The Renaissance was an explosion of ideas, education, and literacy. It produced some of the greatest artwork and artists in history. The leaders of the Renaissance were born in Italy’s independent city-states and drew inspiration from Ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Even today, the buildings and streets of Rome, Florence, and many other Italian cities are filled with stunning Renaissance art and architecture. Famous Renaissance paintings hang in museums all over the world. The word “renaissance” literally means “rebirth.” In truth, the Renaissance gave birth to the modern world.

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome is one of the most famous artworks of the Renaissance. (Image via Wikipedia)

The Italian Renaissance was a reaction to life during the Middle Ages. In the Middle Ages, very few people knew how to read. Books were rare—and most were written in Latin, which was not a language spoken by everyday people.

The Renaissance got its start when a group of writers and scholars in Italy began to seek out the knowledge of classical Rome and Greece. These Italians looked back on Ancient Greece and Rome (the period from about 400 BC to AD 476) as a time when literature, philosophy, art and architecture all flourished. Starting in the 1300s, this new group of writers and scholars began calling themselves “humanists” and they referred to the Middle Ages—the time in which they were living—as the “Dark Ages.” They thought knowledge, education, culture, and innovation were not thriving in their own times. To bring back the “light,” they sought out, re-discovered, and studied books written in Ancient Rome and Greece. They wanted to relight the fire of intellectual and civic life that they believed had been snuffed out since the fall of the Roman Empire.

The School of Athens painted by Raphael in about 1509 typifies what the Renaissance was all about. The humanists looked back on ancient Greece and Rome as a time of cultural advancement and artistic achievement—and they wanted to bring the “light” of those times into their own age. With the ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle at the center of the action, the School of Athens pictures numerous philosophers reading, writing, listening, and discussing. This demonstrates some key beliefs of the Renaissance humanists—that society should pursue knowledge and education, that ideas both old and new are worthwhile and exciting, and that public debate is important. (Image via Wikipedia)

