A dense band of stars glitters across the night sky. It’s an edge-on view of our own Frisbee-shaped Milky Way Galaxy. The Milky Way contains hundreds of billions of stars.

Just imagine: any of those stars could have planets circling it, just like Earth. Could something—someone—be alive out there?

Eye In The Sky

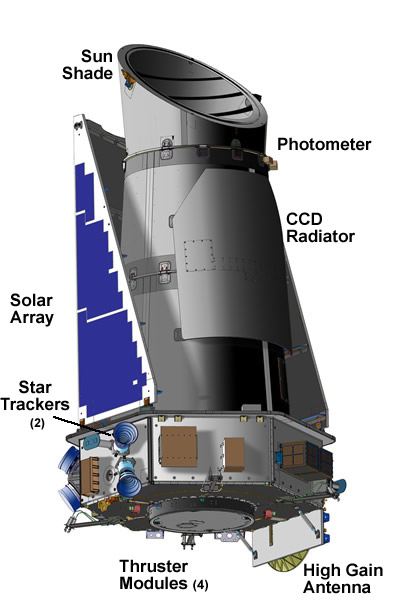

We may finally find out. In March 2009, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) launched a spacecraft called Kepler. Kepler is the first NASA mission designed to search for habitable exoplanets. An exoplanet is any planet outside of our own solar system.

Kepler is a big telescope mounted on a little spacecraft. The telescope is over three feet (0.95 meters) across—the largest camera ever launched into space. When it comes to hunting for exoplanets, Kepler is our big eye in the sky.

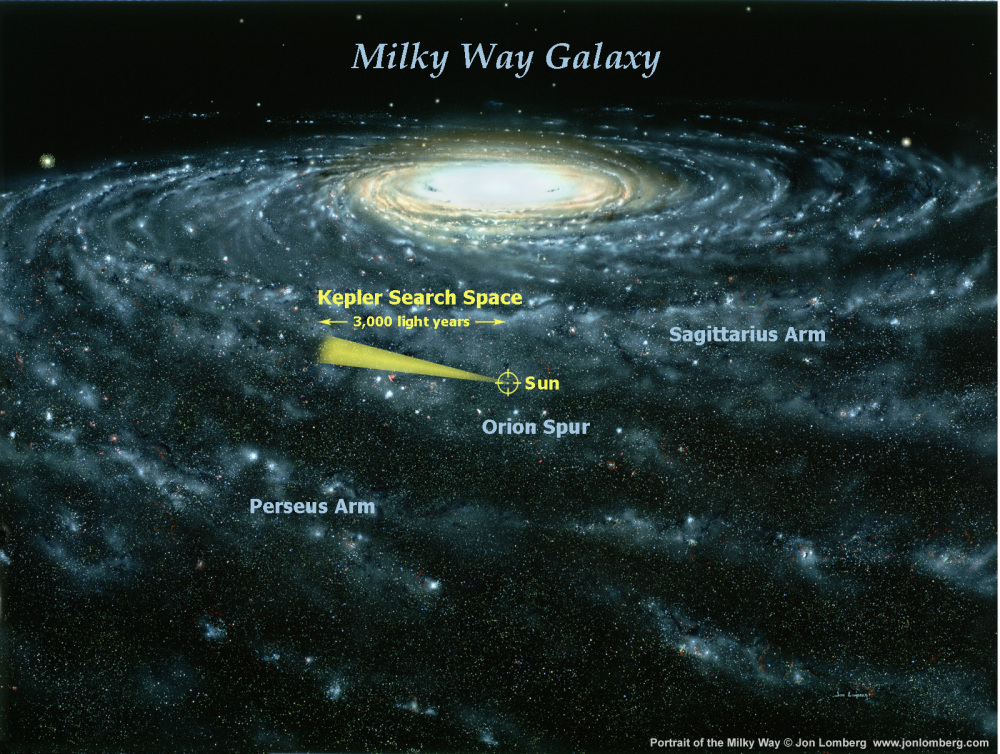

Kepler’s first mission lasted four years, until April 2013. All that time, it pointed to the same part of the Milky Way, a region around 500 light years from Earth. That’s unimaginably far. Just one light year is almost 6 trillion miles!

Astronomers zeroed in on that part of the galaxy because it has so many stars. That increases the chances of finding something. “Kepler watched 150,000 stars at once,” says Steve Howell, Kepler Mission scientist.

