Engines give people the power to do what was once only possible in myths and dreams. Thanks to engines, you can fly halfway across the world in half a day. Astronauts can rocket up to the International Space Station in six hours. Helicopters can rescue injured people and speed through the sky to the hospital.

We live in a world filled with engines. They’re mostly out of sight, under the hoods of cars, in trucks and buses. But you can hear them, purring at red lights, rumbling down highways, revving as motorcycles race past, and roaring in planes overhead.

One hundred years ago, that familiar sound would have been uncommon. And just a few hundred years before that, the Earth was engineless. So what inspired the early inventors of engines? Was it the wonder of flight and the dream of speed? Not exactly.

The engine was invented to solve a problem. Weirdly, the problem wasn’t how to power a train or to lift a plane off the ground. The problem was how to get water out of coal mines.

Here’s what was going on: Around the year 1600, people in the cities of Great Britain were running out of firewood to warm their homes and cook their food. The growing population had chopped down so much of the forest around cities that firewood was getting hard to find. People needed another source of fuel.

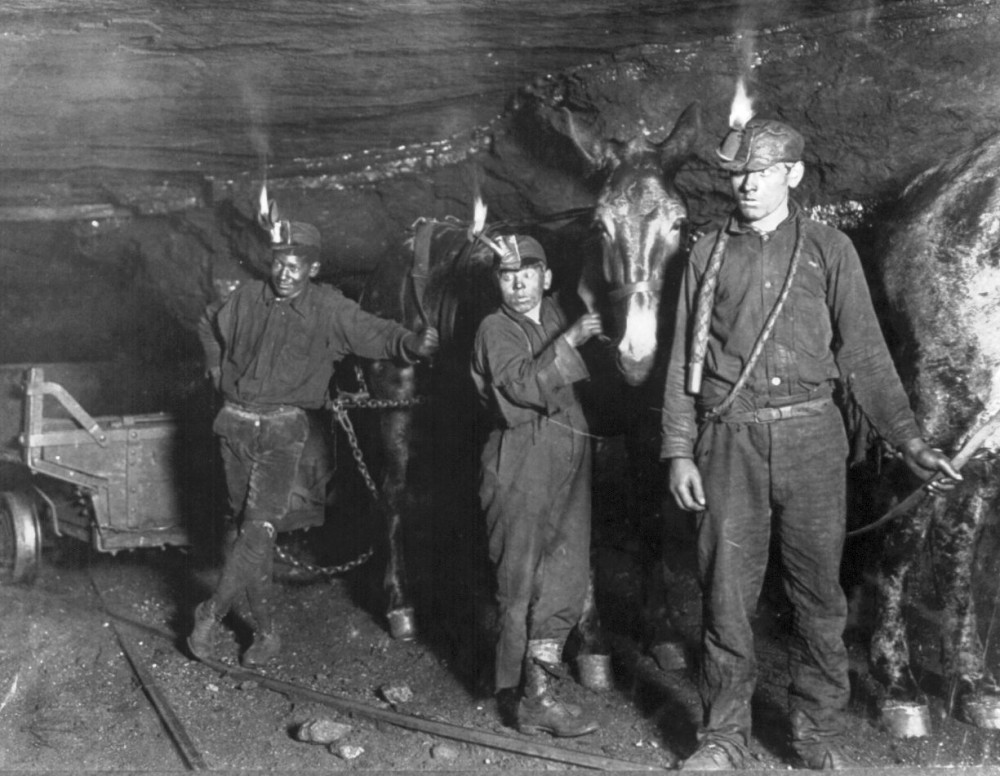

Coal—a black fossilized rock buried deep in the ground—became that new fuel. Coal was dirty and dangerous to mine, and it created choking black smoke when it was burned. But there was plenty of it. Huge coal mines were opened, and miners dug tunnels to get at the coal, bringing up ton after ton.

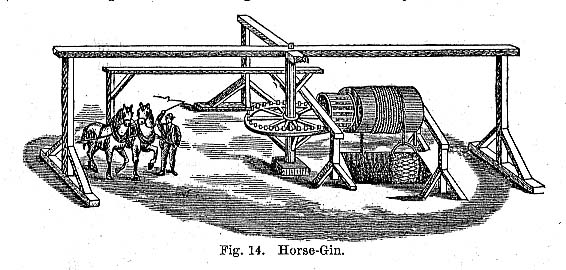

Among the many challenges of coal mining was the problem of flooding: Water naturally seeped into the mines, and it could flood the tunnels and drown the miners. In the 1600s, big pumps and lifts were built to draw out the water. They were powered by horses walking in a circle and pulling a crank. These machines were called horse engines (or “horse gins” for short).