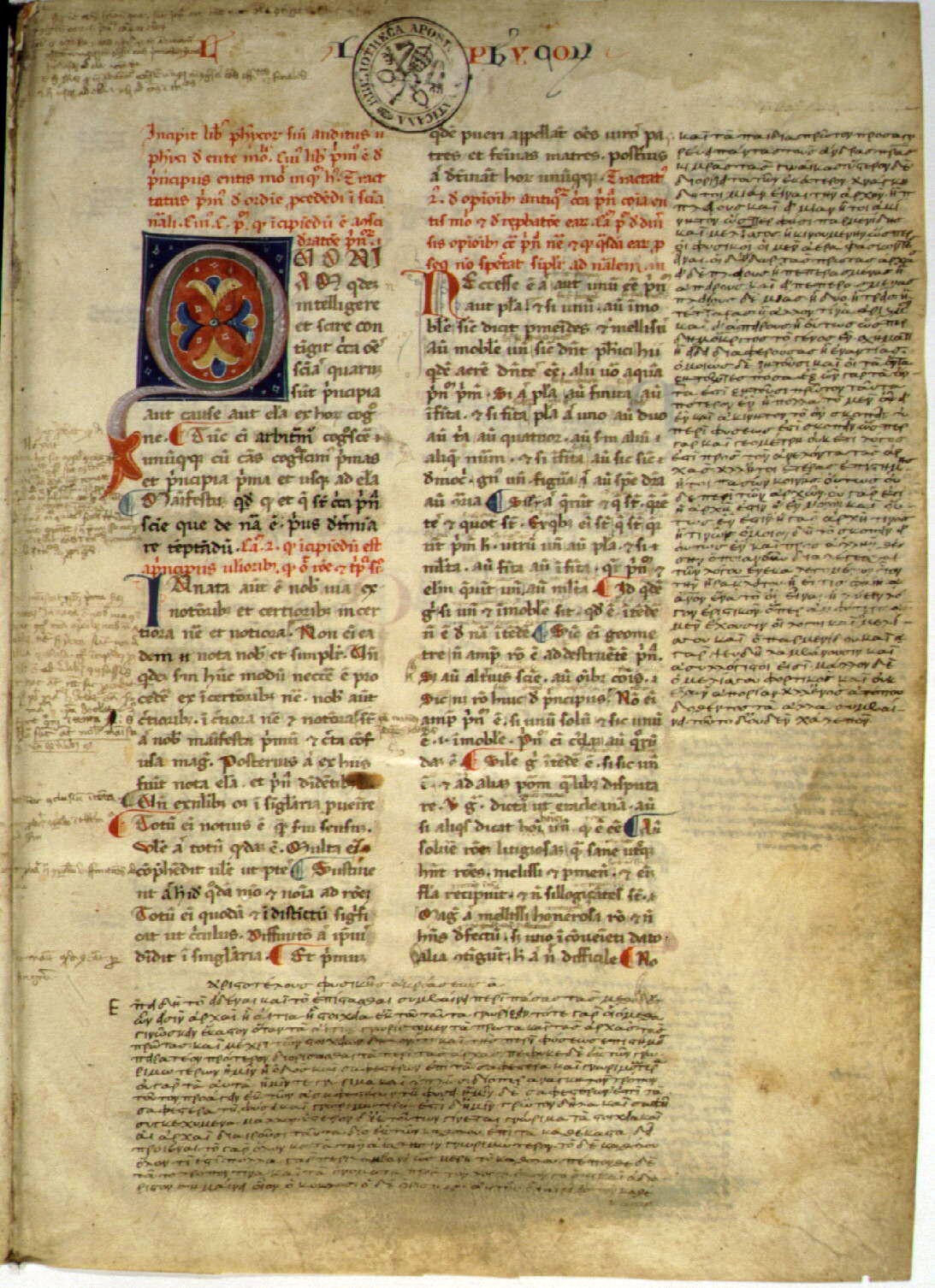

Although the authors of most of these ancient Greek and Roman books had been dead for over 1,000 years, their writing survived in the libraries of Europe’s monasteries. For centuries, monks had been making copies, writing out every word of the ancient texts by hand. Not too many people had read these books during the Middle Ages, but they were there when the humanists went looking for them. Inspired by the ideas, stories, and beautiful poetry of the ancient Greek and Roman writers, humanists began writing new works of literature in Latin (which they studied) and the “vernacular,” the language that people spoke every day.

A handwritten copy of The Physics by Aristotle was preserved and probably re-copied in the Middle Ages. The main text is written in a Latin translation, but a second scribe wrote out the original Greek in the margin. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

One of the early humanists was Giovanni Boccaccio. In 1348, a gruesome disease called the bubonic plague struck Boccaccio’s hometown of Florence, Italy. The “Black Death” swept through Florence and on through Europe, killing tens of millions of people. Boccaccio survived, and the real-life plague became the background for his most famous book, The Decameron. In it, Boccaccio writes a realistic account of the plague and then a fictional story about seven women and three men who flee the city and spend two weeks passing the time telling stories. The 100 stories that the characters tell became wildly popular. One reason for their popularity was that they were written in Italian, not Latin, so more people could read them. Even so, new books still had to be produced by hand, with scribes writing out every line. That strongly limited the number of books that could be produced. But as the Renaissance progressed, all that was about to change.

