Think about all the different things people do for work and money all around the world. Think about all the things that people are buying and selling. The world economy is constantly in motion.

Economics covers everything from how much you charge for lemonade at a sidewalk stand to how big and small businesses operate to how whole countries pay for things like roads and bridges.

At its most basic, economics is about making and using goods and services—the things people want and need.

Goods are physical things, such as apples, toys, clothes, toothpaste, computers, and cars. Most goods cost money, but some (like the air you breathe) are free.

Services are jobs done (mostly) by people. Doctors, fire fighters, hair stylists, and bus drivers all provide services that people want and need. Sometimes services are provided by animals, such as seeing-eye dogs. Services can also be provided by nature. For example, rain is an “environmental service” that provides communities and farms with water.

Pizza companies sell a combination of goods and services. The pizza is a “good.” Delivering the pizza to your door is a “service.” (Kalmatsuy / Shutterstock)

Pet grooming is a service. In the United States, nearly 100,000 pet grooming businesses make a total of about $5 billion a year. (Siamionau Pavel /Shutterstock)

So what should you do if you want to produce a good or service and sell it? First of all, you need resources. Resources are the inputs you need to make products. There are three main different kinds:

- Natural resources: This includes things like land, trees and forests, rivers and oceans, coal and crude oil, sunlight, and wind, gold and silver, copper and iron, wild fish and shrimp

- Human resources: Miners, farmers, construction workers, store clerks, teachers, and entertainers—you name it! People are a powerful resource, and so is the knowledge that people acquire and bring to a task. All the working people in the world are the world’s labor force.

- Material and financial resources: “Material resources” are things you need to make your product (such as ingredients for making a cake or tools for building a house). The term “financial resources” is a fancy way of saying you might need money to pay for supplies and labor to help make your product.

The stone at this quarry is a natural resource. The machines used to dig it out are material resources. The people operating the machines are human resources. (Alessandro Colle / Shutterstock)

Imagine your product is going to be lemonade sold at a lemonade stand. Lemonade is a “good.” Selling your lemonade at a stand is a “service.”

Some resources you would need to make and sell lemonade include the ingredients (water, lemons, and sugar), a pitcher or two, a mixing spoon, cups to serve the lemonade, a table to set up your stand, a person to make and sell the lemonade, paper and markers to make a sign, and change for customers.

What would you charge for a cup of lemonade? What is a fair price? How much will customers be willing to pay? How do prices and money work exactly?

In ancient times, there was no money. If people wanted something they couldn’t make, grow, do, or find themselves, they had to trade, or barter. A dairy farmer might barter with a horse-cart driver for a ride into the town. The farmer had extra eggs and milk to trade, but no transportation. The driver could easily get from place to place, but he needed food. How many eggs or jugs of milk was the ride worth? The farmer and driver had to negotiate and agree on a fair exchange.

A woodcut from the 1500s shows Nordic traders bartering with Russians, trading fish and blades for furs and other items. (Wiki Commons / Public Domain)

Of course, forms of bartering are still around. You’ve probably traded and negotiated with your friends—cookies for a sandwich, using a bike in exchange for homework help. But imagine if you had to barter for all the things you wanted. Just getting the ingredients and supplies to make lemonade would take soooooo looooooong. And what would you be willing to accept in trade for each cup of your lemonade? The economy would slow to a crawl.

Money was invented to make trading easier. At first, communities would agree that certain objects—such as specially carved beads or lumps of silver—could be used for trading and be recognized for their value. Slowly, money evolved to look a lot like it does today: coins and bills.

- About 4,000 years ago in China, people used small shells for money and the first metal coins in China were shaped like shells.

- The first official currency was invented in the kingdom of Lydia around 600 BC. The king of Lydia had silver-and-gold coins made and stamped with a lion’s head. This form of currency was copied by the neighboring empires and kingdoms in Greece, Macedonia, and Persia, where metal coins were stamped with the heads of ancient gods, emperors, and their symbols.

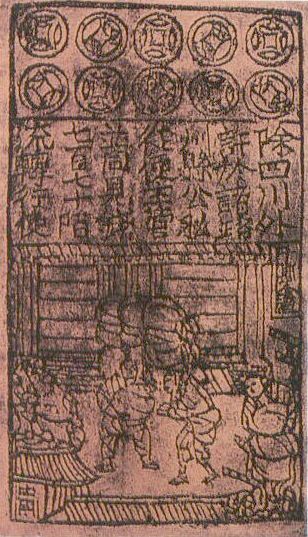

- After a while, all those metal coins got to be pretty heavy to carry around. The first official paper money was issued in China around 900 AD.

