High in the Himalayan mountain range of Asia, climbers cling to a treacherous slope. Every step is a struggle. Finally they reach the summit. They have summited Mount Everest, the tallest mountain on Earth. At 29,035 feet tall, it’s five-and-a-half miles high. What a view!

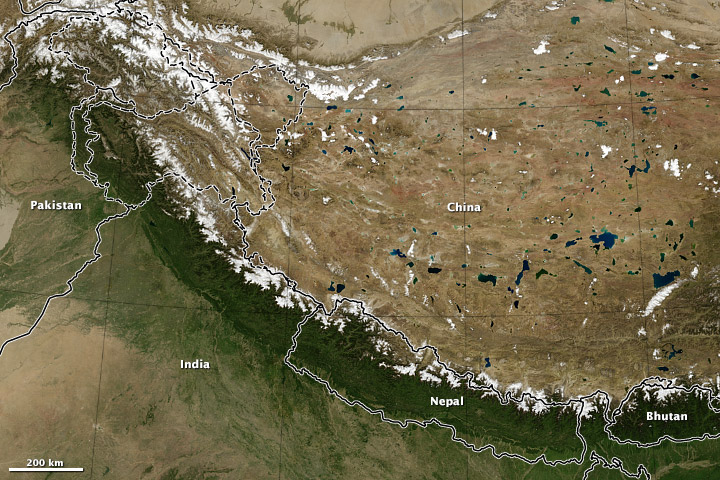

The Himalayas are by far the tallest mountains in the world. This mighty range stretches 1,500 miles from east to west, across Bhutan, Nepal, India, Tibet, China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Mount Everest may be the loftiest peak in the range, but dozens of other ice-clad Himalayan peaks also scrape the sky at over 25,000 feet. It’s the only place on the planet with any mountains so tall. No wonder the Himalayas are called the “rooftop of the world.”

Collision!

How on Earth did such tall mountains rise? A seriously big collision is how! The mega-collision is between two of the gigantic slabs called plates that make up Earth’s outer layer. The Earth’s plates slowly move, carrying continents along with them. As they move, the plates either grind past each other, pull apart, or collide head-on like a train wreck.

Just such a head-on collision has pushed the Himalayas sky-high. The mountain range got its start about 40 million years ago, as India began slowly crunching into Asia. That collision is still going on, so the Himalayas keep getting taller. To find out how fast, geologists put a Global Positioning System (GPS) instrument near the summit of Mount Everest. They determined that each year, the mountain gains another 0.1576 inches.

That may not sound like much, but after 40 million years it adds up. In fact, the rocks on the summit of Mount Everest formed at the bottom of the ocean! These top-of-the-world rocks even contain fossils of ancient sea creatures.

Into the Sky

The collision has pushed up three parallel sub-ranges that make up the Himalayas. The ranges are like a giant set of steps. The lowest, southernmost range rises up to 4,500 feet from the flat, steamy plains. This is the Outer Himalayas, or Shivalik Hills. Compared to the other two Himalayan ranges, the Shivalik Hills are rolling and gentle.

Next up are the Lesser Himalayas, north of the Shivalik Hills. This range is about 50 miles wide, with deep valleys and steep, dramatic gorges. The mountains here rise to about 9,000 feet.