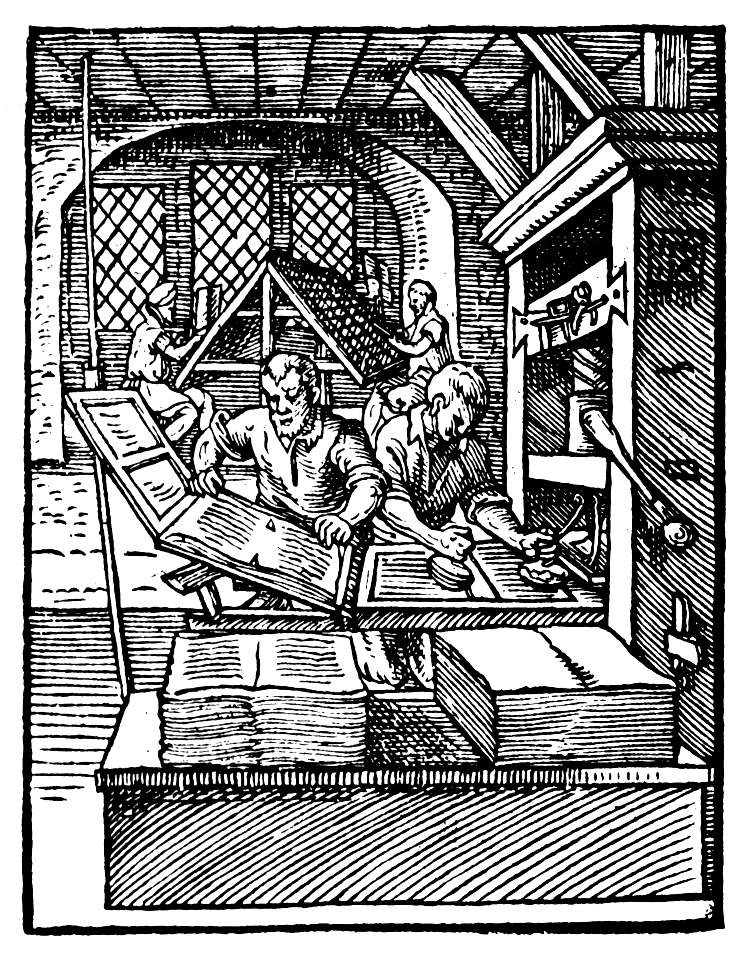

In about 1450, a man named Johannes Gutenberg who worked as a goldsmith in Germany combined some existing inventions into a brand-new one that would change the course of history. Using his knowledge of metals, Gutenberg perfected “movable type” (something that had already been invented in China). Movable type are little molds of letters and punctuation. They can be arranged in any combination on a rack and then inked for printing. In about 1450, Gutenberg combined movable type with a simple mechanical press—the same kind that was used to squeeze oil out of olives or juice out of grapes—to make a mechanical printing press. Working together, two or three printers could produce over 3,600 pages a day—a lot more than the few pages that a scribe could make copying by hand.

The first book produced with the new printing press was the Gutenberg Bible—and it was a sensation. People all over wanted copies. Within a few years, there were hundreds of print shops around Europe—and Italy was the printing capital of the world. Suddenly a book like The Decameron was available in thousands of copies. With the explosion of books came an explosion in literacy and education. More and more people were learning how to read, and more books were being written. The “light” that the early humanists dreamed of was glowing brighter and brighter.

The Renaissance version of a selfie, this is a print of an early print shop. This illustration from 1568 shows two printers working together on a Gutenberg-style press—the printer on the right is inking the type for the next pressing and the printer on the left is removing a freshly printed sheet. In the background, compositors are setting new pages of type on forms. (Image via Wikipedia)

It’s probably something you don’t think about. But the words you are reading right now are written in a “typeface.” The letters are produced in a particular style—and hopefully the typeface is easy to read. Tens of thousands of typefaces exist today, but they are all inventions that originated with the early movable type of the Renaissance. (Image via Wikipedia)

In addition to rediscovering and studying the writings of ancient Greeks and Romans, the humanists dug up archaeological sites to find artworks and learn about ancient Roman architecture. (This was surprisingly easy because they were living in the very cities that had once been the heart of the Roman Empire.) Soon painters and architects were reviving “classical” styles. Popular features of ancient Roman architecture, such as columns with capitals, rounded arches with a keystone on top, and large domes, were used in new buildings. Unlike the helter skelter cityscapes of the medieval period, Renaissance buildings were constructed symmetrically, with one side looking the same as the other.

This church and scuola in Venice, Italy, are named for San Rocco, the patron saint of plague victims. The scuola on the left was built in 1485. The rounded arches, fluted columns, and triangular pediments are typical of Renaissance architecture. (Odor Zsolt/ Shutterstock)

One of the largest churches in the world, St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome took over 100 years to build. The interior—with its columns, rounded arches and profound symmetry—shows the influence of Roman architecture on Renaissance design. (WDG Photo/ Shutterstock)

In Florence, the Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi was hired in 1418 to build a gigantic dome on top of the city’s cathedral. No one had built a dome that big since Ancient Rome, but Brunelleschi had studied how the dome of the ancient Roman Pantheon had been constructed—plus he had some new ideas of his own. One of Brunelleschi’s key inventions was building a supporting structure of circular rings and vertical ribs made out of stone, wood, and iron. Then, when masons began laying bricks to form the walls of the dome, Brunelleschi had them lay the bricks in a herringbone pattern. Using that pattern shifted the weight of the bricks toward the wooden supports. During the construction of Il Duomo, many residents of Florence feared the dome would collapse. But it didn’t—and to this day, Brunelleschi’s dome remains the largest masonry dome in the world.

