“Friends! Brethren! Countrymen!–That worst of plagues, the detested tea, shipped for this port by the East India Company, is now arrived in the harbor.”

The day the colonists dumped thousand of pounds of tea into Boston Harbor turned out to be one of the most important in American history. Dubbed the Boston Tea Party, this act of protest was both defiant and illegal. It sent a message to the British government that the colonists were fed up with unfair treatment—and it lit the fuse that ignited the American Revolution.

So what in the world was so important about tea?

In colonial times, Boston was the capital of the Massachusetts Bay colony, one of the original thirteen American colonies. About 16,000 people lived there, making Boston one of the biggest colonial towns and most important ports. Boston’s shores were lined with wharves and warehouses. The winding streets were dotted with brick buildings—stores, workshops, newspaper offices, churches, meeting halls, homes, schools, and taverns.

Like all the colonies, Massachusetts was part of the British Empire. A royal governor appointed by the king was the head honcho in Massachusetts, but the colonists also elected their own assembly to pass local laws and set taxes. Although the colonists were allowed some self-government, they were subject to lots of restrictions under British law. For example, they were only allowed to trade goods with Britain.

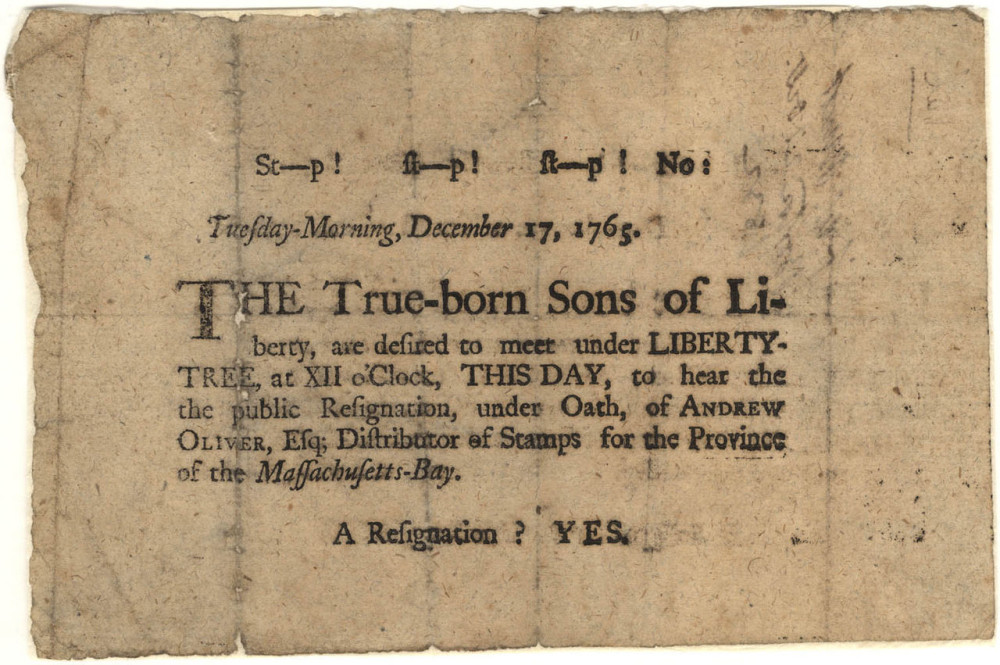

Under this system, the colonists pushed for more freedom and often the British government pushed back. In 1765, the British Parliament gave the colonists a particularly hard push, passing the Stamp Act, which required a direct tax be paid on every piece of paper used for printing in the colonies—newspapers, legal contracts, licenses, even playing cards. The colonists had never had to pay a tax like this before. And they were especially angry because they didn’t have any say in the matter. Even though they had their own local assemblies, the colonists weren’t allowed to elect representatives to Parliament.