Kepler’s second mission, called K2, began in April 2014. K2 is still going on. This time, Kepler watches a closer part of the galaxy, for just three months at a time.

Sweet Spot

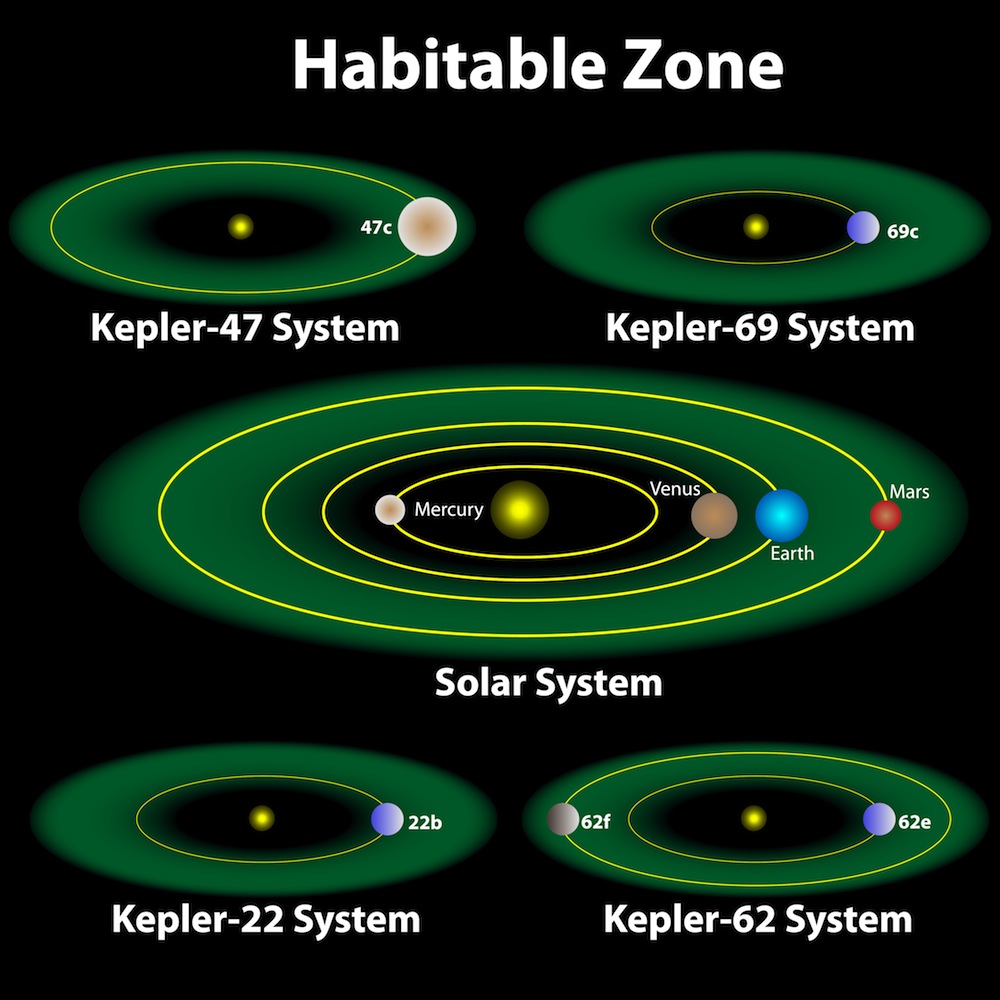

Even though Kepler is powerful, there’s no way it could spot signs of life from so far away. Instead, Kepler looks for exoplanets that might be habitable. Habitable means having liquid water.

