Using Primary Sources to Drive Class Discussion

- February 23, 2016

- By Justin Birckbichler

In our present day world of education, classroom instruction revolves around being future-ready and effectively implementing the latest technology. However, in my most recent Civil War unit, I surprised my fourth graders by saying that we were putting our Chromebooks away for the entire unit. In response to their shocked faces, I explained that we were going to be historians and travel to the past, through the exploration of primary sources.

Primary sources are documents, artifacts, recordings, and other material that were created during the era that we studied. (A letter written by Lincoln would be a primary source, while a documentary about him would be a secondary source.) According to the Library of Congress, primary sources help achieve higher levels of engagement, critical thinking, and knowledge construction.

To be perfectly honest, I had a hard time believing this at first. I felt that primary sources were boring, tedious, long, and too advanced for elementary students. However, I encountered a paradigm shift after attending an educational weekend retreat at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Many of the breakout sessions revolved around using primary sources in the classroom. We learned that you can use parts of the entire document (which was a moment of epiphany for me) and various ways to make it more interactive and engaging. Furthermore, many primary sources have been transcribed into typed versions. The debate about cursive rages on in the field of education, but I think we can all agree that this helps our students read the writings of our forefathers.

While my students interacted with the primary sources in a non-digital format, I relied heavily on digital methods to gain access to primary sources. I used the archives of the Library of Congress and the Civil War Trust for most of my unit, but there are numerous websites for various eras of history. I organized them all into a Google Doc for ease of access and printed hard copies of the documents for the students. I could have shared the Doc with the students to access the various links, but there is just something awe-inspiring about actually holding the source to analyze it.