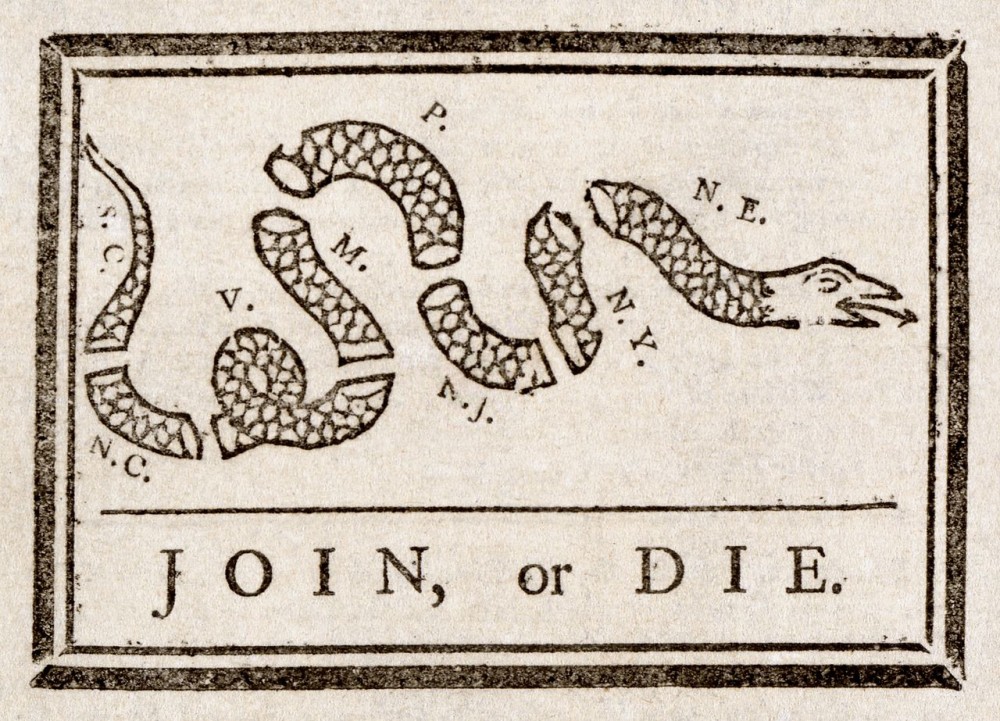

The colonists protested with the slogan, “No Taxation Without Representation,” and demonstrations against the Stamp Act sometimes led to violence, with tax collectors being physically intimidated.

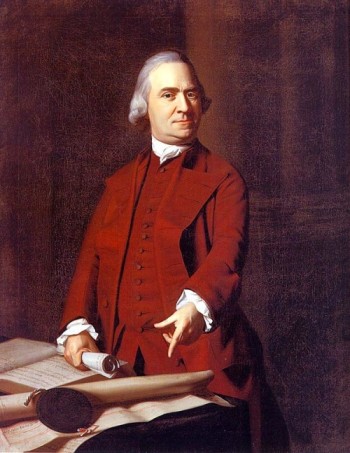

In Boston and New York, the Sons of Liberty was formed to organize formal opposition to the Stamp Act. Samuel Adams, a Boston politician, was one of the most outspoken leaders.

The Sons of Liberty organized meetings; wrote, spoke, and published about unfair policies of the British government; and organized secret “committees of correspondence.” These committees were devoted to informing other towns and colonies about protest activities in an effort to create unity between all the colonies. This idea spread until all 13 colonies had secret committees that opposed unfair British laws.

Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, but quickly replaced it with the Townshend Acts in 1767. The Townshend Acts required the colonists to pay import taxes—called “duties”—on glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea.

The colonists rebelled against these taxes by organizing boycotts. Since they couldn’t vote down the taxes, they would refuse to buy tea and the other items being taxed.

Drinking tea was a big part of people’s social lives in colonial America, so boycotting tea was actually a big deal. However, many colonists decided they would rather give up tea than give up their rights. Others drank untaxed tea that was smuggled into the colonies from Holland—also in defiance of British laws.

In response to the Townshend Acts, Samuel Adams wrote a protest letter about taxation without representation. The protest letter was circulated to the other colonies and adopted by the Massachusetts House of Representatives. To punish the colony for this protest, the British government ordered that the Massachusetts legislature be disbanded. This dramatically increased the tension, and the king sent warships and 2,000 troops to Boston to enforce the order.