Built in AD 126 (and still standing), the Pantheon in Rome was a temple to all of Rome’s gods. It is topped by an enormous concrete dome and was an inspiration to Renaissance architects. (Goran Bogicevic/ Shutterstock)

With its bell tower on one end and dome on the other, the cathedral of Florence, or Il Duomo di Firenze in Italian, is a mixture of medieval and Renaissance architecture. The dome, designed by the Renaissance architect Filippo Brunelleschi, is nearly 150 feet in diameter and weighs over 7 million pounds. It is considered a masterwork of architecture and engineering. (Baloncici/ Shutterstock)

Inside the dome of the cathedral of Florence, the Renaissance artists Giorgio Vasari, Federico Zuccari, and a team of assistants created this massive fresco of The Last Judgment. The final judgment was a common theme for artists decorating Renaissance churches. The artwork shows angels separating the good from the wicked. It is not considered one of the best artworks of the Renaissance, but it is definitely one of the biggest, about the size of eight football fields. (Samot/ Shutterstock)

Florence was the cradle of the Renaissance—and in the 1400s, it was the perfect place for new ideas to shine. Instead of being ruled by a king or a duchess, it was an independent city-state, ruled by members of the city’s trade guilds. There were guilds for lawyers, carpenters, bakers, doctors, leather workers, bankers, cloth makers, and more. Although leaders of the city were voted into office by the guilds, one family came to dominate the political scene: the Medicis. The Medici family had made their money in banking. Throughout the 1400s and part of the 1500s, they led the city of Florence and threw their financial support behind humanist art and architecture projects.

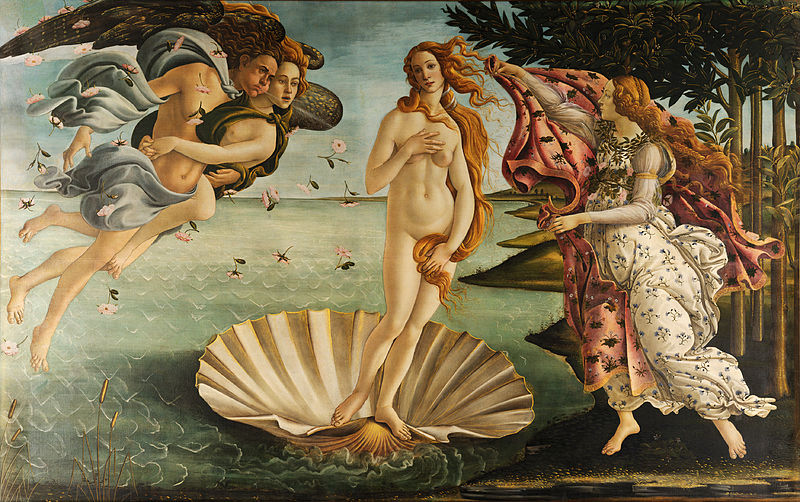

Humanist artwork is one of the most enduring features of the Renaissance. During medieval times, artwork had almost always been religious. And there was still a lot of religious artwork made for churches and chapels during the Renaissance. However, Renaissance artists also began painting and sculpting subjects inspired by Greek and Roman mythology, as well as portraits of real people.

In one of the most well-known paintings of the Renaissance, The Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli depicts the Roman goddess of love. To make Venus as sublime as possible, Botticelli added flecks of real gold to Venus’ hair. This painting was commissioned by the powerful Medici family in 1486. Like most Renaissance painters, Botticelli lived off commissions he received from wealthy patrons. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

The Medici family was a political dynasty that lasted for over 200 years, producing nine leaders of the Republic of Florence, four popes of the Catholic Church, and numerous dukes of Florence and Tuscany. This portrait of Ferdinando de’Medici as a youth was painted by Agnolo Bronzino in about 1560. Court painter to the Medicis for much of his career, Bronzino is known for the care he took in portraying his wealthy patrons’ costumes. In this painting, Ferdinando’s garment looks almost three-dimensional—as if you could feel the texture of the satin and velvet. Later in life, Ferdinando became the Grand Duke of Tuscany. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

Just as humanist writers wanted to use the language spoken by regular people, Renaissance artists wanted to show the world and its people as they really were. In older medieval European paintings—many of which were Christian-themed—subjects and figures are stylized and often stiff. Renaissance artists took pride in the realism of their work.