From about 400 BC, this ancient silver coin from the Greek city-state of Thebes has the god Dionysus on the “heads” side and the shield symbolizing Thebes on the “tails” side. The coin is a “stater,” which had a standard weight of 8.6 grams. (Wiki Commons / Public Domain)

A “jiaozi” from the Song Dynasty in China, this bill is an example of the world’s oldest paper money. (Public Domain)

A currency is the form of money used in a particular country. The currency in the United States it the U.S. dollar. In Japan, it is the yen. In Mexico, the peso. Every country has its own currency. Today, in the United States there is a total of about 1.3 trillion dollars in circulation, or flowing through the economy. That may sound like a HUGE amount. But it IS limited. The U.S. government issues paper money and limits the total amount of dollars in circulation.

When people started using money instead of bartering, trading soared. The word “currency” comes from an old word meaning “flow.” And that is a good description: Bartering is slow. Currency makes trading flow.

With money as a form of exchange, the whole world is a marketplace. People are making, buying, selling, and trading all the time. Trillions of dollars, yen, euros, pesos, and other currencies are exchanged every day.

Hello, George Washington (and friends)! These bills, also called banknotes, show the colorful currencies of several nations. (Bjorn Hoglund / Shutterstock)

The average lifespan of a dollar bill is six years. After spending time in circulation—in wallets, crumpled up in pockets, in cash registers and bank drawers—a dollar ultimately gets returned to the U.S. Federal Reserve for shredding. New dollars are printed to replace old dollars and to keep up with the demand for cash. (Sharon Day / Shutterstock)

One of the largest indoor markets in Mexico, the Mercado San Juan de Dios has three levels and nearly 3,000 stalls for selling goods. (Wiki Commons)

This is a market, too. On the “floor” of the New York Stock Exchange, shares in companies (stock) are bought and sold. About $170 billion is traded every day. (Photo: Ryan Lawler)

If you have money, you can spend it on goods and services. Or you can save it for later. Money does more than make trading flow. Money helps make it easier for people to save for the future and build wealth. Money and wealth can be passed along from one generation to another. Money can be invested in businesses or public projects. It can also be donated to charity.

If you had money to invest, what would you invest in? Some people build their own businesses. Governments sometimes invest money to build projects called “public goods.” Bridges, roads, and public school buildings are examples of “public goods.” (Taras Vyshyna / Shutterstock)

Most people get their money from working. The amount of money they make each week or month is called income. People and families use their income to pay for food, a place to live, clothes, transportation, taxes, and much more. If you were in charge of the money in your house, how would you spend it? What choices would you make?

One of the most important ideas in economics is this: You can never get everything you want. Money, time, “stuff” and resources are all limited. Nothing is unlimited. That means you have to make choices.

If you were in charge of your family’s income and decided to spend it all on video games and vacations, you wouldn’t have enough left for food. Eek! Making a plan about how to spend your income is called making a budget.

Decisions, decisions. One thing economists study is how people make choices. (PathDoc / Shutterstock)

Most families have a weekly budget for groceries. They only have a certain amount of money to spend at the market. What groceries do they choose to buy? What groceries do they choose NOT to buy? What strategies can they use to get the best possible combination of groceries AND keep within their budget? (Lisa S. / Shutterstock)

Let’s get back (finally) to your imaginary lemonade stand and what price you should charge for a cup of lemonade. Prices are based on supply and demand. Supply is a measure of how much there is of a good or service. Demand is a measure of how much people want or need a good or service. Here is how supply and demand would affect prices at to your lemonade stand:

Medium Supply/Low Demand: If you set up a lemonade stand on a snowy winter day, even five cents a cup might be too much. You might not be able to give away your lemonade, because no on wants or needs it. There is a supply of lemonade, but there is no demand.

Medium Supply/Medium Demand: BUT on a hot summer day, people are thirsty. They want lemonade! The demand for lemonade goes up in summer and so does the price. If you’re the only lemonade stand around, you might be able to charge $1 a cup. Cha-ching!

Medium Supply/High Demand: Is your lemonade especially good? Are all the neighbors recommending it? Maybe the demand is so high that you can charge $2! Double cha-ching!

High Supply/Medium Demand: Uh-oh. It’s summer and the kids across the street just set up their own lemonade stand. They are only charging 50 cents, and now all the neighbors are heading over there for lemonade. Due to the sudden increase in the lemonade supply, you may need to lower your price.

How are prices set? What if these kids wanted to charge $10 for a cup of lemonade? Would anyone pay that much? Would you? (Rob Marmion / Shutterstock)

Prices can go up and down. Businesses can have good years and bad ones. National economies can go boom and bust. It’s not always easy to predict what will happen in the economy. But in a world filled with choices, learning about economics can help you make better choices for yourself, your family, your community, and your future.

Written by Margaret Middlebach

[wp-simple-survey-42]