles.

Labels are required to have certain information: Serving size information (as a standard), calories, calories from fat, fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrates, dietary fiber, sugars, protein, vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron. Values are shown by weight and percentage (of daily value, based on a 2,000-calorie diet for healthy adults), and nutrients whose values are zero are left off the list.

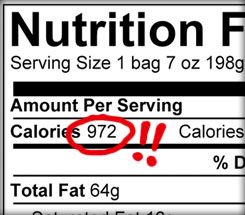

Packaged foods are also required to show ingredients, which can be very telling as they are required to be listed in order from highest to lowest quantity, according to their weight. Here is where you will find our friends sugar and salt making their marquee-worthy appearances. (If you want to have some frightening fun, search Google Images for Chicken Pot Pie Nutrition Label, paying close attention to the serving size. I’ll even wait while you do it…)

Hmmmm hmm hmmm… are you back? Feel your heart tightening up? My breath got a bit shallower just by reading those. And I suddenly feel a teaching moment coming on, as opposed to say, a heart attack.

Have your students bring a food container from home, preferably one that is empty and rinsed, and makes a frequent appearance in their household (ergo, something their parents either willingly or under child-equated duress purchase often at the local grocer). Have them compare totals and percentages, paying particular attention to proteins (that help keep muscles, skin, and hair healthy), carbohydrates (sources of energy; sugars giving quick energy levels and starches giving longer lasting energy), oils and fats (used to help the body retain vitamins and build tissue), and vitamins (necessary to help the body use those carbs, proteins, and fats).

A calculator can also come in handy when processing this information, so you might want to have one handy. If you have a set of measuring devices handy (cups, spoons), ask the kids to guess at what a serving size is, then show them the real life version. You can even carry this exercise over into the school cafeteria, asking your students to check the labels on anything they can find. Have your charges take their information on the road when they visit grocers, restaurants (if it’s not posted, they may need to ask to see it), and fast food establishments, and give extra credit to those who report and share their findings. (For instance, the Burger King Double Whopper Sandwich meal sports 1,360 calories and 1,790mg of sodium, roughly the maximum daily requirement for an adult–in one meal.)

Engage the kids in a discussion as to the winners and losers of the nutrition label exercise, and why some foods fail and others exceed. Watch for the more egregious examples of poor nutrition (sodas and breakfast cereals) as well as the foods that offer beneficial, balanced nutrients (foods with beans, whole grains, and vegetables).

Perhaps the most important aspect of nutritional information is one that is not included on the label, but merits a good talk (with you as the teacher as well as the parent), and that is moderation. Anyone can benefit from most any food available for sale today, but the people that will do the best are those that know when too much is actually “too much.” Teach your students that it’s not imperative that they finish the entire can of Pepsi. Show them how to take an amount upon their plate that they will actually finish versus what they feel required to eat. Ask them if they eat from hunger or from habit (“It’s noon! Time to eat!”).

And just step away from the chicken pot pie…

Teach. Learn. Enjoy!