Here is one type of painting in which you can clearly see the change in styles: During both the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a common subject of religious paintings was Mary and the baby Jesus. In medieval paintings, Mary, Jesus, and various saints were often painted with gold halos, indicating that they were divine. During the Renaissance, the same religious subjects were painted to emphasize their human-ness.

This early medieval painting of Jesus and the abbot of a monastery dates from the 6th or 7th century. The artist of this beautiful piece is unknown. Note how the figures of Jesus and the abbot are stylized, almost like drawings from a cartoon strip. (Image via Wikipedia)

In this late medieval painting from 1308 in the Cathedral of Siena in Italy, the artist (Duccio di Buoninsegna) depicts Mary and the baby Jesus sitting on a throne surrounded by saints, angels, and apostles. Although it is still in the medieval style, it is moving toward a more realistic depiction of its subjects. (Image via Wikipedia)

Mary and the baby Jesus are depicted again here in this Renaissance masterpiece, the Sistine Madonna painted by Raphael in 1512. The work was commissioned by Pope Julius II for the monastery of San Sisto in Piancenza, Italy. Even though they appear in the clouds among otherworldly seraphs (look closely for faces peeking out of the mist), Raphael’s Mary and Jesus look far more lifelike than in medieval depictions. (Image via Wikipedia)

Two little angels? In this small section of the Sistine Madonna, two bored-looking cherubs wait for their elders to finish whatever it is they’re doing. (Image via Wikipedia)

How else did Renaissance artists make their work look more realistic? One huge development was the use of linear perspective. With linear perspective, painters could create a sense of depth and distance. Instead of looking flat, their paintings looked like they were in 3-D. Some artists got so good at it that they could use perspective to create optical illusions that fooled people into thinking that what they were seeing was real.

To understand linear perspective, imagine you’re standing on a railroad line, looking down the tracks into the distance. The farther away the tracks are, the narrower and smaller they look. Finally, you can’t see anymore and the tracks vanish into the horizon, where the land meets the sky. To make the tracks look real in a picture, you would need to create a horizon line, a vanishing point, and visual rays (called orthogonal lines) that converge on the vanishing point (just like the lines of the railroad track). To complete the sense of perspective, artists also used a technique called “foreshortening,” in which objects that are supposed to be in the distance are drawn smaller and smaller the farther away they are supposed to be.

Pietro Perugino painted this fresco in the Sistine Chapel in Rome in about 1481. Called The Delivery of the Keys, it shows Christ giving St. Peter the keys to heaven. It is a powerful example of linear perspective, with the edges of the paving stones on the plaza serving as orthogonal lines and narrowing to the vanishing point near the doorway of the temple. Note the foreshortening of the human figures at different points in the background. (Image via Wikipedia)