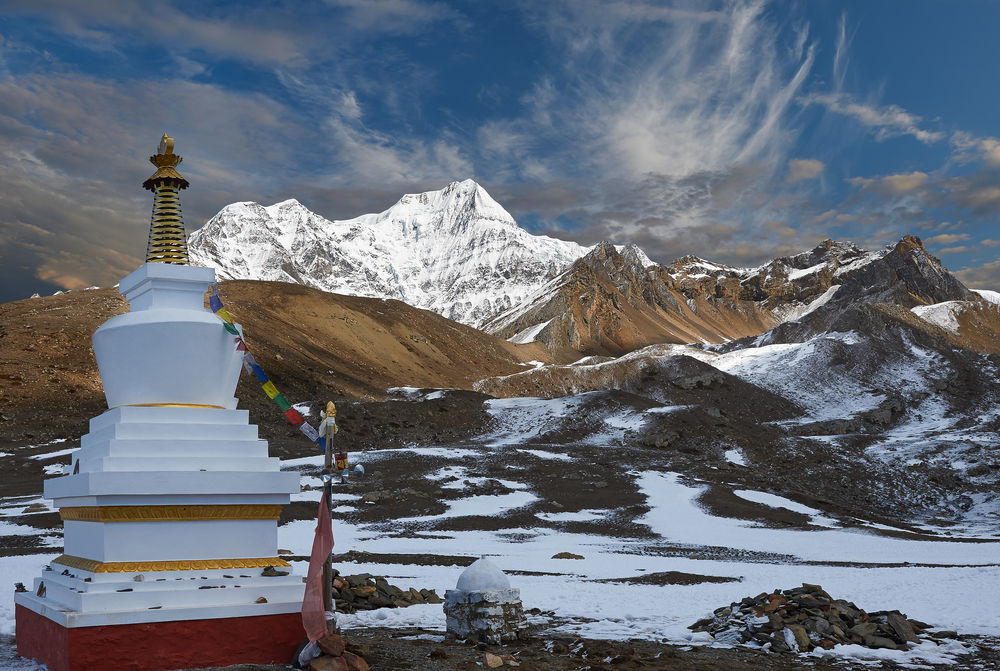

The northernmost range is the one you probably think of when you think of the Himalayas. This range is called the Greater Himalayas. It is a world of extremes. As the mountains rise above 12,000 feet, the climate becomes too cold for trees. Instead, stark boulder fields, alpine meadows and groves of shrubby rhododendrons lead skyward to vast fields of ice and snow. The mountains are frosted by at least 15,000 glaciers. The Greater Himalayas contain more ice than anywhere outside Earth’s polar regions. The very name “Himalaya” means “abode of snow” in the Sanskrit language.

Big Mountains, Big Effects

The Himalayas are so big that their influence ripples across thousands of miles. Most importantly, they are a source of water. Nearly 1,000 miles south of the Himalayas, for example, Pakistani children splash in the Indus River. The water may be warm, but this big river started as Himalayan snow. Three of Asia’s most important river systems – the Indus, the Yangtze, and the Ganges-Brahmaputra – begin in the Himalayas. Altogether, as many as 2 billion people depend on melting Himalayan snow and ice for survival.

The Himalayas also shape the region’s climate. They block the clouds! South of the range, moist air moves north from the Indian Ocean. When the clouds hit the Himalayas, they rise and cool. Cool air can’t hold as much moisture. Out comes the rain. It drenches the southern Himalayan slopes like a super soaker. Very little moisture makes it across the range. The windswept Tibetan plateau north of the Himalayas is dusty and dry.

The High Life

If clouds can’t even cross the Himalayas, how can people? The answer: Not easily!

For centuries, traders labored on the region’s steep, dangerous paths. They carried tea to Tibet, silk to Bhutan, and salt to Nepal. Herders used the trails, too, driving their wooly yaks to pasture and market. The traders, herders and yaks struggled over icy mountain passes and rickety bridges that spanned terrifying gorges. Along the way, they stopped to rest and pray at graceful religious monuments called stupas.

These days, roads and even trains cross some Himalayan passes. The Qinghai-Tibet railway is the world’s highest, climbing to over 16,600 feet. Still other routes are as rugged and risky as they were 500 years ago.

Despite the challenges, plenty of people live in the Himalayas. The biggest cities, such as Kathmandu in Nepal, Ladakh in India, and Lhasa in Tibet occupy valleys or plateaus. Smaller villages are scattered up to elevations of over 15,000 feet: nearly three miles above sea level!

The modern world has been slow to reach the people of these sky-high villages. Though a few residents even have the Internet, most meet the hardships of mountain life as they have for hundreds of years. They tend herds of goats, sheep and yak. With no wood in sight, they burn yak dung for fuel. The climate is bone-chilling. Sometimes melting glaciers unleash torrents of icy water that sweep through people’s homes and potato fields.

The Sherpa of Nepal are one group living this high life. Sherpas are known for their expert mountain-climbing skills and ability to endure extreme altitudes. They have climbed and guided other climbers since the first ascent of Mount Everest in 1953.

The Himalayas are not easy to live in. They aren’t easy to visit either. Yet, these high icy mountains draw adventurous visitors from all over. They come to meet Sherpas and others who live there. Some visitors just want to see the world from a new view. Others want to see it from the very top. These climbers hope to stand on Earth’s loftiest summits. Maybe someday you will too.

Written by Beth Geiger

[wp-simple-survey-35]