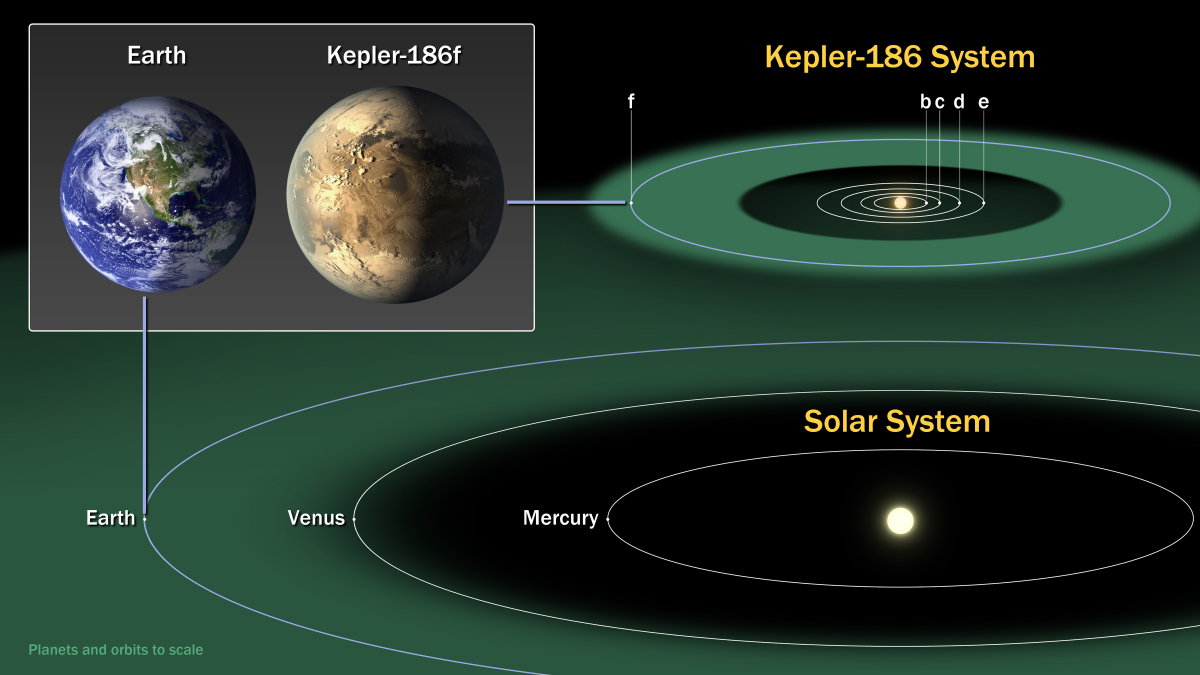

Earth orbits our sun at just the right distance to have liquid water. We are close enough not to be frozen. We are not so close that our water sizzles away. You could say that Earth is in a real sweet spot. Astronomers call that sweet spot the habitable zone.

Size matters, too. In our solar system the giant planets, like Jupiter, are gassy. Who could hang out on a pile of gas? It’s the smaller planets that are nice and rocky.

But too small, and a planet won’t have a strong gravity field. Gravity is what keeps Earth’s atmosphere from floating away. Our atmosphere, in turn, keeps Earth’s water from disappearing. “If you took away our atmosphere our oceans would boil away,” says Howell. The perfect planet would be right around Earth’s size, and rocky like us.

Not too hot. Not too cold. Not too big and gassy, and not too small. Just right. No wonder planets in the habitable zone are nicknamed Goldilocks planets, after the picky little porridge eater.