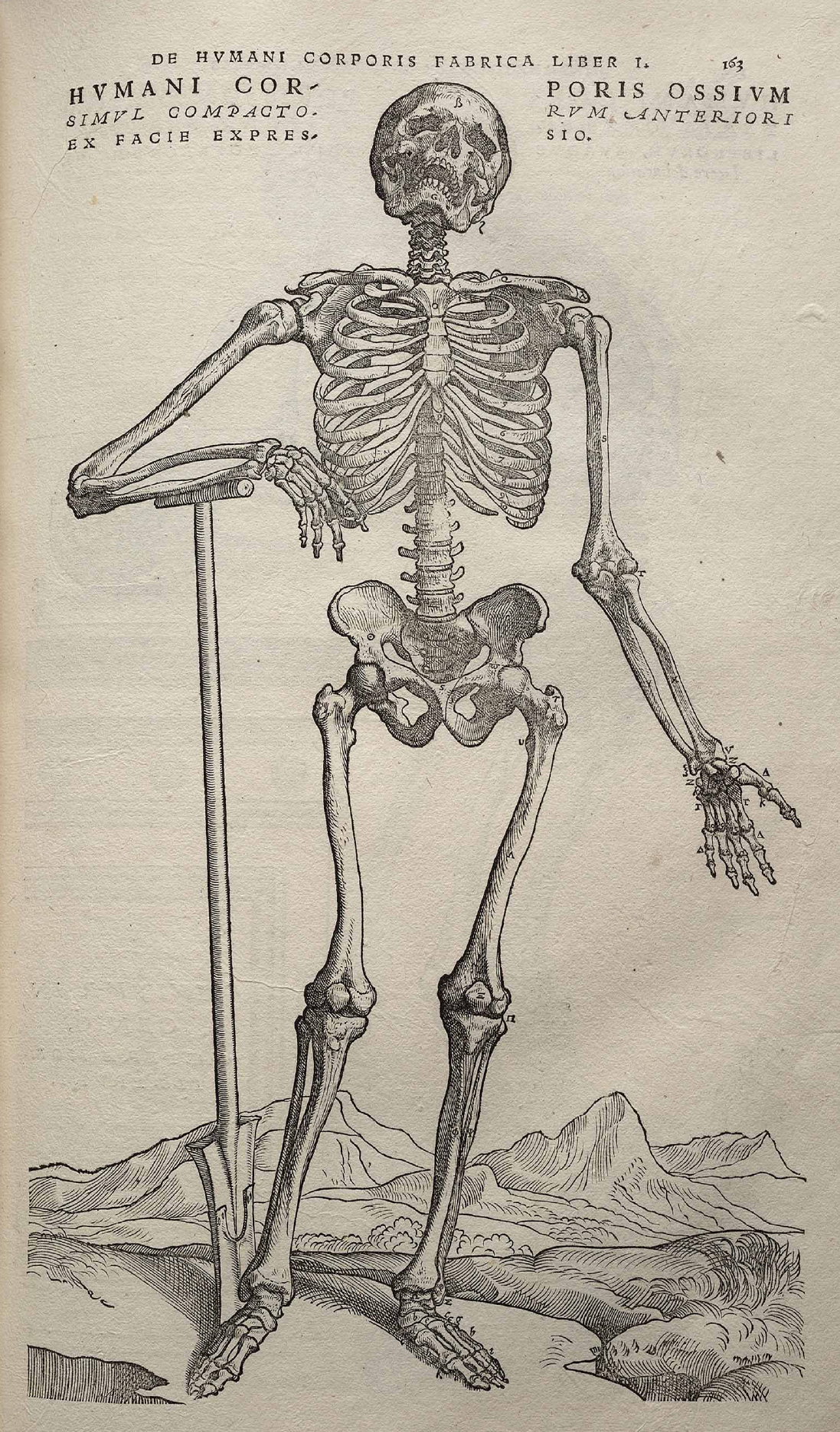

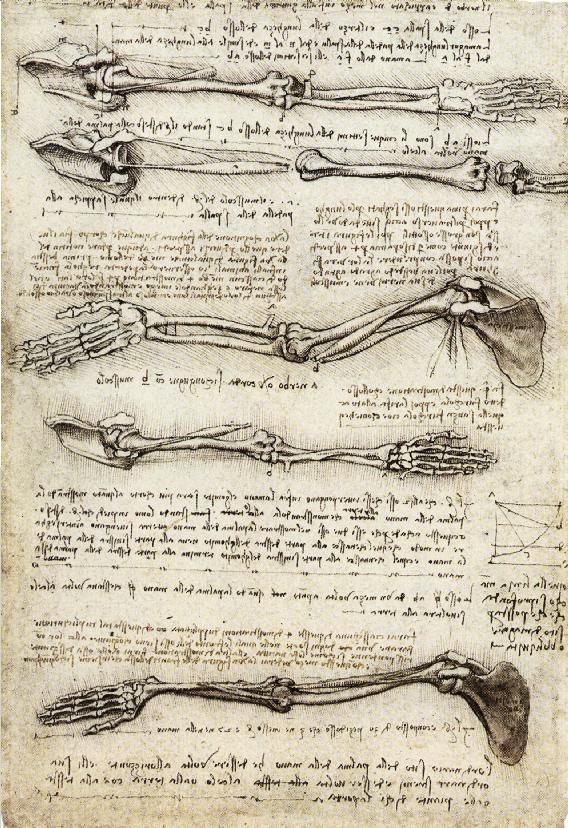

To depict the human form realistically was one of the goals of Renaissance artists. At the same time, Renaissance scientists wanted to learn more about human anatomy. This shared interest led to important collaborations between artists and physicians. In fact, two of the most famous artists of the Renaissance—Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo—teamed up with physicians to perform autopsies on dead bodies, so they could learn how muscles and body systems functioned and what lay beneath the human skin. In exchange, the artists demonstrated how to create accurate anatomical drawings so that what was learned from autopsies could be preserved, published, and shared.

One of the most important scientific books of the Renaissance was On the Fabric of Human Anatomy. Published in 1543, it was a seven-volume work by the physician Andreas Visalius and illustrated by one of the students of the great Renaissance painter Titian. Although the primary purpose of On the Fabric of Human Anatomy was to provide an accurate picture of human bones, muscles, and organs, it is filled with anatomical drawings set in odd places. This skeleton appears to be going on a hike in the Alps. (Image via Wikipedia)

Da Vinci took his anatomical studies further than any other artist, filling multiple sketchbooks with his drawings of the human body and pioneering the detailed documentation of dissections from multiple angles. (Image via Wikipedia)

Michelangelo, like most Renaissance artists, was fascinated by the human form. One of his most famous works is David. A 17-foot-high statue of the young shepherd who slayed the giant in the Bible story “David and Goliath,” David is sculpted in his birthday suit out of a massive block of white marble. The oversized form of David is both realistic and detailed, down to the bulging veins in the sculpture’s right hand and the tension in the right leg muscles, as if David is in motion and preparing to hurl a stone at an unseen giant. Commissioned by the leaders of Florence and completed in 1504, the statue of David the giant-killer became a symbol of the city’s independence and the liberty of its citizens.

Michelangelo chose to depict David in the moment before he slayed the giant. Meant to show that David was determined, courageous, and a bit fearful (as David would not know at this point if he would successfully defeat the giant), the marble forehead is tight with worry and concentration. (Image via Wikipedia)