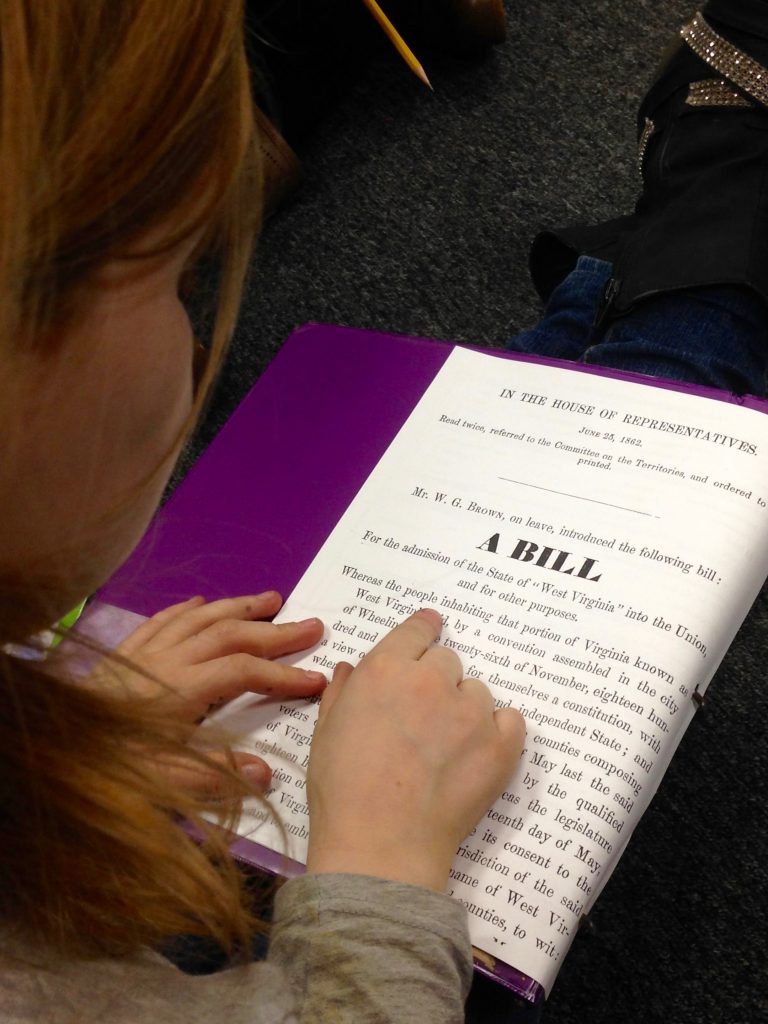

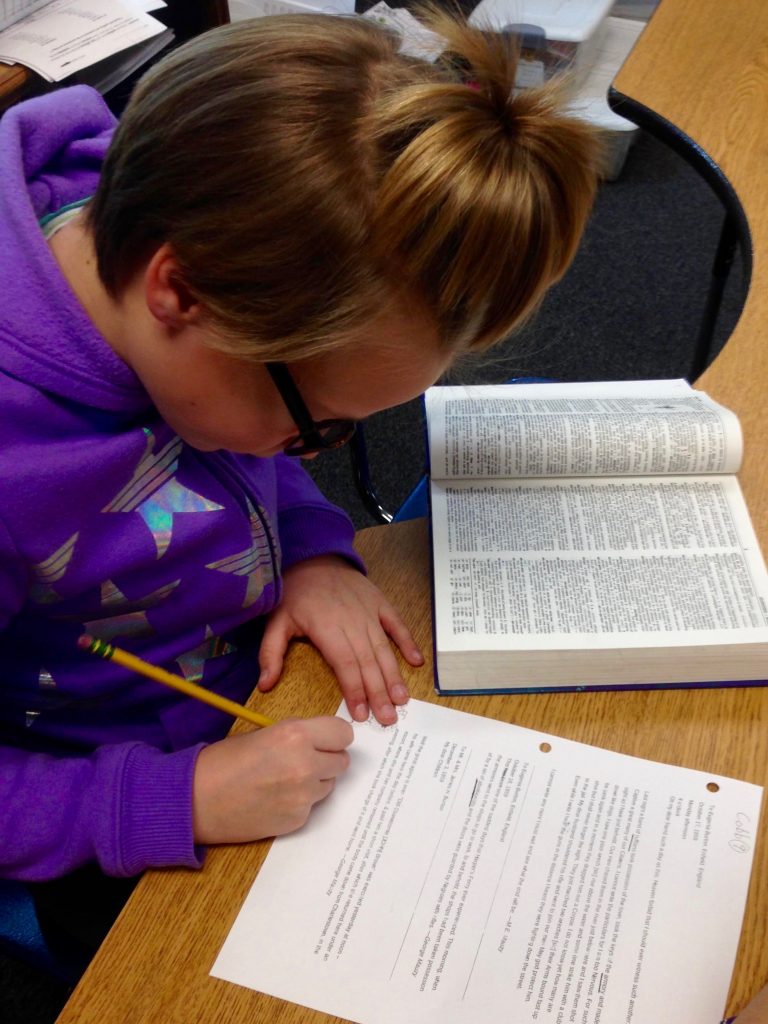

By the end of the unit, my class of little historians had analyzed personal letters, newspapers, congressional bills, paintings, artifacts, and other documents, all from the 19th century. I would give them a brief overview of the document, remind them of analysis procedures, and turn it over to them.

When they convened in their groups, they were given the appropriate analysis tool from the National Archives. These tools are similar to the tools that actual scholars use when they encounter a new primary source, but have been adapted for use in the classroom. These tools can be used online or on paper copies. My students ate up the experience of being historians, one saying, “I liked that we were able to discover our own learning rather than you telling us” and another proclaiming, “It makes you feel like you’re living in 1861.”