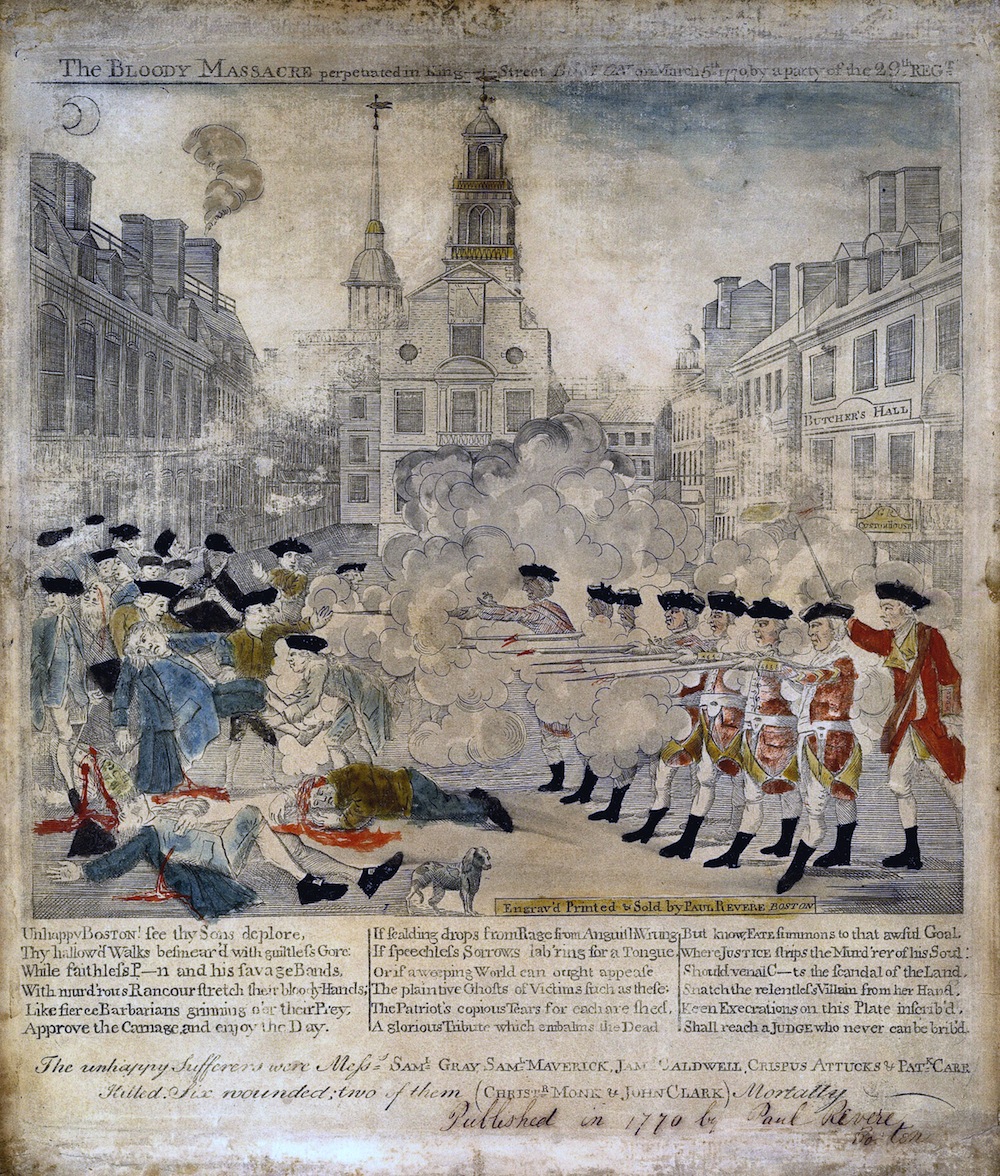

The people of Boston were not happy their town was occupied by a force of red-coated British soldiers. The tension grew until it finally exploded in violence on March 5, 1770. A crowd of angry Bostonians taunted and threw things at a small group of redcoats, and the soldiers shot at them, killing five Bostonians. This incident was dubbed the Boston Massacre.

Not long after the Boston Massacre, the Townshend Acts were repealed. Parliament stopped charging tax on most goods shipped to the colonies. But they kept the tax on tea, just to make sure the colonists knew that the members of Parliament and the King of England were still boss. And the British troops remained in Boston.