One of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, Michelangelo was constantly in demand—and paid handsomely. But the work he did wasn’t just creative. It was backbreaking. When the pope asked him to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, Michelangelo spent four years standing all day on a scaffold with his neck craned back, while plaster plopped down on his face. The result is one of the most spectacular artworks of the Renaissance. Paintings of scenes from the Bible are framed in paintings of architectural features that look almost real. Angels are painted as if hanging from the rafters—and the whole ceiling appears multidimensional.

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was completed by Michelangelo in 1512. At a time before there were movies or even photographs, seeing these multidimensional scenes high above must have been overwhelming and even otherworldly. The far wall shows Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment, completed many years later in 1541. Frescoes along the other walls are by various Renaissance artists. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

One of Michelangelo’s fellow artists, Giorgio Vasari, wrote that after you had seen Michelangelo’s David, you never needed to look at any other sculpture. Vasari was equally thrilled by another Renaissance artwork from around 1506 that, to this day, is one of the most famous paintings in the world: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

Vasari wrote that the Mona Lisa was so lifelike that if you gazed at the painting long enough, you could see “the beating of the pulse.” Why was the Mona Lisa such a sensation? Why did Vasari say that it caused other painters to “tremble”? In a time before photography, computers, or copiers, Leonardo da Vinci perfected techniques that inspired other painters for hundreds of years to come. For example, instead of a distinct outline, everything in the painting is slightly “smoky” in an attempt to mimic natural light—something Leonardo had learned about in his scientific studies. The face of the Mona Lisa seems to naturally glow due to his microscopic layering of transparent paints. Instead of just foreshortening objects in the distance, Leonardo makes them blurrier as objects get farther away—just as they appear in real life.

Want to know a Renaissance secret? Leonardo worked on the Mona Lisa for years, but he never quite finished it to his own satisfaction. (Just don’t tell the 7 million visitors who go see the Mona Lisa in the Louvre Museum in Paris every year.) (Image via Wikipedia)

Written by Margaret Mittelbach.

[wp-simple-survey-29]