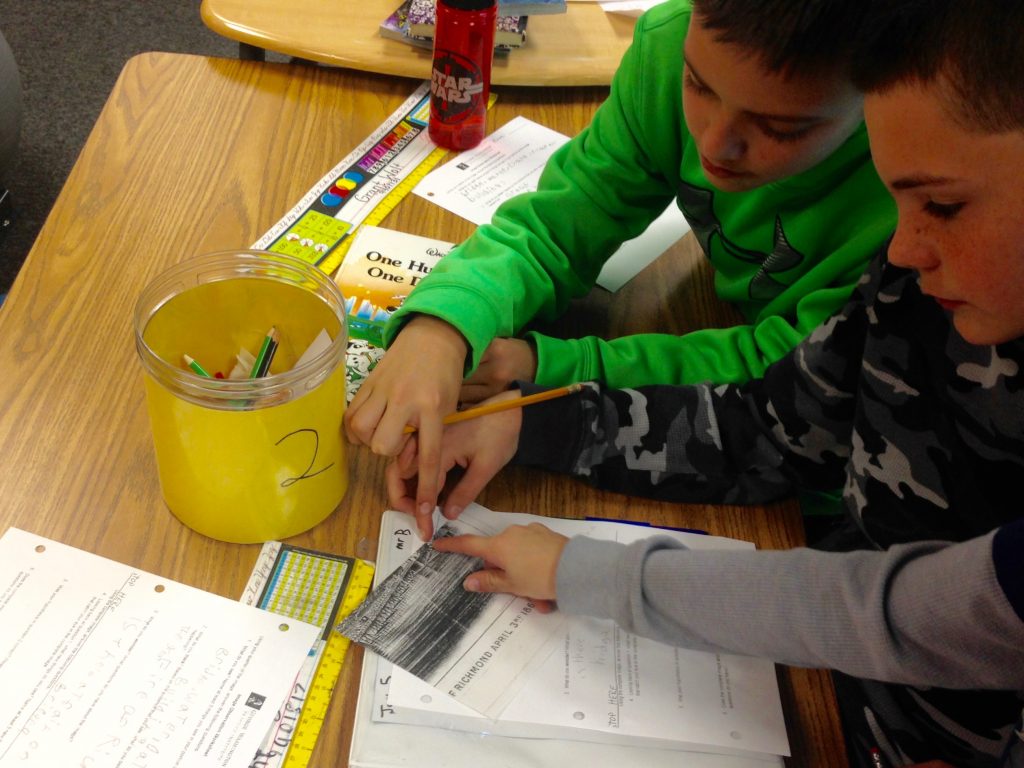

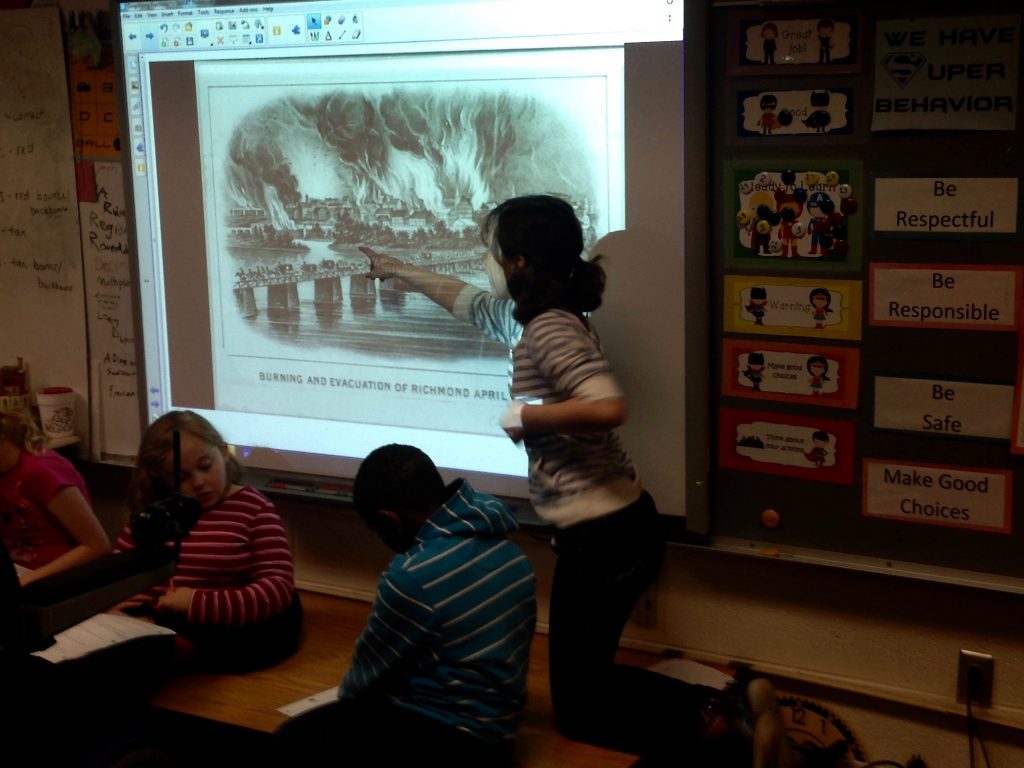

One favorite activity was cutting a scan of the painting of the burning of Richmond into six parts and giving a different part to each group. Using their one piece, each group made inferences about the event the entire painting detailed. Gradually, we revealed the entire painting, which gave them various degrees of accuracy in their predictions.

I was very impressed with their discoveries, too. Many of the analysis tools include a section asking the students what further questions they have about the event portrayed in the source. In nearly all cases, the questions they developed led to the main focus for the day’s lesson. For example, when we read the bill admitting West Virginia to the Union, they asked why West Virginia had become a state.

Contrast that to if I had just stood at the front of the room and told them that West Virginia became a state because it opposed slavery. They developed the question and our conversation flowed from there. The lesson took longer than in previous years, but their connections to it are deeper now.

That’s my main takeaway from our work with primary sources – they may not exactly cover the prescribed curriculum, but they will lead to engaging discussion that will. There was never an instant that the primary source didn’t unveil the reason for the lesson or spark a discussion that did. My students feel that they were “really there with them,” could “understand better because you can actually read their facts,” can “understand more about the past,” and could “learn a lot about some people.”

Besides, who better to teach us about the past than those who lived through it?