Planet Finder

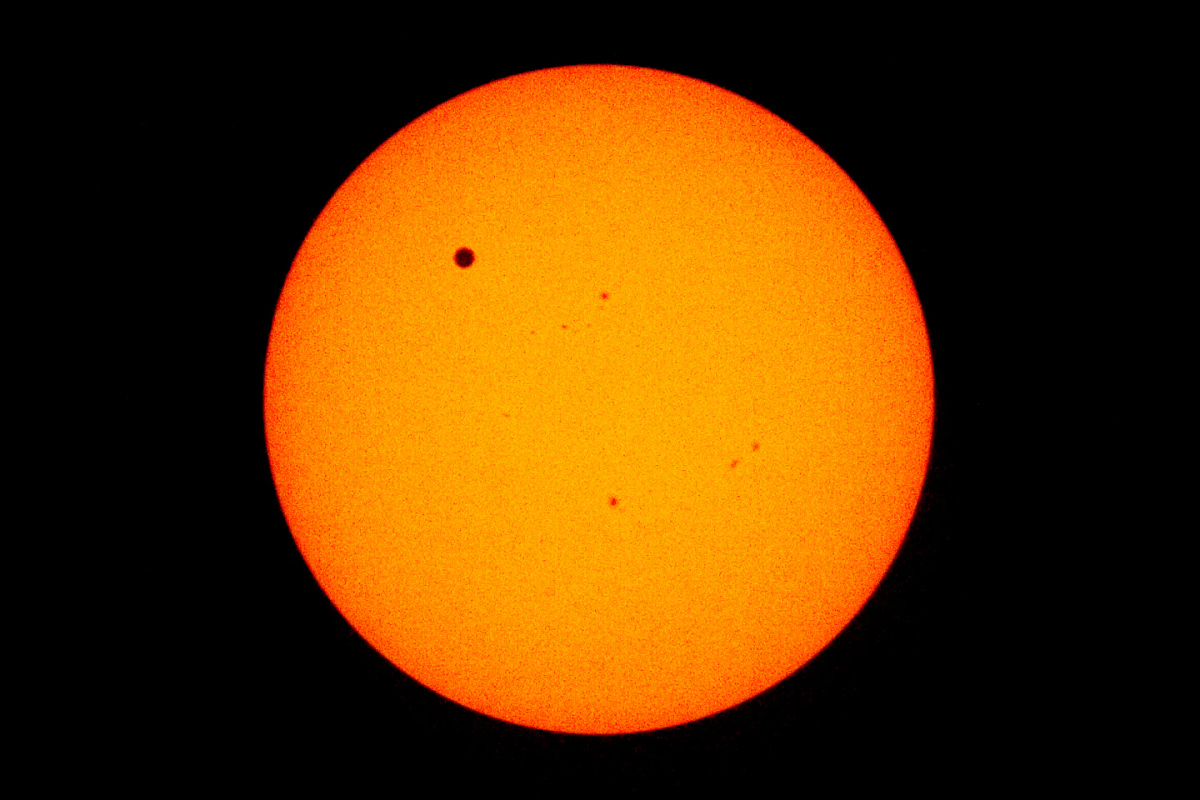

How on Earth does Kepler search for a just-right planet trillions of miles away? Kepler’s secret is an out-of-this-world ability to detect changes in stars’ brightness.

When an orbiting object passes in front of a star, it appears as a tiny moving spot. That pass is called a transit. Each transit blocks out a tiny amount of the star’s brightness. The change is incredibly small: it only dims it by about 1/10,000th . But spotting transits are what Kepler lives for. It can measure that minuscule difference.

Of course, a spot might not be a planet. It might be another star, or even a speck on the telescope, says Howell. To be sure a transit really is a planet, Kepler must see it repeated on a regular schedule, the way Earth orbits the sun once every year. That’s why Kepler watched the same stars for four years. It has to catch at least three transits to be sure.

Even harder, transits also only appear from just the right viewpoint, and for a short time. “Only one percent of planets show using the transit method,” says Steve Howell. That’s why Kepler doesn’t “blink.” “Look away, and you might miss the transit,” Howell said.

If it is a planet, is it in the habitable zone? To find out, astronomers measure the temperature of the star by analyzing the light coming from it. Then they use data from Kepler to determine how far the planet is from its star. If the distance is just right, it might be in the habitable zone: a Goldilocks planet,

Alien Worlds

Kepler’s discoveries are as out-of-this world as its technology. “When Kepler was launched the known number of planets outside our solar system was zero,” Howell told Kids Discover. Kepler has already found thousands. “Planets are everywhere!” Howell says. Altogether, Kepler has found almost 1,000 confirmed exoplanets.

The first exoplanets Kepler discovered would make Goldilocks run for home. Too big and too hot: 2200 to 3000 degrees Fahrenheit. Kepler has found Earth-sized planets, but most are too hot, too.

One discovery will thrill Star Wars fans. Remember Luke Skywalker’s home planet Tatooine? It had two-suns. Kepler has found at least 20 real planets that orbit two suns. No sign of Luke, though, since none are hospitable to life.

Now the news you’ve been waiting for. In April 2014 NASA astronomers announced that Kepler had found the first Earth-sized planet orbiting in the habitable zone of a relatively cool, small star. This cozy little planet, called 186f seems to have it all. Based on its size, Howell says it is highly likely that 186f is rocky like Earth.

Next Up?

By finding so many new planets, Kepler has set the stage for more discoveries. In 2017 NASA will launch a new mission called TESS. TESS stands for Transiting Exoplanet Surveying Satellite. “TESS will also look for transits, at stars that are brighter and nearer to us,” says Howell. Then, in about 2018 the James Webb telescope will be launched. It will be able to tell if a planet has an atmosphere, and what the atmosphere is made of. That’s another big step towards finding extra-terrestrial life.

We won’t be visiting these new worlds any time soon, says Howell. “But some of the stars found during K2 will be close enough to imagine communicating with,” he says. The real question is, if we wave, will anyone wave back?

Written by Beth Geiger

[wp-simple-survey-40]