Horse engines were a clever way to get water out of coal mines. But was there a way to do it faster? The faster the water could be pumped, the more coal could be dug. The “need for speed” inspired inventors to keep tinkering.

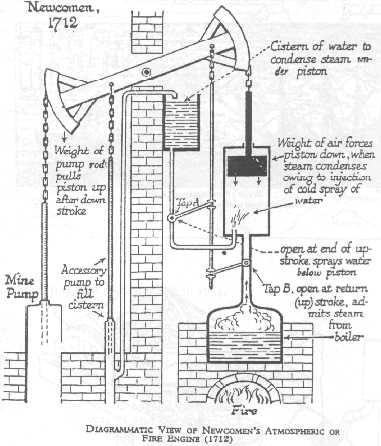

In 1712, an English inventor named Thomas Newcomen came up with a machine—a steam engine—that could remove water from mines. Instead of horses, the power source for the engine was (conveniently) coal. In the Newcomen steam engine, coal was burned to heat water in a boiler. The boiling water created steam that drove a piston upward. When cold water was sprayed on the hot steam, the piston moved down again. The up-and-down motion of the piston moved a lever that looked like a teeter totter—and the lever operated a pump which drew water out of the mine. Newcomen’s steam engine could do the work of 20 horses, and it was eventually used in coal mines all over England.

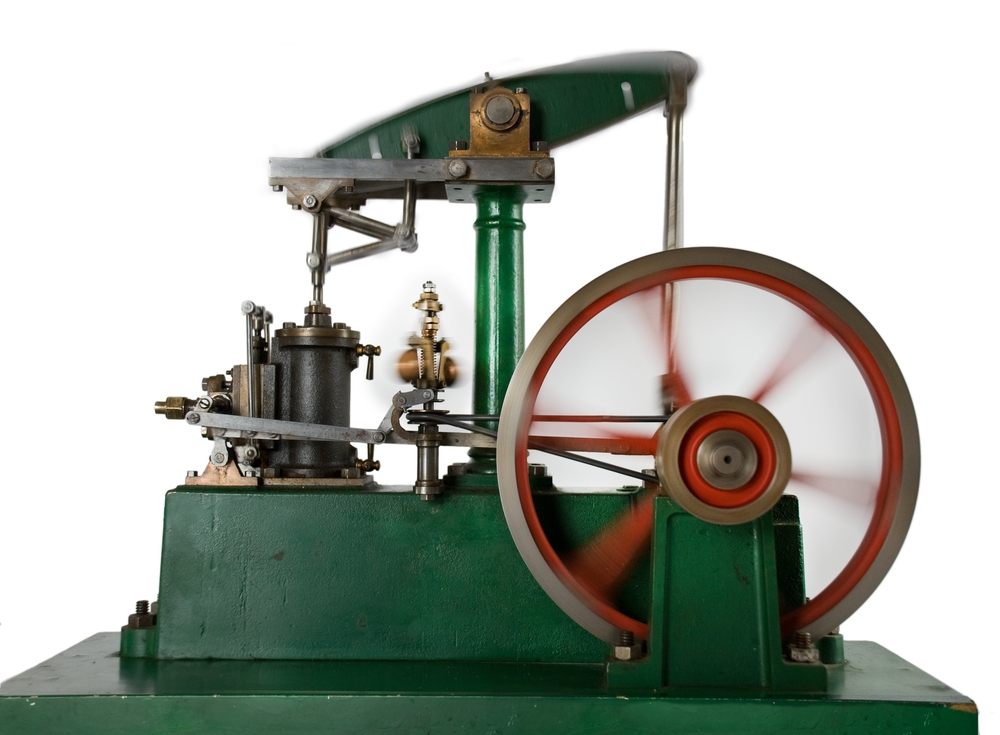

The Newcomen engines used HUGE amounts of coal for fuel, and that seemed OK at first because the mines had plenty. But did the Newcomen engines really need to burn quite so much? A lot of energy from the coal was wasted. In 1765, a Scottish inventor named James Watt figured out a way of redesigning the steam engine so that it would use less coal and do more work. And then he went one step further: He figured out a new way to make the up-and-down motion of the piston turn a wheel. That seemingly simple innovation radically changed the world.

