Rivers and the flowing waters that feed them have many names— creek, stream, brook, rill, runnel, rivulet, watercourse, And many individual rivers have nicknames too, such as “Big Muddy” for America’s longest river, the Mississippi. But whatever you call them, from the longest and strongest—the Amazon, Nile, and Yangtze—down to the smallest mountain creek, rivers are the lifeblood of the Earth.

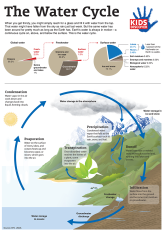

When rain falls or snow melts, it needs to flow. Taking the easiest route downhill, the natural flow of water carves channels in the landscape, forming a pattern that often looks like the branching of a tree. Drops of water seep into tiny rivulets, which run into larger waterways and eventually into rivers. All the rivulets, creeks, and streams that feed a river are called tributaries.

The area of land that feeds a river is called a watershed, or drainage basin. Whether you live in a city, on top of a mountain, in a valley, or even in a desert, every place on Earth is part of a watershed.

The world’s largest watershed (by far) is the Amazon Basin, which covers over 2.6 million square miles (40 percent of South America) and funnels water from over a thousand tributaries in eight countries. It all flows into the mighty 4,000-mile-long Amazon River, which has a phenomenally powerful flow. In fact, the Amazon carries more than one-fifth of all the river water in the world.

A river is always changing. One day it may be beautiful and peaceful, and another it may be overflowing with storm water and flooding surrounding areas. Rivers change along their course, too, with water moving faster or slower in different sections, and all kinds of mini-ecosystems forming—from deep pools to waterfalls.

However, all rivers share some traits. These are the key parts of a river:

Source: Big rivers are fed by many tributaries. But there is only one “source.” The source is the start of the tributary that is farthest upstream from river’s end. The source may be a spring, a pond, a melting glacier, or a marsh. The source is often high up in the mountains.

Channel: Flowing water cuts a channel, usually in the softest ground, for a river to run through. It can be wide or narrow, shallow or steep. Rivers don’t flow in a straight line, but twist and turn through the landscape, following the “path of least resistance.”

Riverbank: The land right next to the river, riverbanks are home to an ecosystem called the “riparian zone.” Plants growing in the riparian zone are especially water-loving. The dense vegetation on riverbanks is home to many species of animals.

Floodplain: Rivers don’t always stick to their channels. When snowpack melts up in the mountains or there’s a big storm, many rivers overflow their banks. The land around the river that periodically floods is called the floodplain.

Mouth, or delta: Here, the river ends. As it approaches its mouth, a river loses energy, slows down, and spreads out over a wider and wider area as it flows into a lake, ocean, or wetland. Sediment that’s been carried from upstream is deposited in the delta—and the nutrients from the sediment create healthy soil for plant growth.

Rivers have always carried the drinking water that’s essential for human survival. Even today, two-thirds of all our drinking water comes from rivers. But rivers carry more than water. They are conveyor belts for nutrients that make soil good for growing food. In fact, without rivers, human civilization may never have gotten started.

Until 12,000 years ago, humans were nomads. We travelled around from place to place, hunting animals and gathering edible plants. But our growing relationship with rivers made us change our wandering ways.

When a river naturally floods, it deposits silt full of nutrients in its floodplain. It was in the rich riverside soils of Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China that ancient people first began to practice agriculture, farming the land and growing crops. Once we grew enough food so that we no longer had to travel to find it, we could build settlements—and human civilization truly began.

The first agricultural settlements were in Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and along the Nile River in Egypt. The natural flooding of the rivers provided both fertile soil and water needed for growing crops. But floodwaters could also be dangerous. If the ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians weren’t careful, their homes in the floodplain could be swept away.

That’s why many of the world’s earliest inventions involved controlling the natural flow of water. The Mesopotamians dug canals and artificial ponds to re-direct floodwaters and save their settlements from destruction. Then, from the canals, they dug smaller irrigation ditches with gates that could be opened and closed to bring the correct amount of water to their crops.

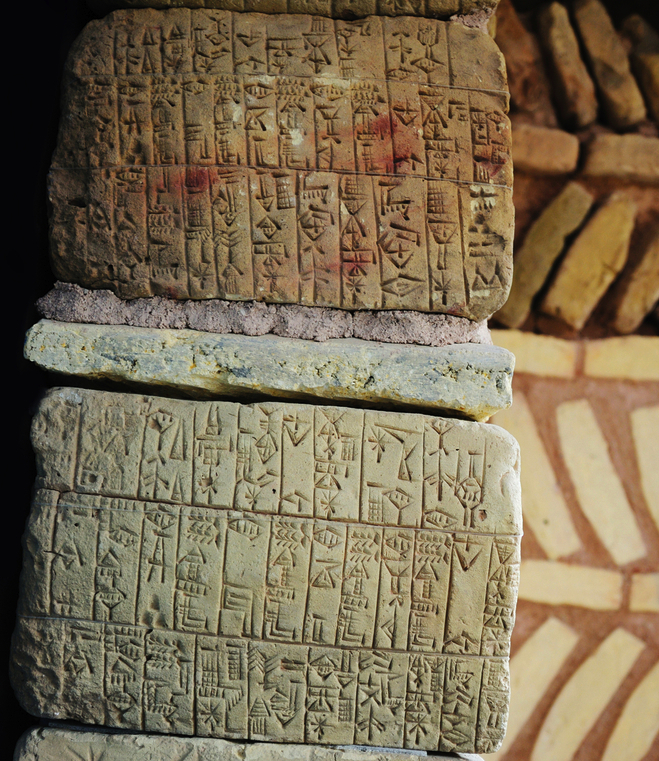

Rivers provided ancient people with other resources, too. When Mesopotamians developed the first writing system, the rivers gave them their writing tools. Natural clay was plentiful thanks to the deposits of wet muddy silt—and the people used this river clay to mold tablets. They pressed symbols into the soft clay tablets using river reeds for styluses.

Rivers are nature’s roads, and until trains, trucks, and planes were invented, they were the best way to travel. Many modern cities were founded on the banks of rivers so that goods could be transported from town to town. In addition, during the early Industrial Revolution, many towns and textile mills were founded on rivers so that the flow could be used to turn water wheels that ran mills and their machines.

In the 19th century, paddle-wheel steamboats ran regularly up and down the Mississippi River. Today, the historic Delta Queen still carries passengers. (Spirit of America / Shutterstock)

Civilizations have been tapping into the flow of water for thousands of years—using it for irrigation, transportation, and mechanical power. But it wasn’t until the late 1800s that engineers came up with the idea of harnessing the energy of rivers to generate electricity.

About one-sixth of the world’s electricity is generated by hydropower plants—dams built on rivers that use the flow of water to spin turbines and create an electrical current. The energy from dams is “clean”—with no dangerous air pollutants or greenhouse gases emitted.

However, the construction of dams and resulting change in water flow can hurt the river environment. New dam construction projects are often controversial.

Over 700 feet high and weighing more than 6 million tons, the Hoover Dam allows engineers to regulate the flow of the mighty Colorado River. What’s the purpose of changing the flow? The dam helps stop damaging flooding of agricultural land further downriver, stores water for the irrigation of crops and for use in homes, and it’s also attached to a power plant. The river water turns turbines and generates electricity for 8 million people.

Rivers are some of the most biodiverse places on the planet. But they are also areas of intense human activity—which unfortunately can bring both habitat destruction and pollution.

Written by Margaret Mittelbach

[wp-simple-survey-33]