Parliament also passed the Tea Act in 1763. This created a tea monopoly, which made the colonists furious. The British East India Company was given the exclusive right to ship tea directly to the American colonies. Only a few hand-picked merchants in the colonies could sell the tea. And guess who the agents for the tea were in Boston? Yep, they were the sons of the colony’s royal governor and a few other loyalists.

Patriots in Boston demanded that these merchants give up their commissions to sell tea—and when the merchants refused, the patriots responded with threats. A Boston mob even attacked the home of one of the merchants. Meanwhile, the Sons of Liberty were meeting nearly every day to discuss the Tea Crisis.

On November 28, 1763, the Dartmouth, the first of three ships carrying tea for the British East India Company sailed into Boston. Late that night, a notice was posted all over town by the Sons of Liberty that read, “Friends! Brethren! Countrymen!–That worst of plagues, the detested tea, shipped for this port by the East India Company, is now arrived in the harbor.” The notice invited everyone to a big meeting in the morning.

The town meeting turned out to be epic. About 5,000 people from Boston and surrounding towns packed into the Old South Meeting House. The attendees called themselves the Body of the People. They voted that the tea should be sent back to England and they sent a guard to prevent the tea from being unloaded.

The meeting lasted for two days, and on the second day, the sheriff showed up with a proclamation from the royal governor. It stated that the people were “openly violating… the good and wholesome laws of the province.” They were ordered to “disperse and cease all further unlawful proceedings.” The Body of the People greeted the proclamation with hissing sounds and immediately voted to ignore the order to disperse.

Over the next few days, two more ships carrying tea sailed into Boston Harbor, the Beaver and the Eleanor. All their other cargo was unloaded, but the tea remained on the ships. And the ships remained in the harbor under guard.

Twenty days after the Dartmouth arrived was the deadline for paying the tea tax. The owner of the Dartmouth, Francis Rotch, was caught in the middle between the patriots and loyalists. The Body of the People wouldn’t let him unload the tea, but if he left the harbor with the tea still onboard, he worried the Dartmouth would be impounded by British warships—or worse that the ship would be fired on with cannons. Could he get a pass from the royal governor to take the tea back to England? On the morning of December 16, 1773, the Body of the People agreed to let Rotch make the attempt.

It took all day for Rotch to ride out to see the royal governor—and when he finally returned to the meeting, it was after dark. His trip had been a failure. The royal governor, he told the crowd, had refused to let the Dartmouth leave with the tea still onboard. Although the town meeting officially continued, there was a distinct change in the atmosphere.

Samuel Adams is said to have told the crowd, “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.” Some historians believe Adams’ statement was a signal to put a secret plan in motion. Within a short time, a group of men dressed up as Mohawk Indians walked passed the meeting house and several attendees followed them. The men carried axes, wore feathered bonnets, and had covered their faces in coal dust so that they could not be recognized.

They walked down to the wharf where the tea ships were docked. Although we call this event the “Tea Party” today, it wasn’t considered a party then—it was dead serious. The participants knew they were breaking the law and defying the king. They swore an oath of secrecy about their participation, because if anyone found out who they were, there would be serious consequences.

What happened next was peaceful and smoothly executed. About 100 people in disguises boarded the three ships. Over the next three hours, 342 crates, holding 90,000 pounds of tea, were removed from the ships’ holds and broken open with axes. The loose-leaf tea in the crates was then dumped into the harbor. Many years later, one of the participants said they had made a “giant cup of tea for the fishes.” None of the ships was vandalized or damaged—and after the tea was dumped, the participants melted back into the night.

What was the British response to the Boston Tea Party? The British government passed a series of laws meant to punish and control the colonists. These laws were called the “Coercive Acts” by the British and the “Intolerable Acts” by the colonists.

The first of these laws was the Boston Port Act, which ordered the shut-down of Boston Harbor until the entire cost of the dumped tea was re-paid to the British East India Company. No ships or goods could go in or out of the harbor, leaving Boston cut-off from supplies.

The other coercive acts put even more restrictions on self-government in Massachusetts and demanded that the colonists provide quarters for British soldiers—in private homes if necessary.

The colonies swiftly united against the Coercive Acts. Within a year, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia with delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies, including Samuel Adams from Massachusetts.

All this—inspired by the Boston Tea Party—lit the fuse leading to the American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence.

Written by Margaret Middlebach

[wp-simple-survey-45]