Watt’s steam engine powered more than pumps. It powered the entire Industrial Revolution. Factories that ran machines using steam engines popped up across England and America in the 1800s. The steam-powered wheel meant a revolution in transportation, too.

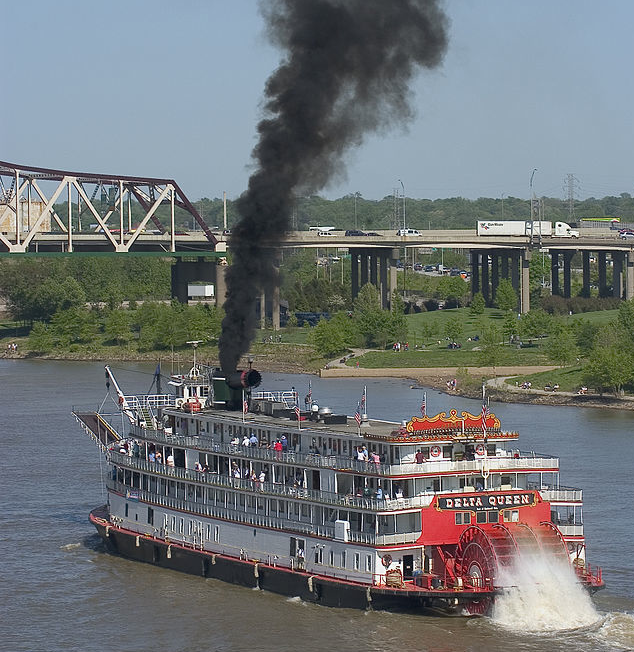

In 1807, the American inventor Robert Fulton drew plans for a steamboat and hired Watt’s company to build the engine. It was designed so the engine would drive two paddlewheels to propel the boat through the water. Fulton thought it would go much faster than boats with sails. And his plan was to take passengers on the Hudson River from Albany (New York’s state capital) to New York City. Many people thought Fulton was going to fail—and they called the whole idea Fulton’s Folly.

On the day of the first test trip, everything didn’t go perfectly. When Fulton first announced he was ready to steam upriver, the engine wouldn’t start. Embarrassing! But Fulton tinkered with the engine and got it working. His steamboat chugged through the water, the paddlewheels on both sides churning. Huzzah! Fulton’s steamboat was open for business, and other steamboats soon began making trips up and down American rivers and canals, carrying passengers, grain, coal, and other products.

Back in England, steam power was revolutionizing land transportation. And the original inspiration was once again in the coal mines. George Stephenson practically grew up in the English mine where his father worked feeding coal into the steam-powered water pump. And when George began working in the mines himself, he became an expert at fixing and building steam engines, even building small steam-powered locomotives that could haul coal cars along tracks in the mines. Soon, George was being asked to build larger trains to carry not just coal, but passengers too.

In 1829, a contest was held to see who could design the best locomotive for the world’s first major city-to-city railway—the 35-mile Manchester to Liverpool line. George Stephenson and his son, Robert, built and entered their locomotive the Rocket, and it beat all the competition. George won the contract to build all the locomotives for the new line—and its success set off a railway construction boom. Steam trains began crisscrossing England, America, and the world, connecting people, places, manufacturers, and markets like never before.

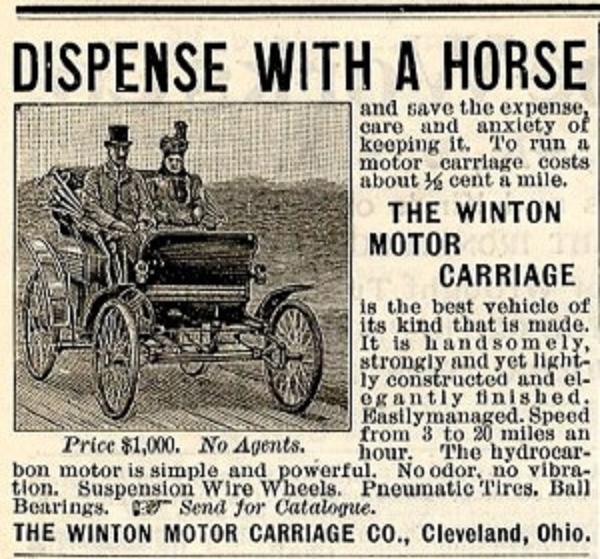

While trains dominated the rails in the 1800s, the roads were still filled with horse-drawn carriages. Could engines replace horses and power personal vehicles?

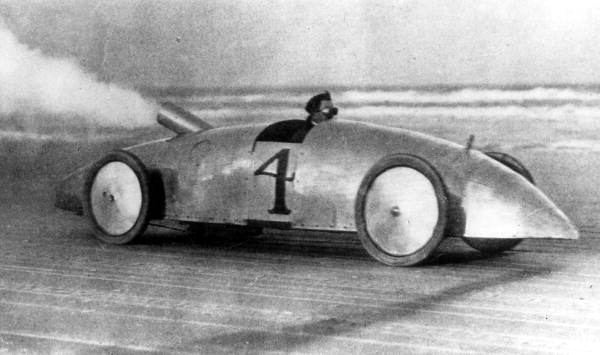

In the year 1900, there weren’t a whole lot of cars, but there were many different kinds of engines. There were steam-powered, gasoline-powered, and electric car motors. In the early days, car engines didn’t work so well. They could boil over, explode, or just stop working.

To catch on, cars needed reliable engines. The solution was a gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine. The first ones were made in France and Germany, but once they caught on in America, the United States became the car capital of the world. In 1895, there were about 300 cars on the road in the United States. Just 15 years later, there were close to half a million.

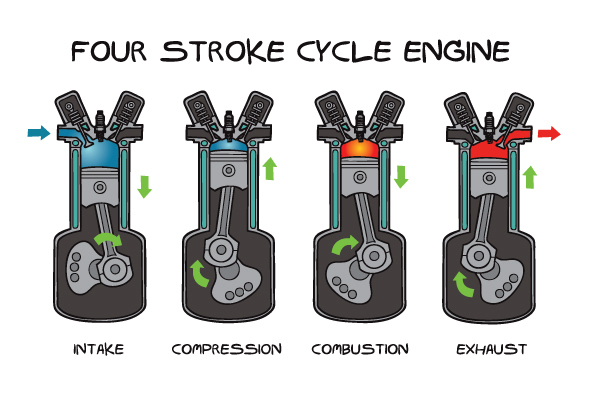

How does an internal combustion engine work? Like steam engines, internal combustion engines have pistons that move back and forth inside hollow cylinders. Unlike steam engines, the “fire” or combustion that causes the pistons to move is inside the cylinders. The fact that the fire is inside is why these engines are called “internal” combustion engines.

A typical car engine has what’s called a four-stroke cycle: intake, compression, combustion and exhaust. On the first stroke, the piston moves down and sucks fuel and air (intake) into the cylinder. Second, the piston moves up, compressing the fuel and air mixture. Third, a spark at the top of the cylinder lights the fuel, causing a tiny explosion (combustion) which pushes the piston down again. Fourth, the piston moves up again blowing out exhaust left over from the burning of the fuel. The back-and-forth movement of the pistons turns the crankshaft which turns the wheels of the car.

Engineers are always coming up with new ideas to make cars that use less fuel, create less air pollution, and reduce our carbon footprint. So gasoline-fueled four-stroke engines aren’t the only engines on the road. Two-stroke engines are used on motorbikes. Diesel engines—which are used on trucks, modern trains, and a growing number of cars—take a slightly different type of fuel and don’t need a spark to drive the engine process. Hybrid cars combine a traditional gas engine with a battery-powered electric motor. Electric cars don’t have standard engines at all.

The piston-driven internal combustion engine was, in fact, used to get the first planes into the air. But the engine had to be modified, and the cylinders were arranged in a “radial” formation (like the petals on a daisy) to power the propellers. When commercial aircraft with propellers were introduced in the 1930s, their average speed was about 165 mph. (These types of engines are still used in many small private planes today.)

To speed things up in the sky, engineers developed the fanjet, which made its first commercial flight in the 1950s and is still the most popular type of airplane engine today. A fanjet burns fuel, but rather than driving pistons or propellers, the power is provided by thrust from the exhaust “jetting” out the back of the engine through a nozzle (and pushing the craft through the air) and big turbofans that also produce thrust.

Rocket engines are like jet engines, with the exhaust “jetting” out the back. The main different is that rocket engines use special fuel and are designed to produce tremendously high pressure and thrust. That’s why you see massive amounts of flame and gas coming out of a rocket when it blasts off.

Written by Margaret Mittelbach

[wp-simple-survey-37]